The year is 1969. The Summer of Love has withered, replaced by a cynical hangover. Nixon's in the White House, the Manson Family's on a killing spree, and the Vietnam War rages on. Rock music is in a state of flux, with psychedelia fading and heavier sounds emerging. Into this chaotic landscape strides Deep Purple, a band struggling to find their footing with their self-titled third album, ominously dubbed "Deep Purple III" by fans.

This is the sound of a band on the brink. The original Mk. I lineup – Rod Evans' affected vocals, Ritchie Blackmore's neoclassical guitar heroics, Jon Lord's swirling organ, Nick Simper's plodding bass, and Ian Paice's thunderous drums – is about to implode. And it shows.

"Deep Purple III" is a sonic mishmash, a hodgepodge of styles that never quite gels. It veers from the faux-Baroque opener "Chasing Shadows" to the bluesy stomp of "Blind" to the psychedelic meanderings of "Lalena." There are moments of brilliance – Blackmore's furious fretwork on "The Painter," Lord's haunting organ on "Fault Line" – but they're fleeting.

The album was recorded at De Lane Lea Studios in London, with producer Derek Lawrence at the helm. Lawrence, known for his work with the Moody Blues, tries to impose a pop sensibility on the band, but it doesn't quite fit. The production is muddy, the mix uneven, and the songs feel disjointed. The album also marks a turning point in the band's songwriting approach, moving away from covers and towards entirely original material.

Historically, "Deep Purple III" is significant for a few reasons. It marks the end of the band's early, more experimental phase and the beginning of their transition to the heavier sound they would become known for. It's also a testament to the growing influence of Blackmore as a songwriter, with his compositions becoming more prominent.

The album is noteworthy for several fan-favorite tracks. "Chasing Shadows" stands out for its dark atmosphere and unique structure, "Blind" features a raw blues-rock energy, and "Lalena," a Donovan cover, is often praised for its psychedelic charm. The instrumental "April" is a sprawling, multi-part epic showcasing the band's musical diversity and ambition.

But in the moment, "Deep Purple III" was a critical and commercial disappointment. It failed to chart in the UK and received lukewarm reviews. Critics slammed Evans' vocals, the band's lack of focus, and the album's overall unevenness. The subsequent departure of Evans and Simper, replaced by Ian Gillan and Roger Glover, signaled a radical shift in the band's trajectory.

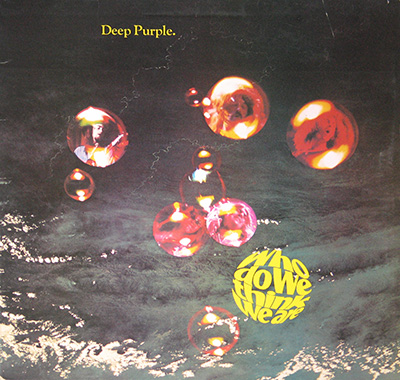

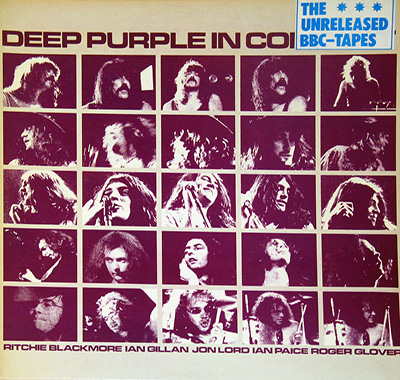

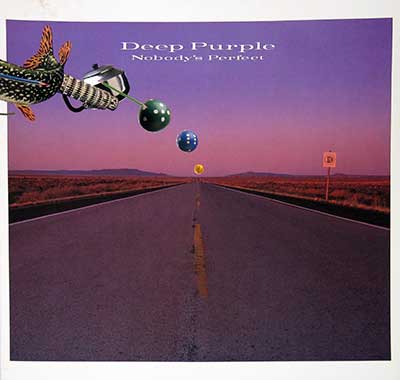

The controversy surrounding the album only added to its troubled legacy. The cover art, featuring a bizarre collage of band members' faces, was deemed "ugly" and "off-putting." And the decision to omit the band's name from the front cover further alienated fans.

Listening to "Deep Purple III" now, it's easy to hear why it failed to connect. It's a transitional album, a bridge between the band's psychedelic past and their hard rock future. It's a record that's neither fish nor fowl, caught in a stylistic no man's land.

But for all its flaws, "Deep Purple III" is a fascinating artifact. It's a snapshot of a band in turmoil, struggling to find their voice amidst a rapidly changing musical landscape. It's a testament to their resilience that they were able to overcome these early setbacks and go on to achieve global success.

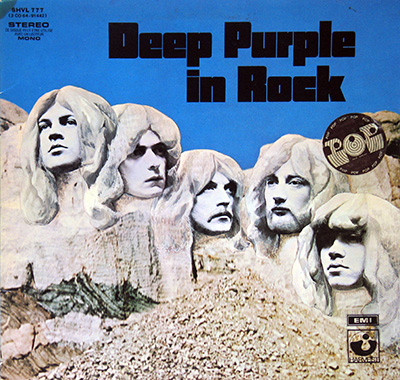

So, is "Deep Purple III" a lost classic or a forgotten footnote? It's hard to say. But it's worth revisiting, if only to appreciate how far the band had come by the time they released their groundbreaking fourth album, "Deep Purple in Rock." That's when they finally found their true calling, leaving behind the psychedelic haze and embracing the heavy metal thunder that would define their legacy.

-Large.jpg)

-9056.jpg)

-9057.jpg)

-label.jpg)

-9058.jpg)

-9059.jpg)

.jpg)