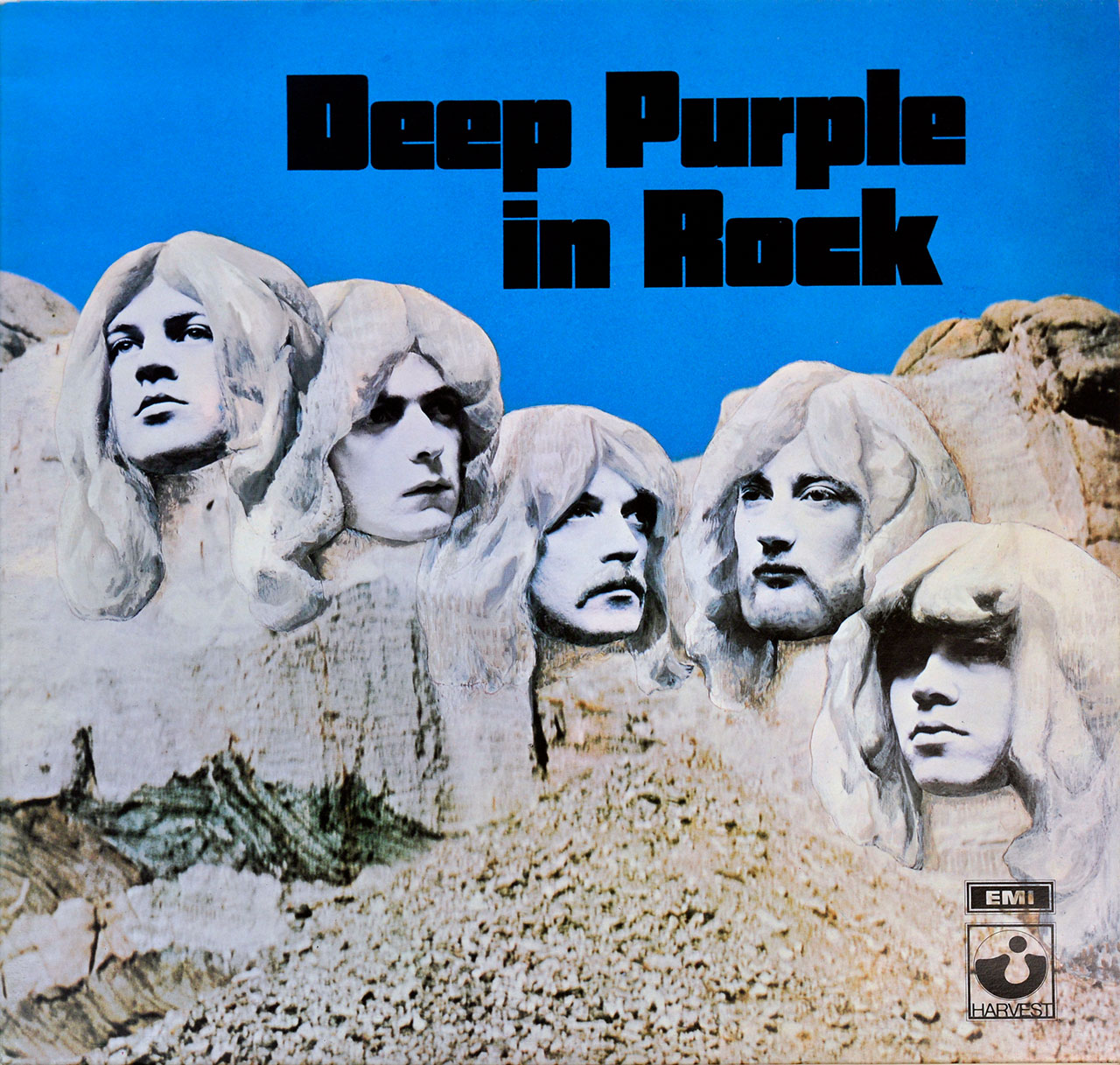

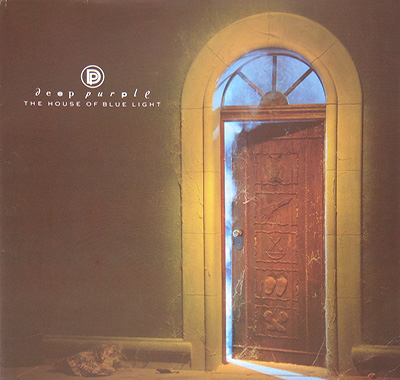

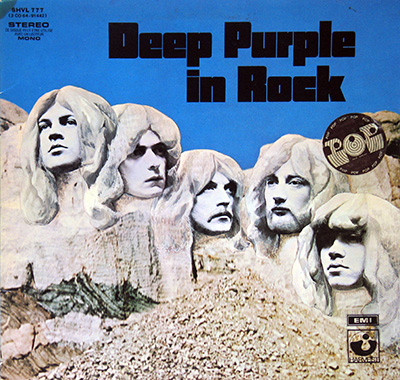

"In Rock" (1970) Album Description:

Deep Purple walked into 1970 and made a very specific promise on "In Rock": the songs would be loud, the band would sound like one animal, and nobody would apologize for any of it. This is the record where the riffs stop flirting and start throwing furniture, the organ quits behaving like decoration, and the vocals climb so high they feel borderline irresponsible. The funny part is how controlled it all is beneath the noise, like the band learned the rules just long enough to break them efficiently.

England, 1970: the air felt tense, so the amps got bigger

Britain didn’t drift into 1970 on a flower-scented breeze; it lurched. A general election lands in June and suddenly the country’s mood looks even more divided than the pub conversations made it sound. Add the background hum of Cold War anxiety, and you get a culture that’s jittery, a little impatient, and weirdly hungry for something that feels decisive. "In Rock" doesn’t “reflect” that so much as it barrels through it, like a band trying to out-shout the headlines.

Hard rock at the time still had one foot in blues manners and one foot in psychedelic sprawl. This album puts both feet on the stage edge and leans forward. The message isn’t subtle: crank it, tighten it, hit harder, and keep going until somebody complains.

The line-up shift that actually mattered

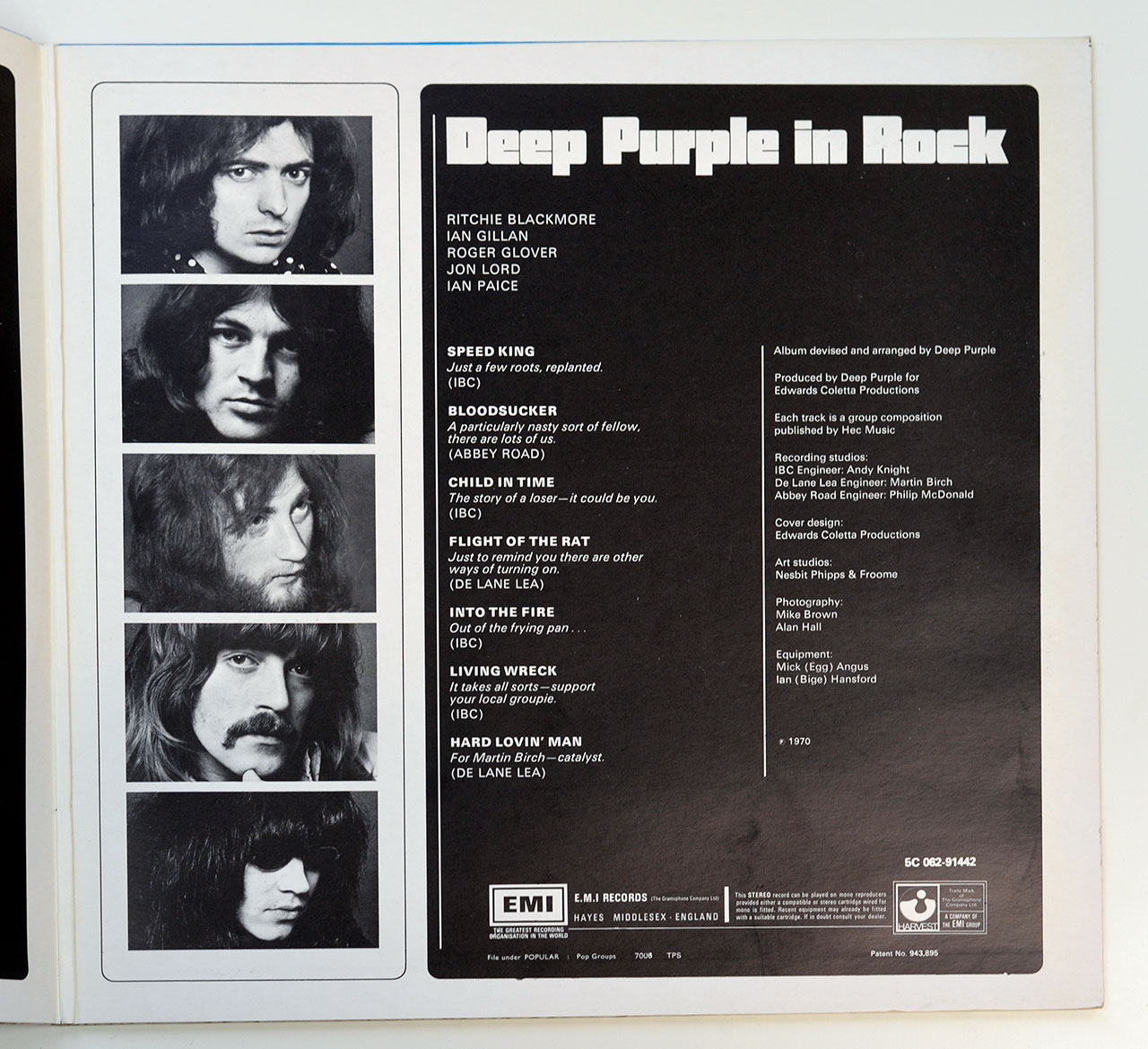

The cause-and-effect story is simple and brutal: a new singer and bassist show up, and suddenly the band sounds like it has a spine. Ian Gillan brings that sharp, theatrical bite, but he doesn’t sing like a polite frontman; he sings like he’s trying to tear a hole in the ceiling and see who flinches first. Roger Glover’s bass doesn’t just follow the guitar, it anchors the whole thing so the band can speed up without turning into a bar fight.

The rest of the machine is already dangerous. Ritchie Blackmore’s guitar has that clipped, surgical attack that turns even quick runs into threats. Jon Lord’s Hammond isn’t “warm,” it’s abrasive and overdriven, like a factory siren learned how to play chords. Ian Paice plays with swing in his bones, but he hits like he’s late for something.

How it sounds when the band stops being polite

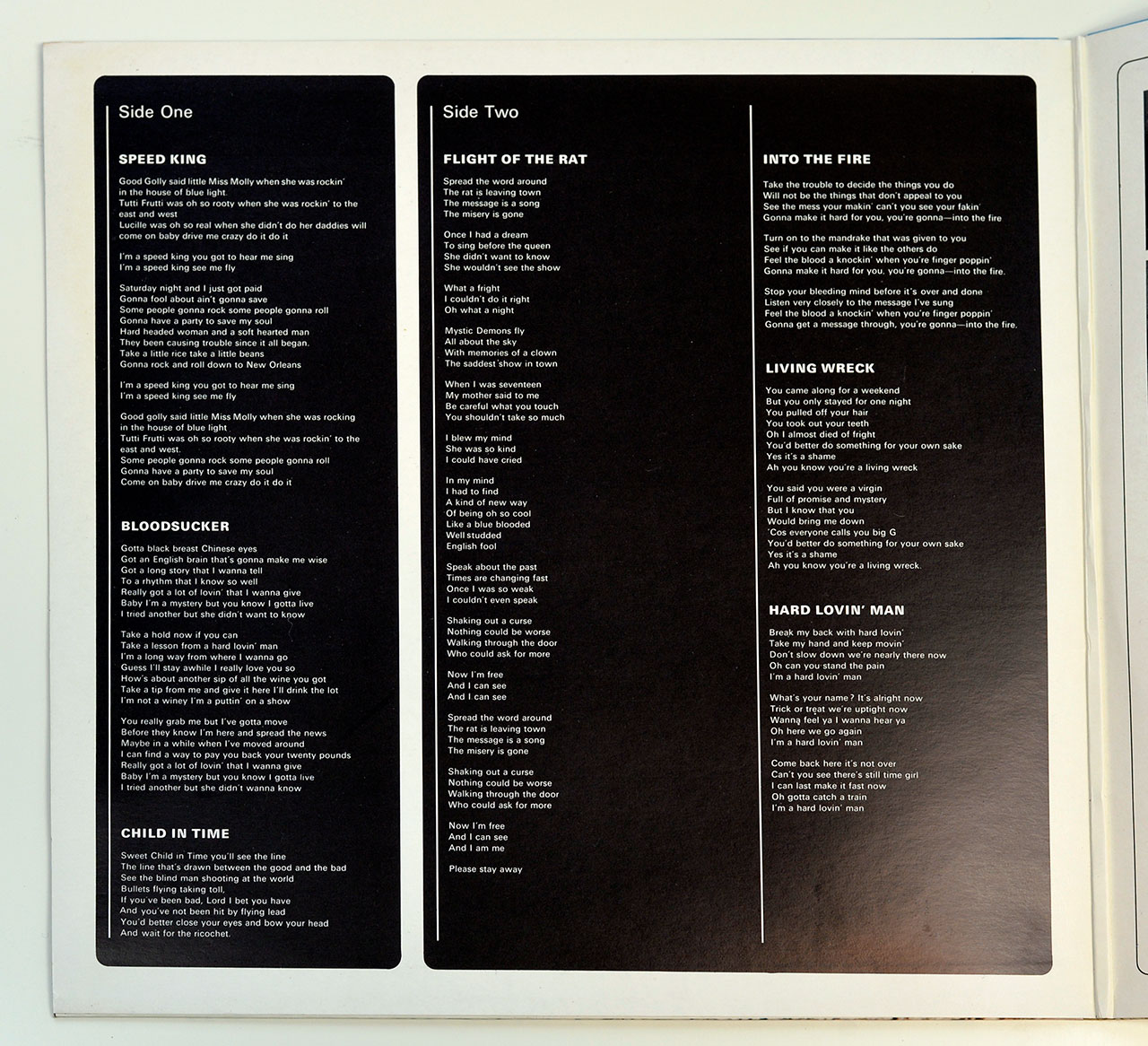

"Speed King" opens like somebody kicked open a studio door and yelled “roll tape.” The tempo feels impatient, the breaks snap back into place, and the whole thing has that sweaty, live-wire push where you can almost hear the room getting smaller. The guitar and organ don’t share space so much as wrestle for it, and the rhythm section keeps the fight from turning sloppy.

"Into the Fire" has the blunt shove of a club PA that’s a little too hot: thick riff, tight pulses, no scenic detours. Then there’s "Child in Time" stretching the room wide, building from tense quiet to a long, escalating pressure that ends up sounding like a warning siren with a melody. It’s the one moment where the album lets the air in, and it uses that air to scare you.

Peer pressure: who else was roaring that year

The scene in 1970 was crowded with bands who all wanted the crown, but they wanted different crowns. Led Zeppelin had the swaggering blues heft and the supernatural thump. Black Sabbath were pushing doom and dread like a new religion. The Who could turn volume into a narrative weapon, while Free kept a stripped, heavy groove that felt human and bruised. Bands like Uriah Heep were also starting to lean into big melodrama and thickened sound, but "In Rock" doesn’t wait for anyone to catch up.

What separates Purple here is the sheer density of the attack: the organ is a lead weapon, the guitar is all edges, and the vocals refuse to behave. It’s not “heavier” in some abstract scoring system. It’s more confrontational, more compressed, more willing to sound like the band might break something on purpose.

Behind the glass: who did what, practically

The production credit is the band themselves, and that matters because it explains the attitude: no smoothing, no soft lighting, no asking permission. The recording trail runs through London rooms that each leave fingerprints. IBC Studios captures the punch and directness, the sense of “get the take and move.” De Lane Lea brings that pressured, workmanlike grit where the sound feels pushed. Abbey Road shows up like a disciplined finishing move, tightening edges without neutering the threat.

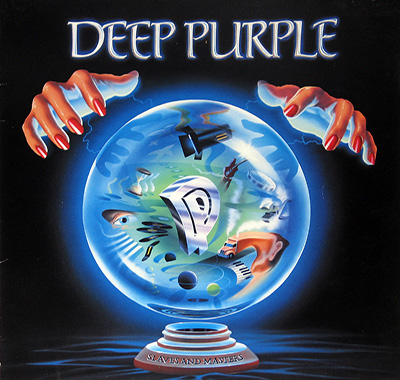

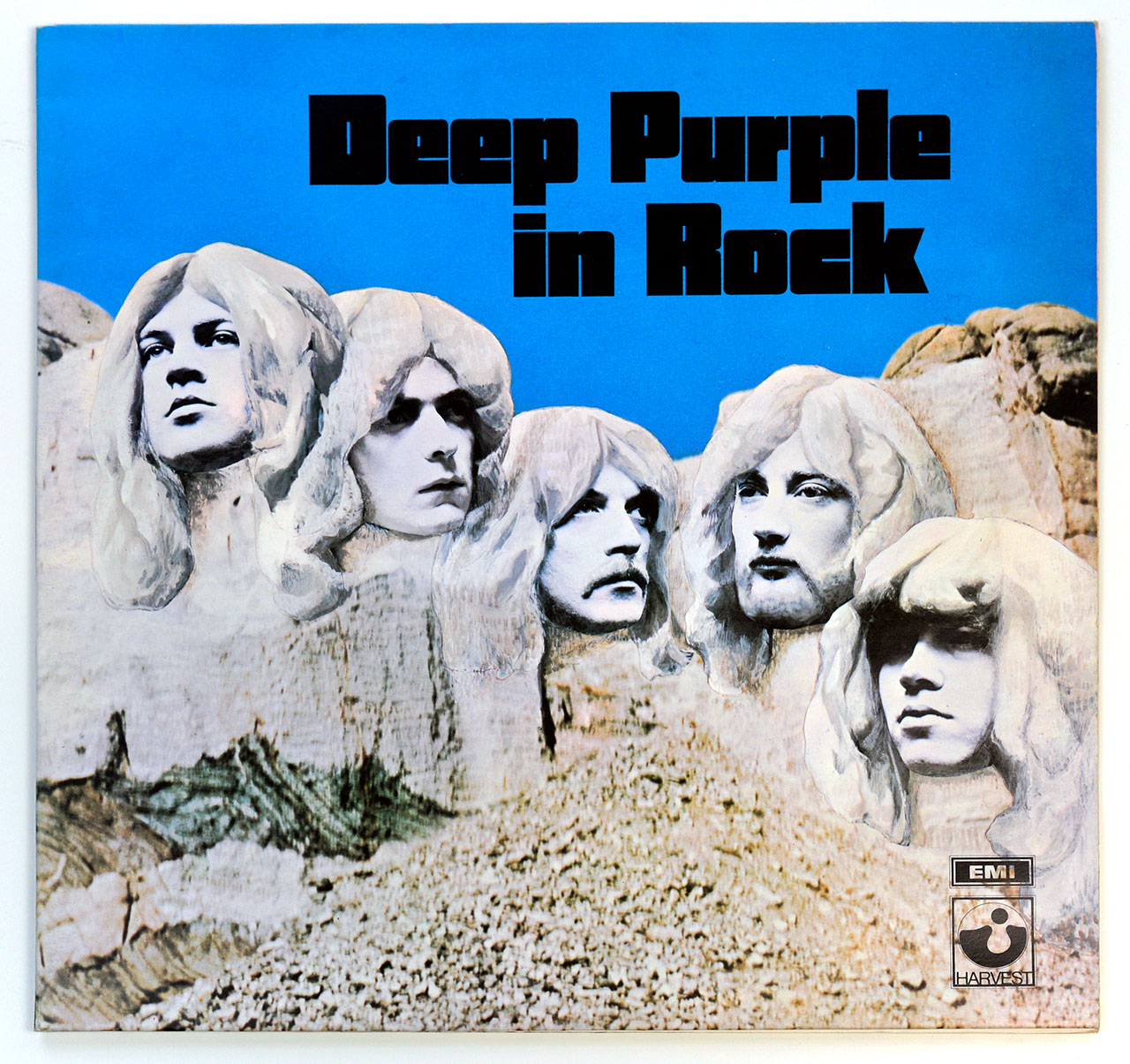

Engineers get named in a way that reads like a map: Andy Knight attached to IBC, Martin Birch tied to De Lane Lea, Philip McDonald linked with Abbey Road. This is the practical stuff that decides whether the record hits you in the chest or just makes a nice noise in the background. The cover side of the operation is similarly no-nonsense: Edwards Coletta Productions handling cover design and production, Nesbit Phipps & Froome executing the art studio work, and photos credited to Mike Brown and Alan Hall. Nothing mystical here, just people doing the job and leaving evidence.

A quick listening map for the impatient

- Need immediate impact: "Speed King" then "Into the Fire".

- Want the long pressure build: "Child in Time".

- Prefer the nastier corners: "Bloodsucker" and "Hard Lovin’ Man".

Controversy: not a scandal, just a recurring argument

There wasn’t a big public meltdown attached to this release, no courtroom circus, no dramatic banning. The messier story is smaller and more interesting: the organ figure at the heart of "Child in Time" traces back to a 1969 track called "Bombay Calling" by It’s a Beautiful Day, and the borrowing didn’t exactly stay one-way. People still argue about it like it happened yesterday, mostly because rock fans love a theft story almost as much as they love a riff.

The bigger misconception is the lazy one: that "In Rock" is only about volume. The volume is real, sure, but the real trick is the discipline underneath it. This band is controlling the chaos, not drowning in it, and that’s why the record still hits like a shove instead of a nostalgia piece.

One quiet anchor, because records don’t live in museums

Late-night radio, low volume at first so nobody wakes up, then the chorus hits and the hand reaches for the knob anyway. That’s how this album sneaks into your habits: not by asking nicely, but by daring you to keep it quiet.

References

- Deep Purple in Rock (album overview, release and recording info)

- "Child in Time" (song background and source riff note)

- UK Prime Minister history: Edward Heath (context for 1970 political shift)

- 1970 United Kingdom general election (timing and outcome)

- Discogs master entry (credits and release variants cross-check)

- MusicBrainz release group (structured credit and release data)

.jpg)