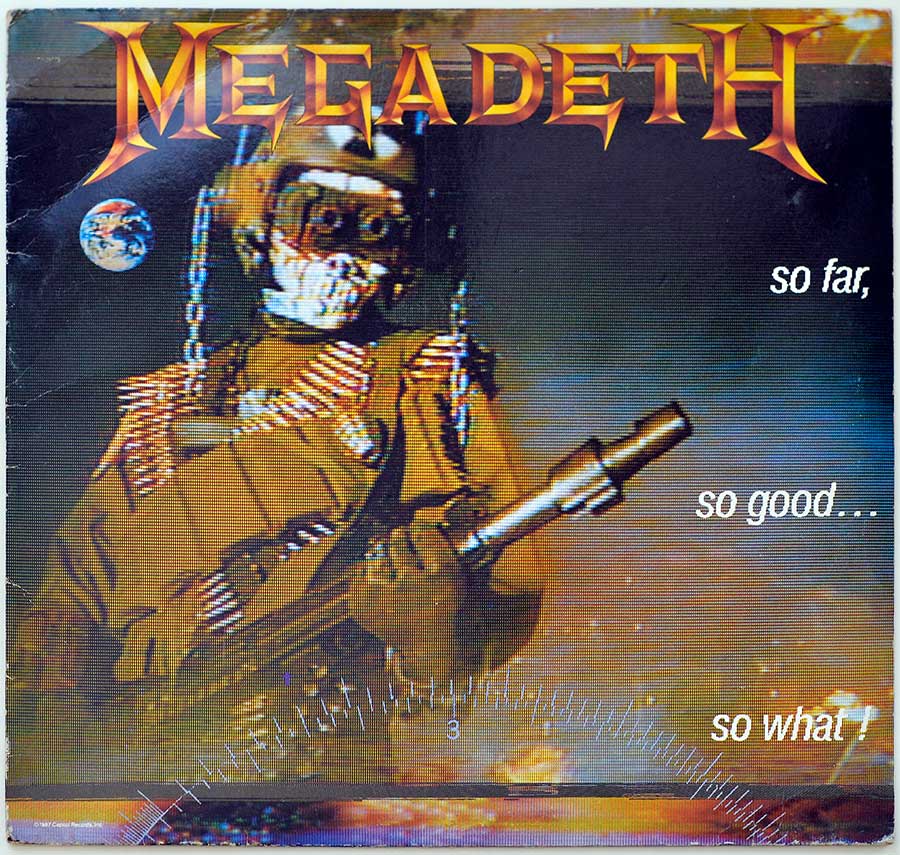

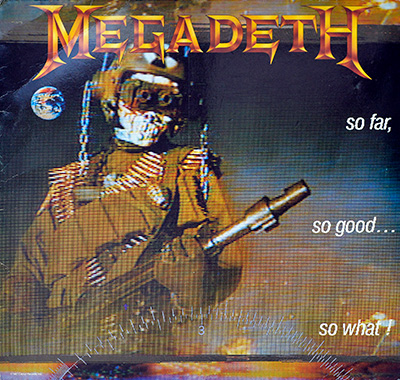

"So Far, So Good... So What!" (1988) Album Description:

In 1988, Megadeth didn’t sound like they were trying to win you over—they sounded like they were trying to outpace the cops. "So Far, So Good... So What!" hit the racks loud, fast, and kind of irritated, the way the best thrash did when it still felt like a scene and not a category. The riffs come off like snapped wires, the drums push hard on the corners, and Mustaine spits lines like he’s arguing with the tape machine itself. It’s not pretty, it’s not polite, and it’s got enough bite to make “Set the World Afire” and “In My Darkest Hour” feel like they’re happening right now, not safely back then.

1988, America: loud guitars, louder adults

The U.S. in ’88 had that late-Reagan stiffness—flag-waving confidence on TV, anxiety under the surface, and a weird obsession with “cleaning up” culture like it was a messy bedroom. Metal didn’t just get criticized; it got auditioned for public trial, with the PMRC-era scolding still in the air and “parental concern” acting like a badge. Thrash responded the only way it knew: turn up, speed up, sneer back.

Los Angeles metal was also splitting into tribes. Hair bands were still cashing checks, the underground kept sharpening knives, and the serious players were starting to look less like cartoon villains and more like hard-working psychos with discipline. "So Far, So Good... So What!" lives right in that tension—street-level aggression with enough precision to leave bruises in straight lines.

Where it sits in thrash, by comparison (no fan club speeches)

Same year, different flavors of danger were running around. You could feel the arguments in the music: cleaner versus nastier, “big” versus “real,” riffs as architecture versus riffs as blunt objects.

- Metallica were tightening the bolts and draining the color; Megadeth stayed twitchy and sharp-edged.

- Slayer were leaning into menace and atmosphere; this record prefers confrontation and speed-drunk momentum.

- Anthrax had the NYC bounce and punchline timing; Megadeth sound like they don’t laugh much.

- Testament were crisp and Bay Area proud; Megadeth feel more volatile, like the mix might start a fight.

- Overkill had that street-grit snap; Megadeth add a neurotic, stop-start intensity that’s less barroom, more backroom.

That’s the genre context: thrash behaving like a pack, but not agreeing on where the prey is.

Sound and feel: attack, space, and that “too wired to sleep” tempo

The record moves like it’s running on cold coffee and grudges. The guitars are cut with a bright, nervous edge—fast picking that doesn’t “flow” so much as it slices, then doubles back to slice again. The drums don’t float; they shove, especially when the grooves lock into that stomping thrash gait that feels like boots on plywood.

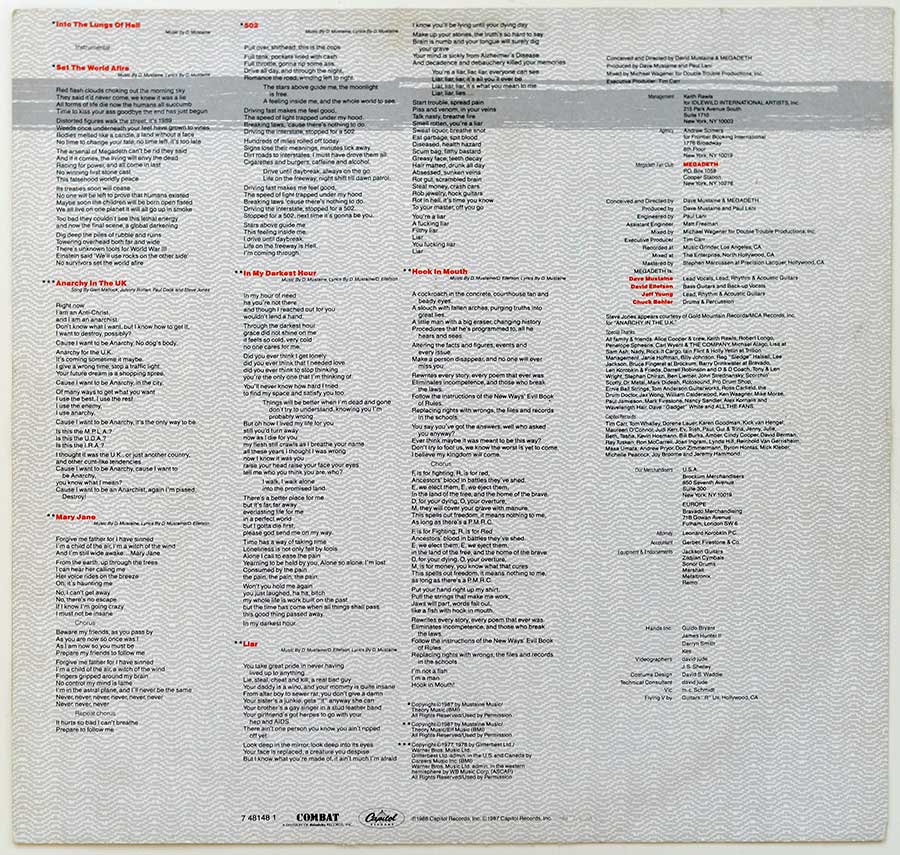

It’s also a record with mood swings. “Set the World Afire” has that scorched-metal churn, a riff that feels like it’s dragging sparks behind it, while “In My Darkest Hour” pulls the tempo back and lets the air turn heavy without going soft. And “Hook in Mouth” is pure irritation put to rhythm—tight, clipped, and pointed straight at the people who wanted warning labels on everything except their own opinions.

The funny thing is how physical it all feels: pick attack you can almost see, snare hits that land like someone slamming a door, and pauses that act like smirks.

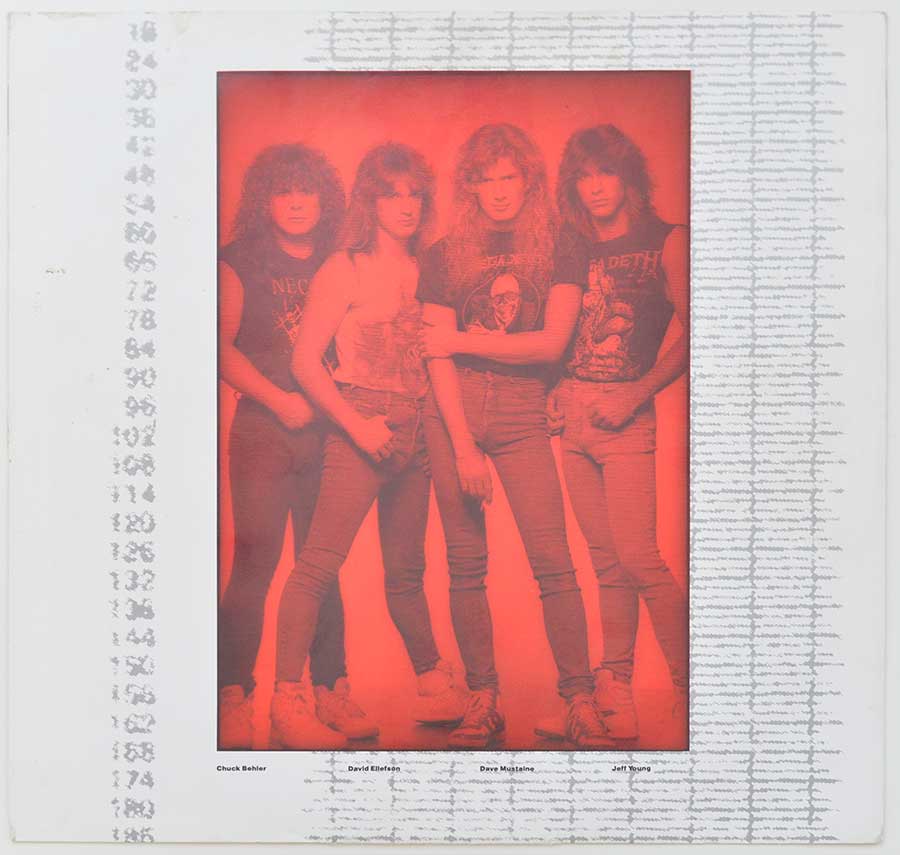

People who mattered in the room (and what they actually did)

Mustaine’s credit isn’t abstract here; it’s practical. He’s the one steering the arrangements—where the riffs turn, where the vocals bite, where the songs refuse to relax. You can hear a bandleader who wants control, and you can also hear why that might make rehearsal feel like a pressure cooker.

Production and mixing got messy in a very human way. Paul Lani was brought in, then the working relationship imploded, and Michael Wagener ended up handling the mix—two different sets of hands trying to make the same pile of sharp parts sit together. The end result isn’t “slick,” and that’s not an insult; it’s a record that keeps some grime under the fingernails instead of buffing everything into showroom shine.

The wild-card cameo is Steve Jones showing up on “Anarchy in the U.K.”—punk royalty dropping a guitar part into a thrash band’s version of punk’s most famous sneer. It’s a collision that sounds like it enjoyed the crash.

Lineup changes as cause and effect (not a timeline poster)

This is the one Megadeth album with Jeff Young and Chuck Behler, and you can feel the “new guys proving it” energy. Young’s playing is cleaner than the chaos around it, like a sharp pen line drawn over a noisy photocopy, and Behler drives hard without drifting into show-off mode. The band sounds like it’s trying to stay locked in while the floor keeps moving.

The catch is that a volatile band doesn’t just “have” lineup changes—the changes are the band’s weather. The writing and the pace demand discipline, and the personalities demand control, and those two things don’t always share a room quietly. By the time the touring dust settled, the lineup that made the record was already on borrowed time.

Controversy: the record didn’t start riots, but it did start arguments

No, this release didn’t trigger a headline-grabbing scandal like some moral-panic magnet. The controversy is more typical thrash stuff: parents, pundits, and a few self-appointed cultural hall monitors clutching pearls over aggression, speed, and lyrics that didn’t ask permission. The bigger argument came from inside the fan base—people bickering about the mix, the feel, and whether the band sounded “too muddy” or “just right.”

The most reliable talking point is “Anarchy in the U.K.”: some listeners loved the punk-meets-thrash stunt, others never forgave the lyrical flubs and the “USA” swap. The misconception is that the cover was some deep political statement; mostly it plays like a band grabbing a classic grenade, pulling the pin, and laughing at whoever ducks first.

One small, real-life vantage point

I remember hearing “In My Darkest Hour” late at night on a low-power rock show, the kind where the DJ talked too fast and the signal fuzzed at the edges. Even through the static, that main riff landed clean—like a hard thought you can’t shake.