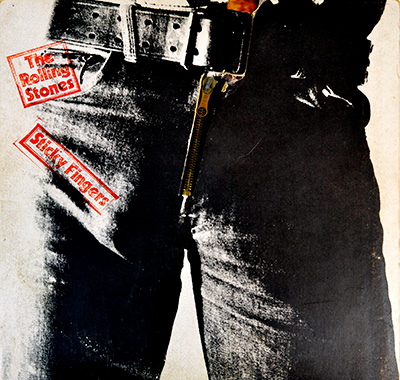

Rolling Stones – “Sticky Fingers” Re‑issue: Heat, Haze, and a New Label’s Bite Album Description:

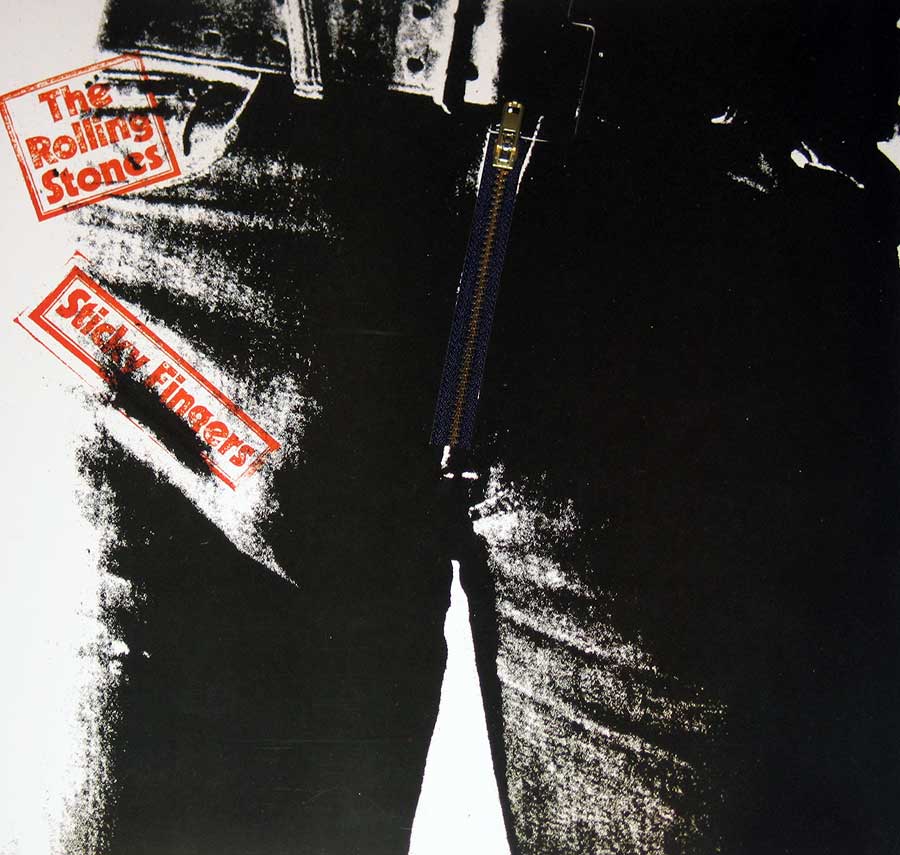

By the early seventies the British blues engine had traded its chrome for scar tissue. With “Sticky Fingers”, the Rolling Stones opened the door to that decade with a record that sounded like sweat drying on denim. This re‑issue brings the album back with mass and intent—heavy vinyl, restored packaging, a zipper that still threatens your shelving—while letting the music breathe with a wider, more deliberate stride.

1971: A Band Changes Address and Attitude

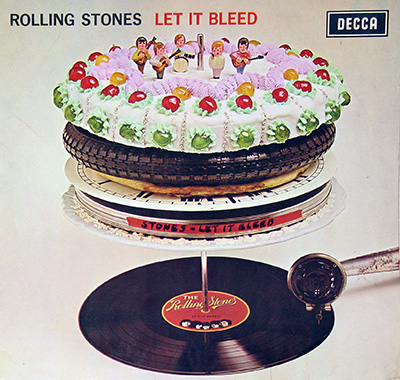

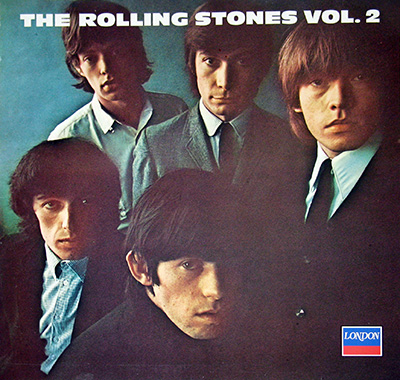

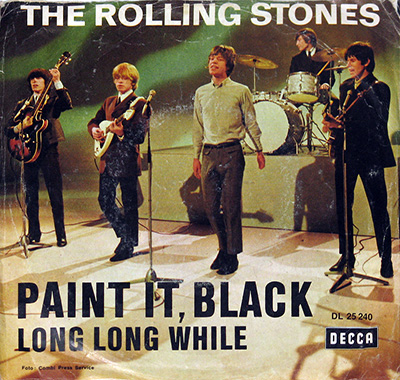

Released in April 1971, the album arrived as the Stones closed out their Decca/London chapter and rolled out their own imprint, Rolling Stones Records. The move wasn’t just corporate reshuffling; it was a creative declaration. The band had weathered the loss of Brian Jones in 1969 and folded Mick Taylor fully into the lineup. Taylor’s lyrical guitar lines reframed the rhythm section’s punch and gave Keith Richards a partner for the kind of interlocking parts that feel tossed-off until you try to play them.

Studios That Smell Like the Songs

This record is a miles‑long postcard stamped in multiple rooms. In London, Olympic and Trident Studios captured the band’s nocturnal glide. Down in Alabama, Muscle Shoals Sound Studio added humidity you can practically taste. You hear that Southern air in the drag of the groove—especially when the guitars lean back and the rhythm section keeps its shoulders squared. The contrast is the point: London precision against Muscle Shoals humidity, the push‑pull that makes these tracks walk with a crooked grin.

Jimmy Miller’s Tough Love

Producer Jimmy Miller had the Stones at a peak of concentration. He didn’t polish away the grime; he put a frame around it. Tempos sit where the song lives, not where a metronome says they should. Horns appear like streetlights in drizzle. Acoustic guitars stand up straight next to electric ones. The mix grants space to percussion tics and room tone, letting the band’s timing—never perfect, always human—be the hook you didn’t see coming.

Musical Exploration: Swagger with Shadows

There’s the obvious strut: the opener bites down with a riff that sounds carved from railway steel, a rhythm section marching with a dancer’s balance. The ballads don’t beg; they confess, and they do it in rooms where the air doesn’t move. When the guitars lock into an extended workout, it’s not a soloist’s monologue but a conversation—Mick Taylor speaking in long sentences, Richards tossing in the barbed asides. Even the country sway isn’t pastiche; it’s the Stones translating American vernacular into their own midnight language.

Band History Woven Into the Arrangements

Post‑’69, the group plays like a unit that has learned to leave space for danger. Charlie Watts lays down drum parts that understate until the exact second understatement becomes tension. Bill Wyman centers the tunes with lines that move more than they appear to. Jagger is at a vocal cusp here—still the London club prowler, already the arena narrator. And Taylor, on his first full album with the band, signs his name in vibrato and sustain rather than flash.

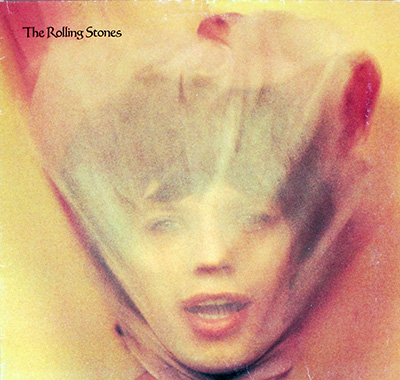

Controversies: What the Songs Say and What the Cover Does

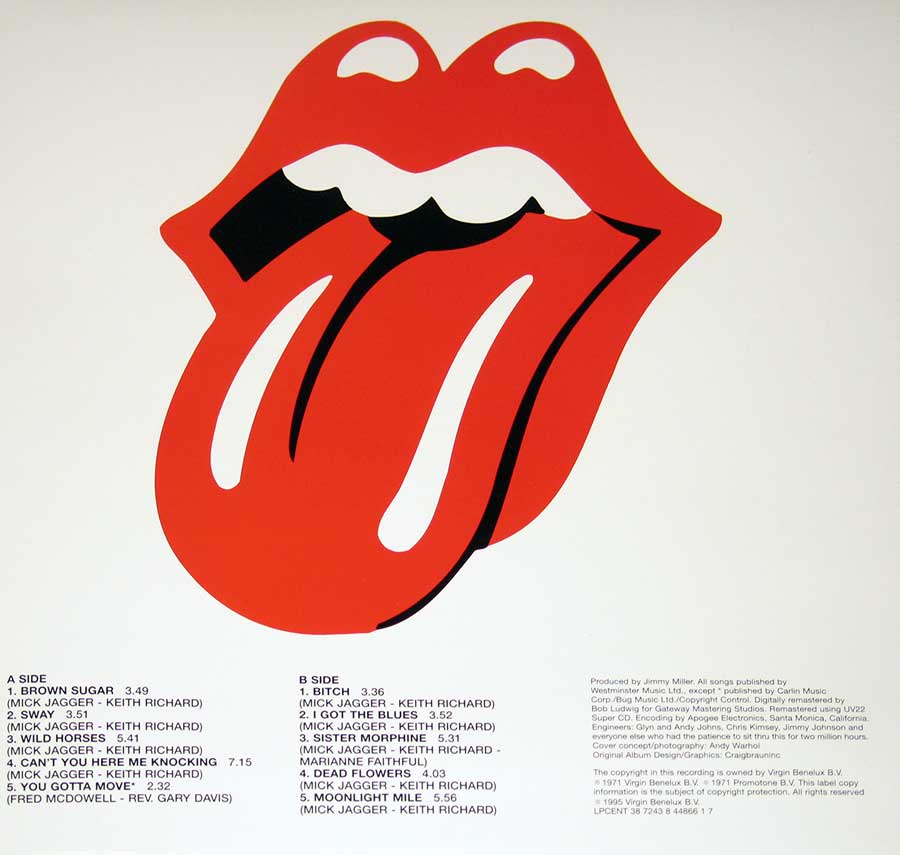

The lyrical content on the lead single drew heat then and now—provocation baked into melody. The album jacket added its own scandal. The working zipper was more than a gimmick; it was Pop Art turned into packaging, a wink with teeth. Some retailers complained the hardware scuffed adjacent sleeves; Spain banned the original image entirely. Inside the track list, authorship debates simmered—most notably over “Sister Morphine” and Marianne Faithfull’s contribution—reminding listeners that creative chemistry often leaves a paper trail as tangled as the music feels inevitable.

Art & Identity: Warhol, Braun, and the Tongue That Spoke

Andy Warhol’s concept, executed with design by Craig Braun, turned the jacket into an object you handle, not just see. The inner materials showcased the newly minted tongue-and-lips emblem, a John Pasche design that said more about the band’s brand of appetite than any press release. This was how rock looked when it meant business: loud, tactile, and almost illegally direct.

The 1990s Re‑issue: Mass, Mastery, and Memory

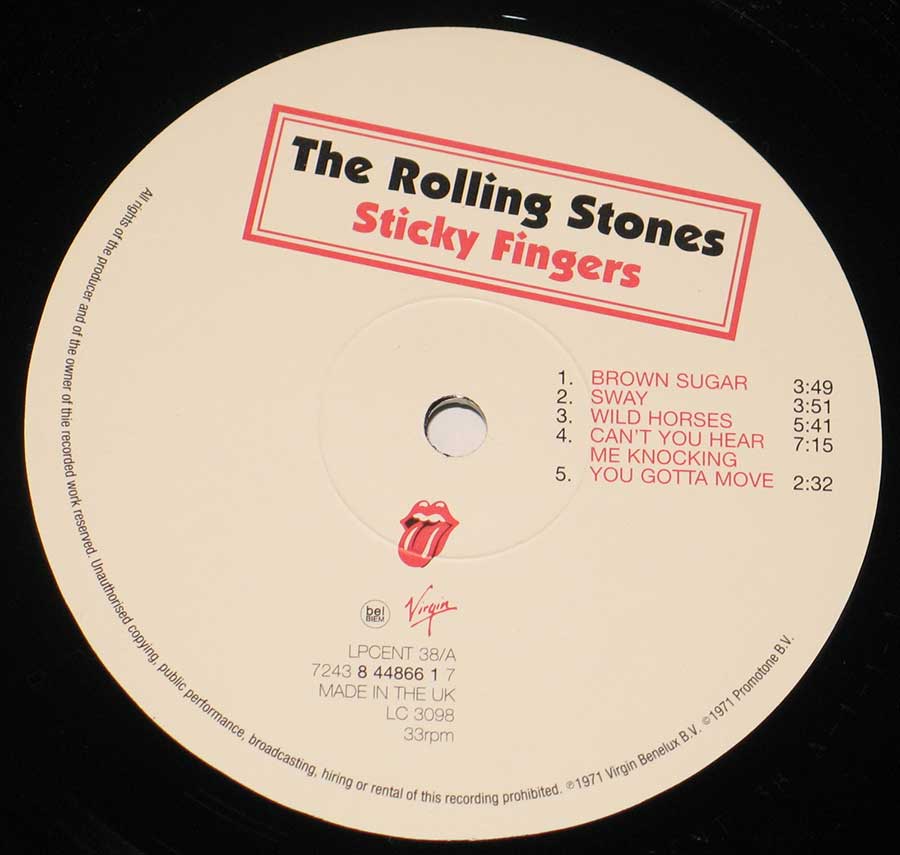

This UK re‑issue arrives on substantial 190‑gram vinyl and reflects the early‑’90s restoration push that treated the Stones’ catalog like film negatives in a temperature‑controlled vault. The mastering presents transients with extra air—acoustic guitars have wood in their knock; cymbals decay into black rather than gray. The bass doesn’t just thump; it locates the room. You can follow the tambourine’s tilt, the piano’s felt, the smallest changes in Richards’ right‑hand attack. Packaging respects the original mischief: the zipper functions, the inner sleeve signals the band’s self‑owned era, and credits align with a modern accounting of who did what.

Track‑Level Moments Worth Your Ears

“Brown Sugar” opens like a door kicked in—horn stabs and guitar chug placed just behind the beat, the groove elastic but unbreakable. “Sway” leans on late‑night strings and a bass figure that smokes rather than sprints. “Wild Horses” is restraint as arrangement, harmonies hovering like breath on cold glass. The long mid‑album workout lets the guitars argue into agreement, while “You Gotta Move” returns the band to the Delta with a Muscle Shoals hush. Flip the record and “Bitch” throws elbows—riffs braided with brass—before “I Got the Blues” uses organ swells and held notes to make time itself wobble. “Sister Morphine” is a whispered cliff‑edge. “Dead Flowers” grins through barroom neon. “Moonlight Mile” shuts the door gently behind you with strings that feel like headlights disappearing over a hill.

Why This Re‑issue Matters Musically

The appeal isn’t nostalgia; it’s focus. On a clean, heavy pressing, the album’s internal logic reveals itself—the way grooves expand and contract, the micro‑hesitations that give choruses their lift, the hand‑played geometry between Watts’ ride and Richards’ rhythm. The re‑issue doesn’t modernize the record; it clarifies the argument the Stones were making in 1971: that rock could be both filthy and meticulous, American and English, studio‑crafted and sleight‑of‑hand live.