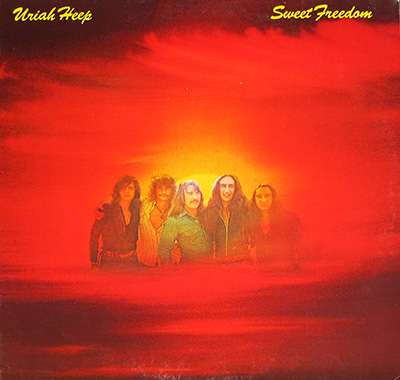

"Sweet Freedom" Album Description:

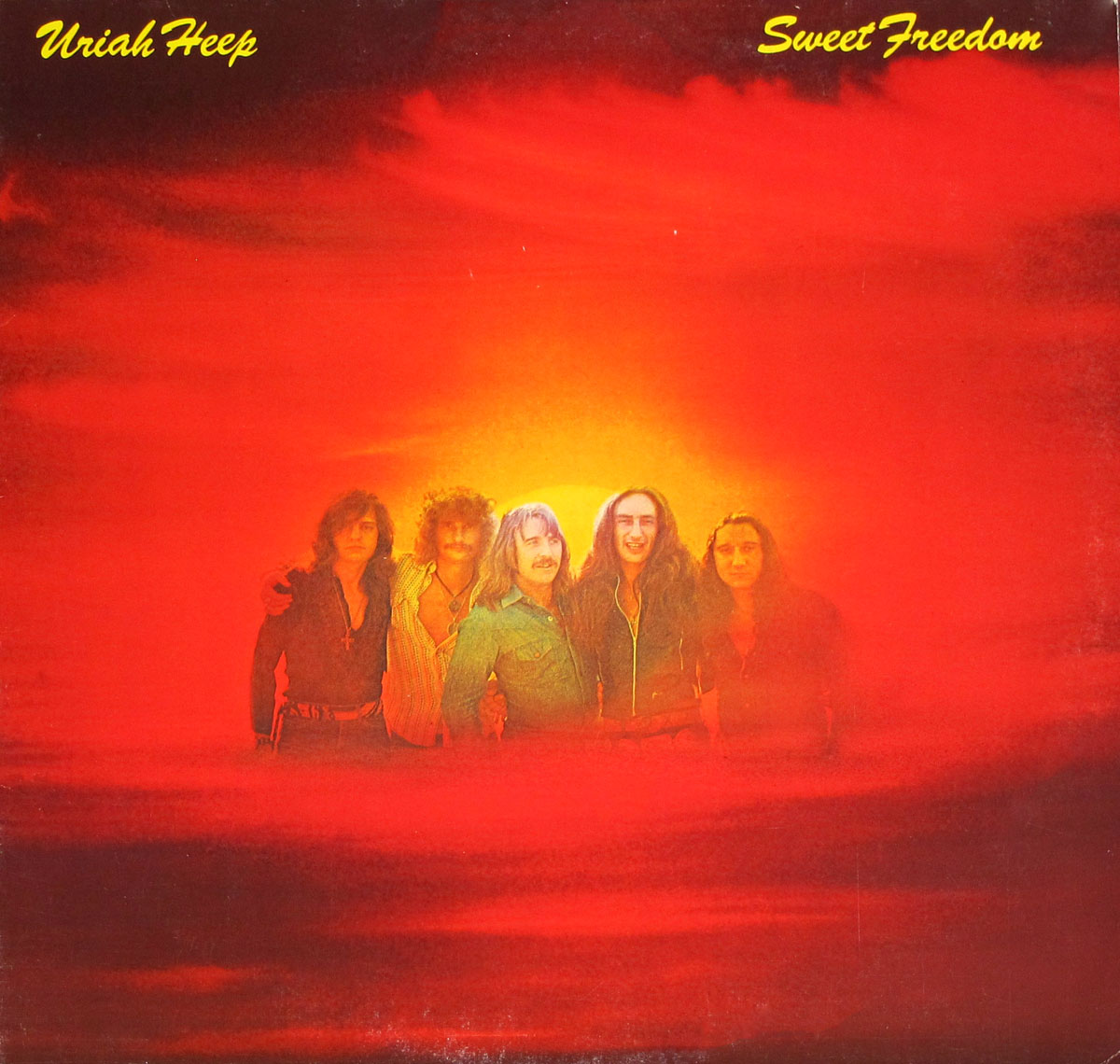

I don’t file Uriah Heep under “classic rock” the way a librarian does it. I file them under that early-70s moment when bands still believed a chorus could kick a door off its hinges, and the Hammond organ wasn’t decoration—it was a weapon. "Sweet Freedom" lands in September 1973, their sixth studio album, and it sounds like a group that’s stopped asking for permission.

Drop the needle and the first thing you notice is the band’s appetite. They don’t “blend genres” like some polite fusion act—they lunge. "Stealin’" struts in like it already knows the crowd will sing back, while "Seven Stars" drags a bluesy ache across the floorboards. And the title track "Sweet Freedom" doesn’t hurry; it stretches out, lets the room fill up, then leans harder. Call it hard rock with prog muscle if you need a label, but it behaves more like a live animal than a style tag.

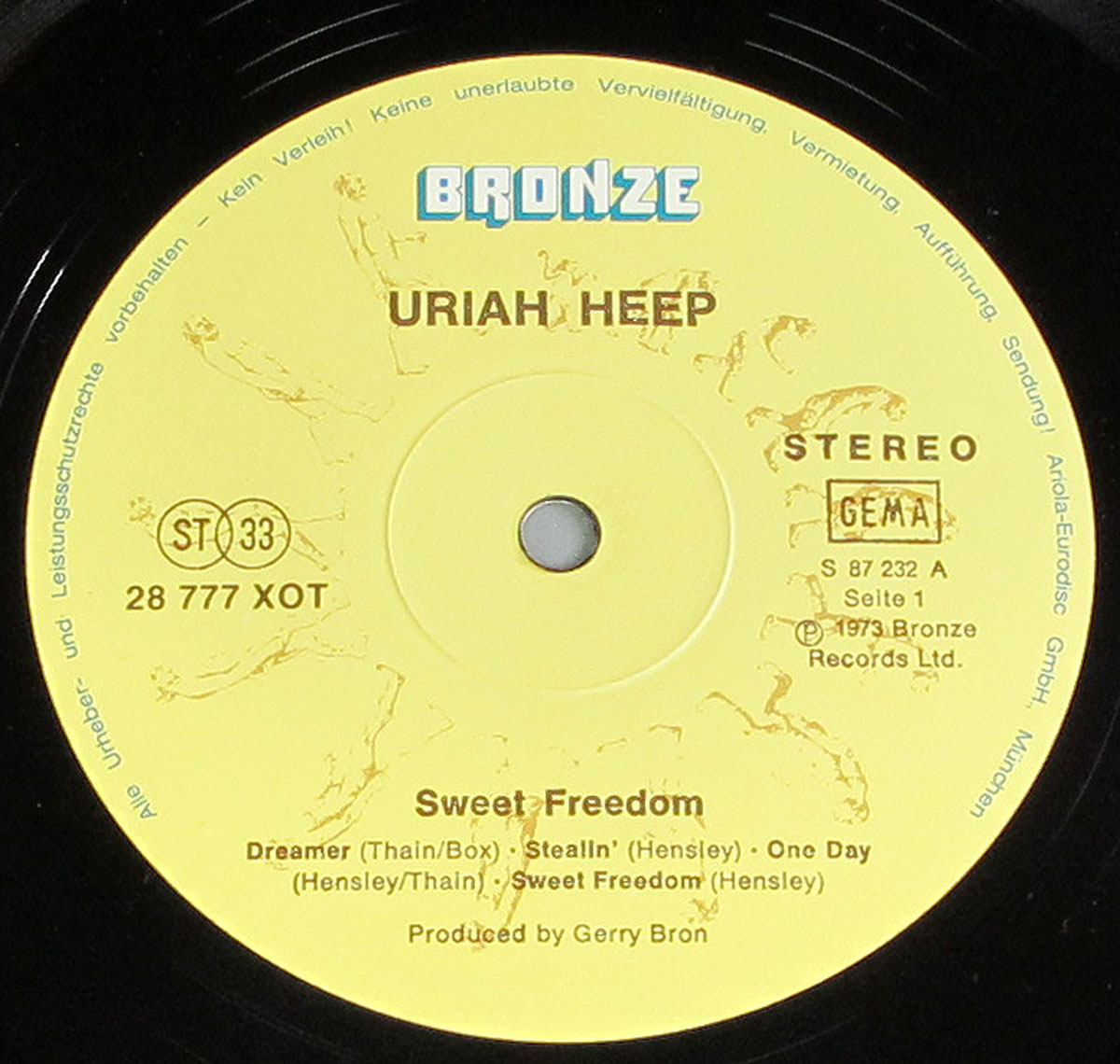

This particular copy matters too: Bronze cat. no. 28 777 XOT, made in Germany—one of those European pressings that collectors clock instantly because the whole thing feels a bit more “built” than disposable. Sleeve, print, that quiet confidence of a record meant to be handled, not just streamed and forgotten.

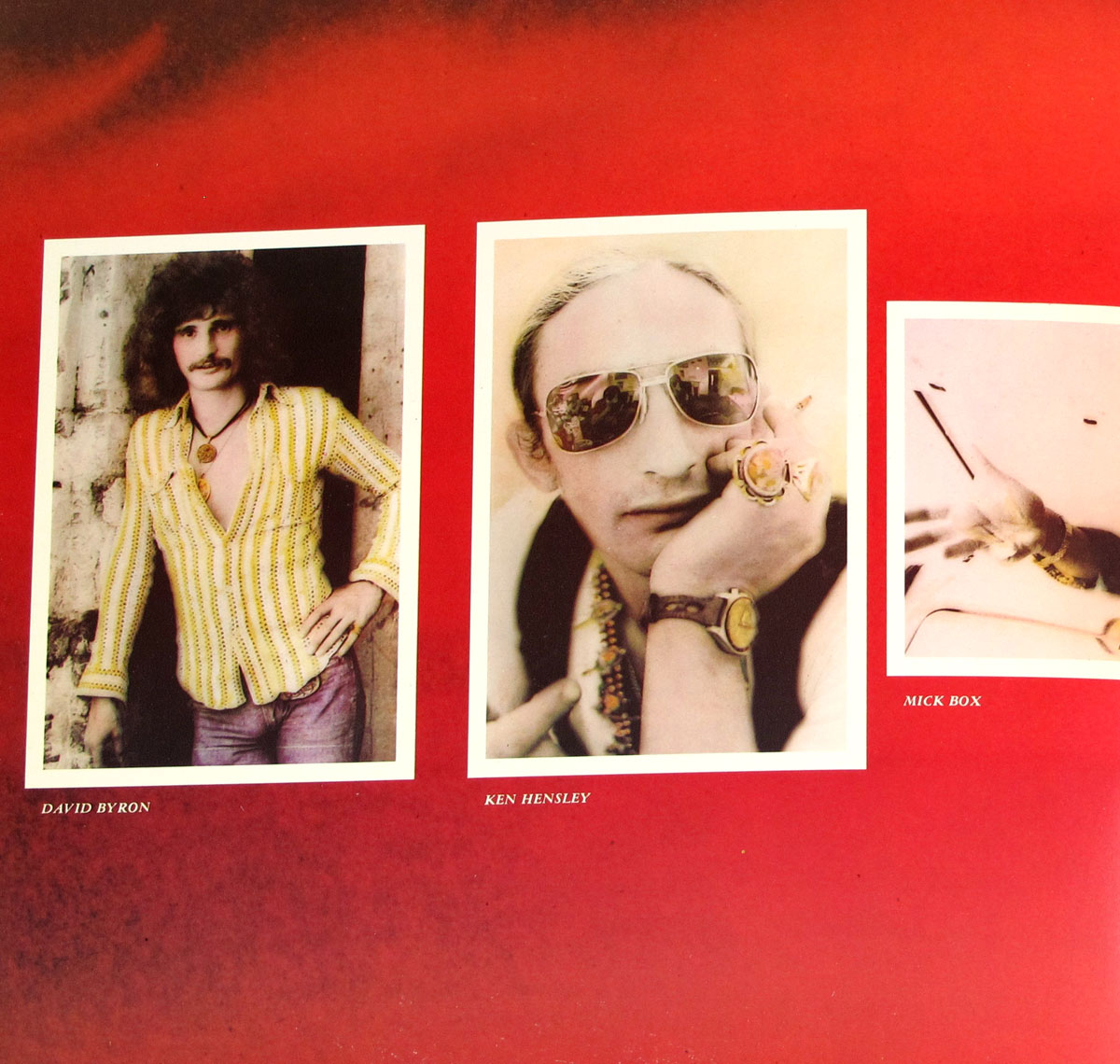

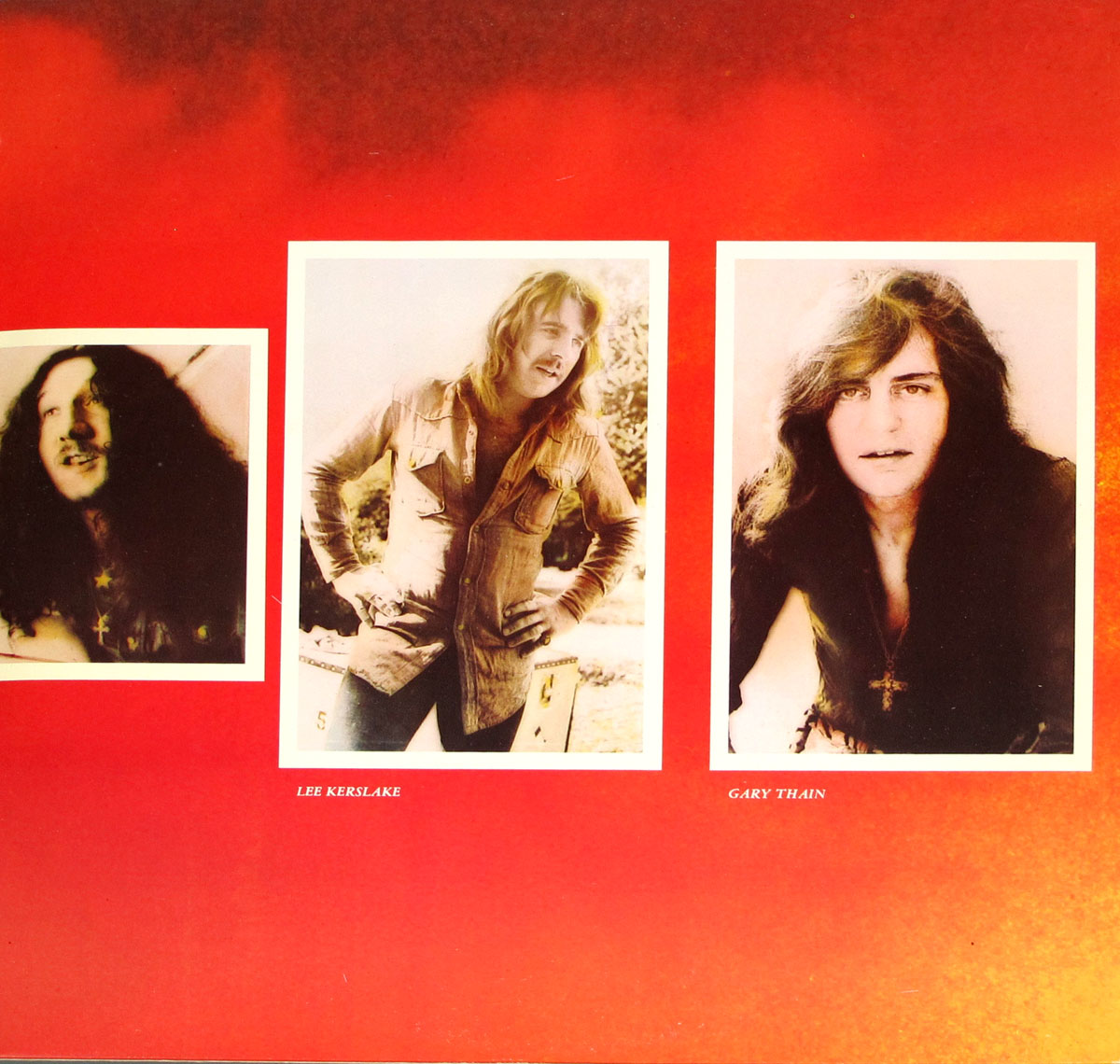

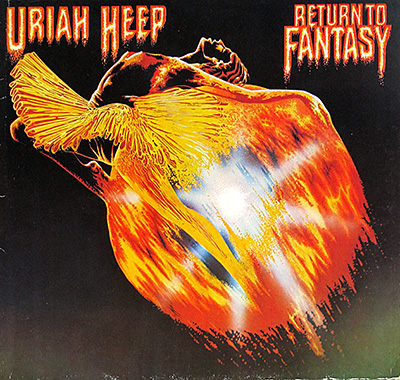

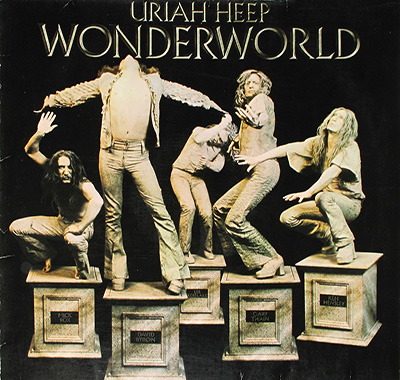

The gatefold is the real sales pitch here, and not in a cheap way. You open it and it’s like stepping into the band’s little private hallway—lyrics, credits, the stuff that tells you real adults made this with budgets, arguments, cigarettes, and late nights. The bronze statue cover isn’t “mysterious” in a brochure sense; it’s cold, heavy, slightly smug. Perfect, honestly. The music inside has that same weight: not fast, not flashy, just convinced.

Let’s keep it factual, not fan-clubby: in the UK it peaked at #18 and hung around for three weeks. Not Top 10 glory, not a flop—just a solid run for a band that was already working hard for its place.

The best part is how the record rewards habits. You don’t play this once. You play it when you’ve got time to sit down, when you can read along, when the room is quiet enough to hear the spaces between the hits. Digital makes it “available.” Vinyl makes it present. And if you’re asking me, that’s the whole point—otherwise it’s just another file pretending to be music.