"Made in Japan" (1973) Album Description:

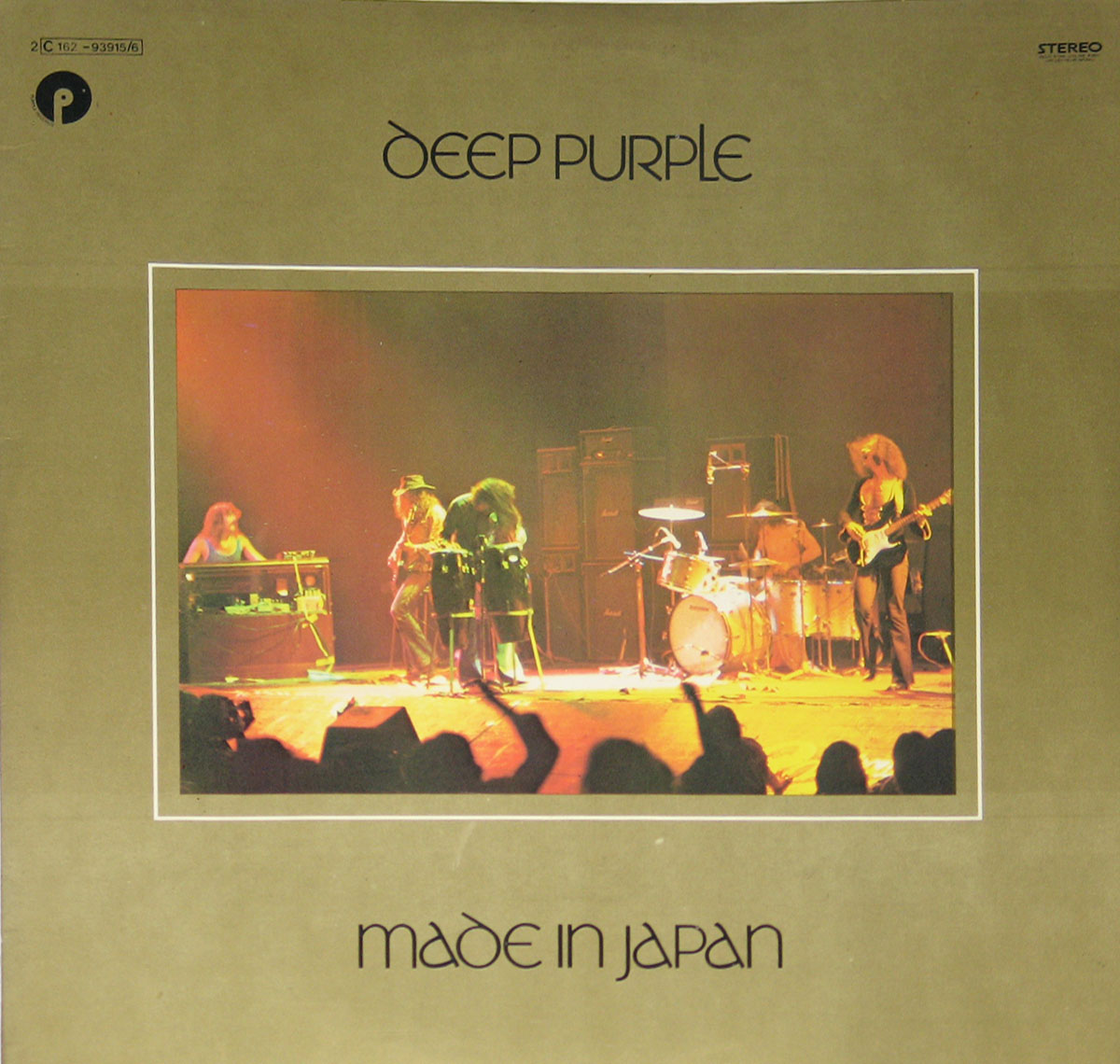

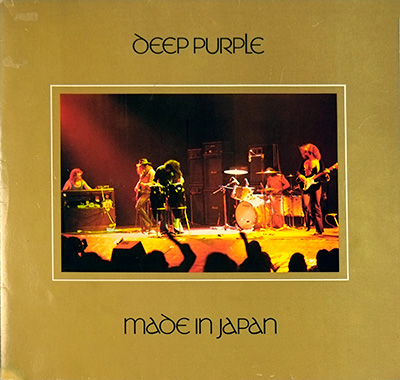

Deep Purple walked into Japan in August 1972 like a working band with a hit record and a deadline, then walked out with a double live album that sold like it had been waiting in everybody’s house already. It landed fast and loud, hitting the UK albums chart in early January 1973 and pushing up to No. 16, and when it finally rolled into the U.S. that spring it climbed to No. 6, which is not what happens to “special market” live souvenirs. The point is you can hear the band realizing, in real time, that the room is theirs; not politely, not gradually, but like someone turning a key and finding out the door was never locked.

England, 1972: the scene behaves badly on purpose

Back home, Britain in ’72 had this split personality: glam on the telly with the glitter and the smirk, prog stretching songs until they needed their own postal code, and hard rock getting heavier because nobody told it to stop. Deep Purple weren’t the scruffy outsiders anymore; they’d already done the big studio statement with "Machine Head" and they were touring like a machine that ate airports. A band at that pace doesn’t “decide” to make a live album so much as get cornered by reality: fans want proof, bootlegs are already doing the job badly, and the label would like something it can actually ship without calling it a “document.”

The weird part is how ordinary the setup is. Three nights, two cities, the kind of schedule that makes road cases smell like wet carpet and cigarette paper. But the crowd in Japan isn’t treating them like a foreign import; they’re singing back, tracking every move, and it changes the band’s posture. They play longer because they can. They take chances because the room won’t abandon them for it.

Where it sits, by contrast, not by sermon

Put it next to what else was moving in 1972 and you get the outline. Zeppelin had the big-boned swagger and the myth. Sabbath had the doom and the grim smile. Yes and Genesis were busy building mansions out of time signatures. Uriah Heep were flooding the stage with harmony and drama. Deep Purple, on this record, sound like the band that wants all of it and wants it now: riff weight, improvisation, speed, volume, and a sense that the song is just the starting gun.

- Led Zeppelin: loose power, blues as a weapon, the groove rolling downhill.

- Black Sabbath: slow heaviness, menace in the air, riffs like iron gates.

- Yes / Genesis: precision and architecture, songs that behave like novels.

- Uriah Heep: big harmonies, dramatic lift, choruses built to stick.

- The Who: live as impact, a band that hits you first and explains later.

The sound: attack, space, and the kind of tension you can taste

This is not a “nice” live recording. The guitars bite, the organ burns, the drums don’t pose for the microphone. You can feel the tempo as a physical thing: they push it, then they lean back, then they stomp on it again like they’re testing the floorboards. The air around the instruments isn’t clean; it’s crowded, hot, and moving.

"Highway Star" comes in like a throttle jammed forward, the band locked into that bright, fast churn where the riff is doing half the singing. "Child in Time" is the opposite kind of violence: it stretches, it swells, it threatens to fall apart, and then it doesn’t. "Smoke on the Water" is the blunt object everybody thinks they already know, but live it turns into a communal event, the riff less like a hook and more like a signal flare.

The secret isn’t just volume; it’s spacing. Jon Lord’s Hammond doesn’t sit behind the guitar, it argues with it, and sometimes it wins. Roger Glover’s bass is the calm hand on the steering wheel, even when the car is sliding. Ian Paice plays like he’s trying to keep the whole thing from levitating off the stage.

Then there’s Gillan. He’s not “frontman-ing” in the polite way; he’s acting out the lines, yanking them into shape, throwing screams like knives and then landing soft phrases like he suddenly remembered he’s allowed to breathe. If you ever wondered why this lineup felt like a single animal, this record answers without pausing to be helpful.

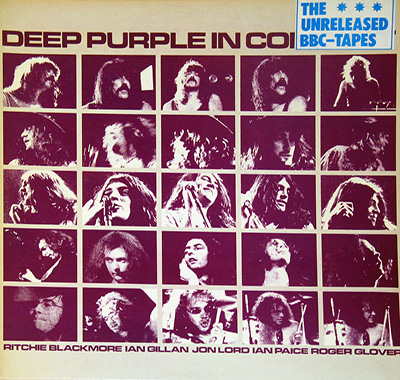

Key people, practical contributions

The sleeve tells you a lot if you listen to it like it’s gossip. The band take producer credit, which is a fancy way of saying they wanted control and they weren’t shy about it. Martin Birch is the quiet hero in the room, engineering the shows so the chaos survives the trip to tape without turning into mush. And when it came time to mix, it was Roger Glover and Ian Paice who showed up and did the actual work, which feels perfectly on brand for a band that’s always been half muscle and half stubbornness.

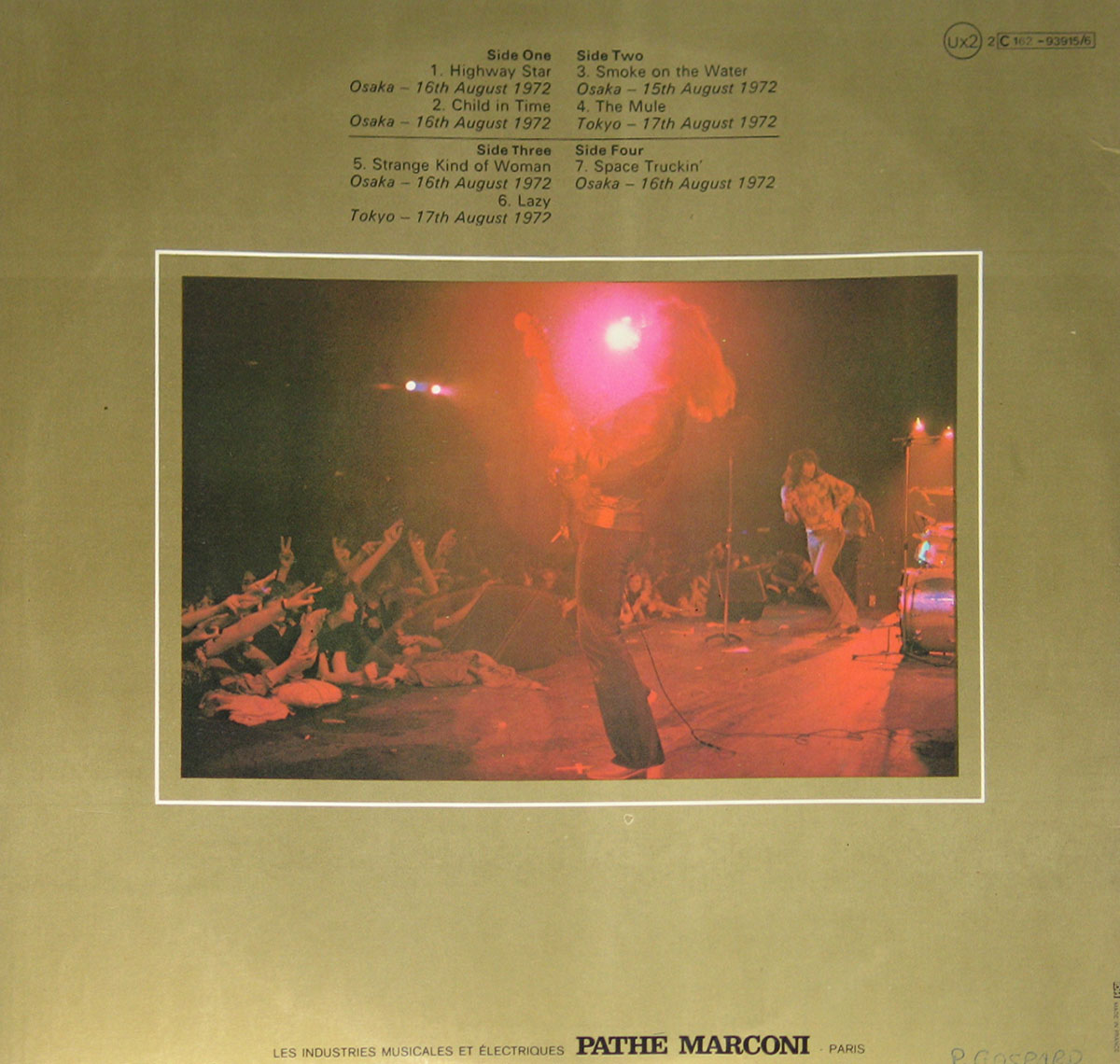

Fin Costello’s photography fits the whole situation: no romance, no velvet fog, just the band as a working unit in bright light. The gatefold isn’t trying to sell you fantasy; it sells you presence. If you want dragons, you’re in the wrong section of the record store.

The performances themselves are the real production choice. They leave the long stretches in. They let the band sound like it’s thinking out loud. That takes confidence, or exhaustion, or both.

Band chemistry as cause-and-effect, not a timeline

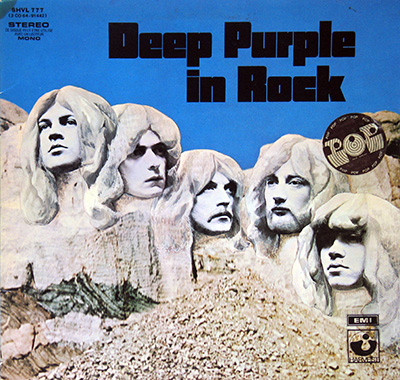

Mark II exists because Deep Purple got tired of being a clever British band and decided they wanted to be a dangerous one. Swapping in Ian Gillan and Roger Glover in 1969 didn’t just change the vocals and bass; it gave Blackmore and Lord a front line that could take the heat when the music got bigger. By 1972 they’re touring constantly, and the live show becomes the place they can stretch without the studio clock tapping its foot.

But the same intensity that makes this record crackle is also the thing that grinds people down. The band are coming off a relentless run, and you can hear the pressure in how hard they play: not sloppy, not careless, but urgent, like they’re trying to outrun tomorrow’s argument. A few months later the Mark II lineup is basically running on fumes, and by mid-1973 Gillan is out, with Glover following, and the whole machine has to rebuild itself.

That’s the uncomfortable truth: a band doesn’t sound this alive because it’s comfortable. It sounds this alive because it can’t sit still.

Controversy, or the myths people use instead

There isn’t a clean, headline-grabbing scandal attached to "Made in Japan" the way some albums arrive with police reports and broken TV cameras. The mess here is quieter and more industry-shaped: bootlegs were already circulating, and the band had been publicly irritated by the whole bootleg economy; part of the logic of doing an official live set was to cut that market off at the knees. The other half of the story is that the band initially treated the live album like a Japan-only obligation, and it escaped anyway, because commerce loves a good escape artist.

The misconception people cling to is that the band “didn’t care” about the record, like that cancels what you’re hearing. Sure, they downplayed it, and the accounts around the mixing sessions read like a band too tired to pretend they’re having fun. None of that changes the fact that the tape caught them at full voltage. Intent is cheap; sound is expensive.

One quiet personal anchor

I remember hearing "Smoke on the Water" late at night on the radio and recognizing the crowd noise before I recognized the riff, which felt backwards and completely right. The next day the record shop had that double album sitting there like a dare, and people were already arguing about which side was “the good one.”

What the record actually does, track by track, without reciting the menu

If you want the short version: the band take familiar songs and treat them like rooms they can rearrange. They speed up the corners. They widen the hallways. They let solos breathe long enough to become scenes instead of decorations.

- "Highway Star": speed with purpose, the band snapping into a fast, bright grind that feels like a countdown.

- "Child in Time": tension as structure; the quiet parts aren’t rest, they’re suspense.

- "Smoke on the Water": a riff turned into a chant, with the band stretching the middle like they’re testing how far the crowd will follow.

- "Space Truckin'": less a song than a controlled demolition, the kind where you’re not sure the building will fall the way they drew it up.

External references and further reading

- Wikipedia: Made in Japan (release dates, recording dates, personnel)

- Official Charts (UK): Made in Japan chart run

- The Highway Star: Discography notes (engineering/mixing credits)

- Deep Purple Official Store: Made in Japan Super Deluxe (concert dates/context)

- Wikipedia: Who Do We Think We Are (band fatigue and Mark II endpoint context)

.jpg)