In January of 1994, Glendora Wilson walked home from work to find a blues fan standing on the porch of her Third Ward Houston home. The fan was there to show her an ad in Living Blues, the world's most respected journal of African-American roots music. It was an ad she might well be expected to have an interest in, given that it featured a recording by her late husband, songwriter Harding "Hop" Wilson.

Promoted in the advertisement was a compact disc that had caused a sensation in the blues world. Houston Ghetto Blues was one of only two known recordings by Wilson, the semi-legendary composer of a song, "Black Cat Bone," that had been the nucleus of a Grammy-winning album by Albert Collins, Johnny Clyde Copeland and Robert Cray. Wilson himself rarely had been heard by blues fans; his first experiences with Houston's recording industry had so embittered him that he refused repeated opportunities to put his work down on vinyl, preferring the obscurity of playing neighborhood dives.

So the release of a fresh Hop Wilson disc might well be expected to be news. But less expected is to whom. Glendora Wilson looked at the ad with puzzlement. She was, to put it mildly, surprised to learn that her husband's last recording had been leased to companies on at least three continents since his death.

No, nobody had asked her about it. No, she had received "not one dime" for the rights to any of the music on the disc. No, she admitted, she wasn't sure she had any rights to any of that music. But, again no, nobody had bothered to check with her about those rights either.

Given that the CD had been released by Rounder Records, a label with a long history in folk and roots music and one generally regarded with respect, Glendora Wilson's ignorance about what was happening with her late husband's heritage might seem odd. But for anyone with much knowledge of the scuttlebutt of the Houston music business, a possible answer to the question of why Glendora Wilson remained in the dark could be found by looking on the back of a copy of Houston Ghetto Blues. Printed there is the simple declaration: "Original production by Roy C. Ames."

Roy Ames. He, too, has a long history in roots music. But as for respect, well, that's another issue altogether.

Making a name for himself

Ames' name, until recently, was little known outside of Houston. But the advent of digital technology, coupled with a trendy fascination with the roots of rock'n'roll, has made vintage blues recordings more accessible today than when they were first recorded.

This rebirth of the blues has turned attention to Houston, the source of many previously little-known blues masters, and to Roy Ames, whose Houston-based Home Cooking Records has become a hotbed of rediscovered blues music. According to local blues historian Aaron Howard, who last year wrote a short, laudatory profile of Ames for Public News, Ames has up to 8,000 master tapes stored at his home and office, tapes that contain performances by a plethora of Gulf Coast artists. With this vast reserve of master tapes to either put out on Home Cooking or lease to American and foreign labels, Ames now is one of the most successful people in the Houston music business. In addition to vintage and current recordings, Ames offers record stores and mail-order customers a wide selection of concert videos and posters, and does a lucrative business leasing the rights to archival photographs to recording companies for cover art.

Ames, a 57-year-old native of Beaumont, Texas, now lives and works in West University, Texas, operating Home Cooking Records out of a postwar bungalow. He tools around town in a Jaguar, his signature car ý and a sign, perhaps, of how far he's come from his East Texas origins.

Ames' history in Houston recording is long, and, at least as he tells it, important. In many ways, he's a caricature of a common feature on the Gulf Coast music scene: the independent record producer who lets nothing stand in his way. Like a Huey Meaux or a J.D. Miller or, most famously, a Don Robey, Ames has been portrayed as a man who got unknown music out to the masses, even if he had to occasionally cut a corner here and there to do it.

He seems to have been a fairly minor player until recent years. Roy Clifton Ames, a k a "Sweets," a k a Roy Clifford Ames, has said he got into the music business in 1959, when he was helping his father run a car dealership in Beaumont. At some point in the early 1960s he started Aura Records.

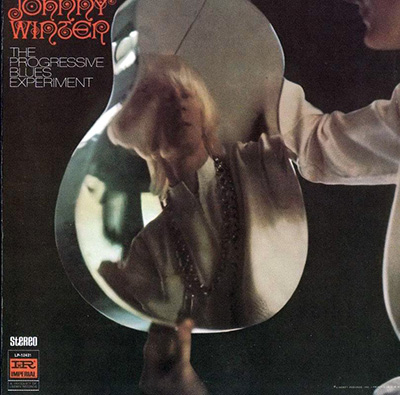

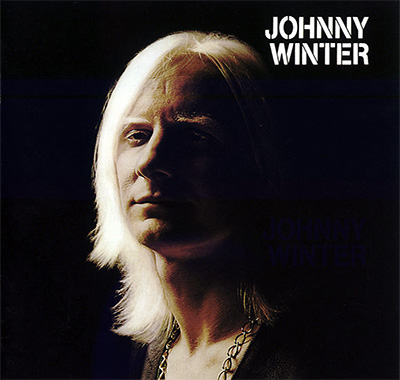

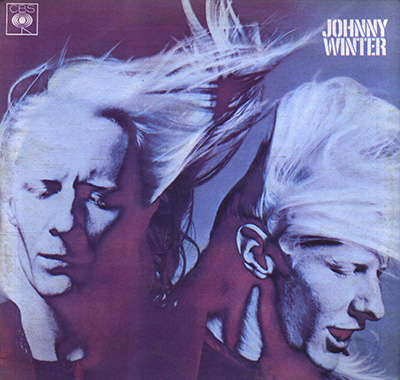

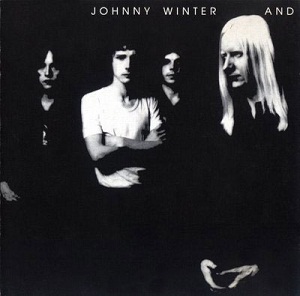

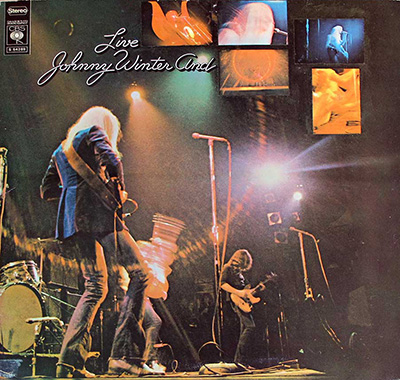

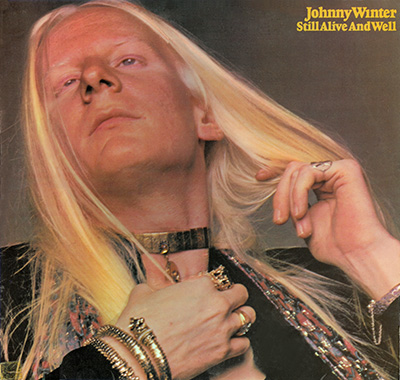

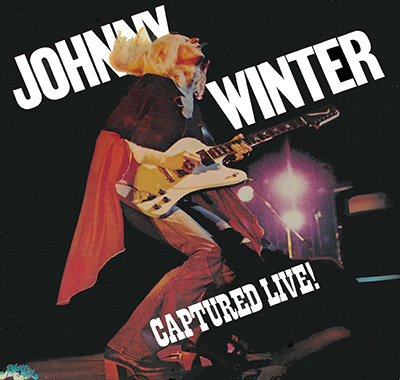

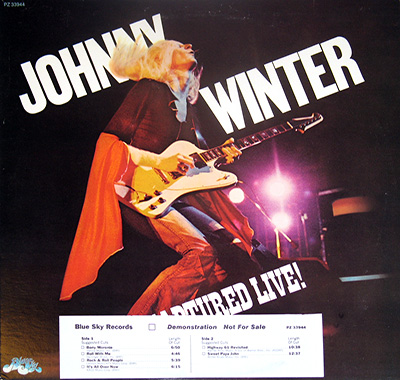

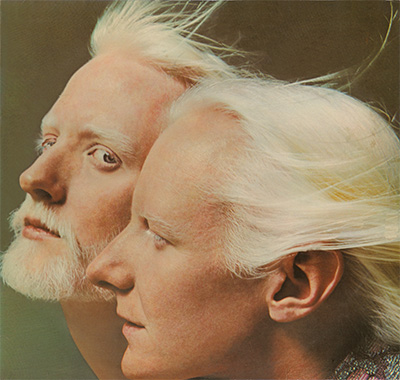

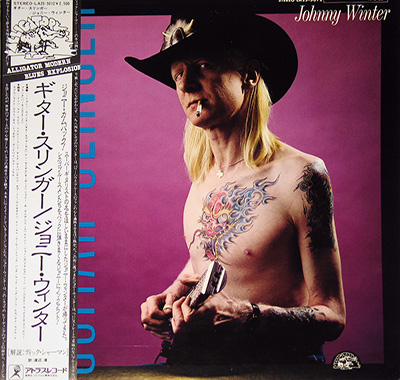

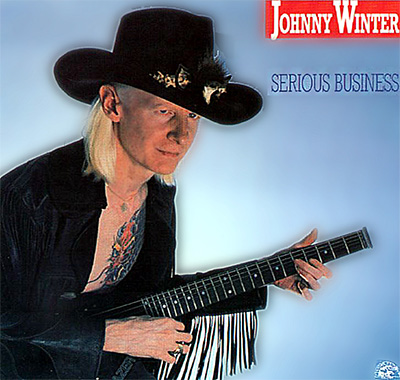

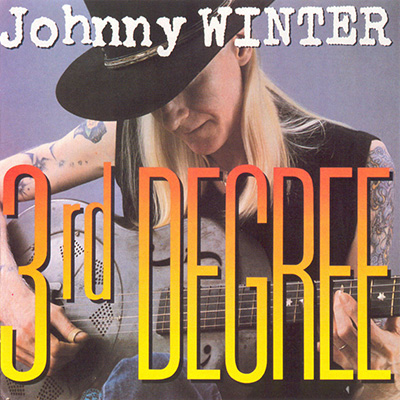

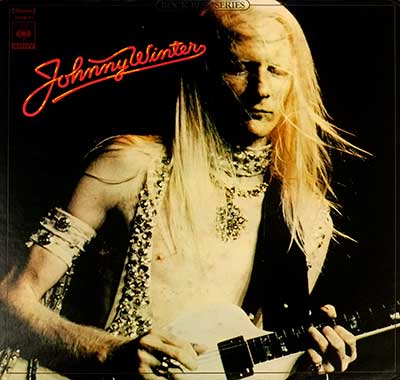

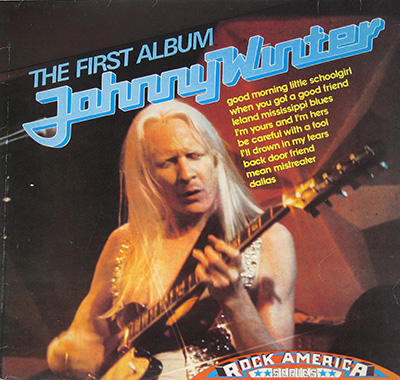

By the mid-'60s, Ames was managing a young albino guitarist from Beaumont named Johnny Winter. By that time his record company was called Cascade, and it released two records in 1965 or 1966 by bands called the Great Believers and the Insight; both featured Winter on lead guitar.

In addition to managing several emerging artists for short periods of time and producing a handful of local-label 45s, Ames worked in varying capacities for several record distributors. He claims to have worked for Motown, and his start in the music business may have been with King Records, where he says he was Texas sales manager. A few years later, Ames was working as a record promoter and distributor for Don Robey's Duke/Peacock label, which dominated the Houston recording business for two decades.

Roy Ames worked several places and did many things. But one thing he did consistently was never pass up an opportunity to acquire master tapes of Gulf Coast artists, among them Hop Wilson, tapes that have since turned up on blues albums and compilations worldwide.

Other issues

For about a decade, from the mid-'70s to the mid-'80s, though, most of those tapes lay fallow while Ames dealt with other issues.

On September 16, 1974, a federal grand jury in Houston indicted Roy Ames on one count of conspiracy and ten counts of mailing obscene material. Ames was arrested and charged with two counts of sexual abuse of a child. Six charges of compelling the prostitution of a minor were filed against Ames on June 16, 1975. On July 26, 1975, the Houston Chronicle reported that two more tons of obscene material were seized in a raid and described Ames as the leader of the ring.

Whatever the source of Ames' income at the time, he was able to afford competent legal counsel, and bail totaling $310,000. The eight charges filed in 1975 eventually were dismissed in 1979. Reasons included the difficulty of getting teenage boys to testify about being victims of sexual abuse and Fourth Amendment problems with the search warrants.

But another possible reason is that Ames was already serving time in federal prison. Beginning Nov. 23, 1975, Roy Ames had been in a sex-offender therapy program at the federal prison hospital in Springfield, Missouri, while serving three four-year federal sentences for conspiracy and distribution of obscene material in the mails.

After being transferred to the federal prison in Big Spring, Texas, Ames was indicted on mail-order child-porn charges by a federal grand jury in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1981. Those charges resulted in a five-year sentence at Latuna Federal Prison in El Paso. In conjunction with the Massachusetts charges, Ames was charged in Houston by state and local authorities with wholesale promotion of obscene materials in 1981.

Ames was paroled from Latuna in 1986. Since then, aside from a DWI in 1990, Ames has steered clear of the criminal courts. The federal Parole and Probation agency lists his current parole status as "inactive."

Home Cooking

While Ames was fighting his battles over pornography and sexual abuse, he was also founding Home Cooking Records and Clarity Music. (The latter, as it happens, claims publishing rights to all 18 songs on Hop Wilson's Houston Ghetto Blues, as well as to hundreds of other songs written and recorded by dozens of Gulf Coast artists.)

Ames already had released three Home Cooking CDs in 1988 ý by T-Bone Walker, Juke Boy Bonner and Lightnin' Hopkins ý that were credited with revitalizing the label and pointing to its new emphasis: little-known Houston blues.

By the early 1990s, the first three discs on the Home Cooking label had been joined by dozens of others. American companies had joined the European and Asian collectors' labels eager to lease masters from Ames. Rare posters featuring moments great and extremely obscure in Texas music history were offered to eager fans. But according to more than a few blues musicians, Ames' niche was carved out of their hides.

Illegal?

Allegations of recording rip-offs literally are as old as the blues itself. W.C. Handy, the author of "Memphis Blues," recounted in his autobiography how he was swindled out of the rights to the first popular blues song ever copyrighted. The powerful play "Ma Rainey's Black Bottom" is centered on black artists at the mercy of the recording industry in Chicago in the 1920s.

But proving the allegations often has been difficult, in part because blues artists have not always paid the keenest attention to contracts, and in part because the morass of recording laws can make some things that might appear unethical in fact perfectly legal.

But while Ames' conduct as he has moved toward the top of the blues business might be acceptable in a court of law, many of the performers he has worked with have no problems saying that in the court of human decency, his conduct was unacceptable in the extreme.

"The worst"

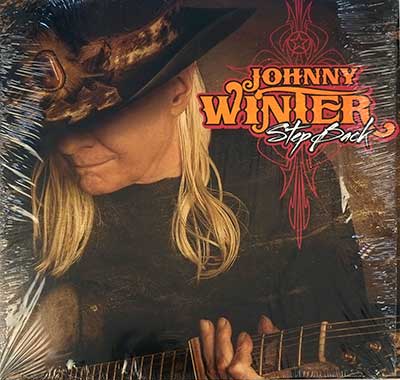

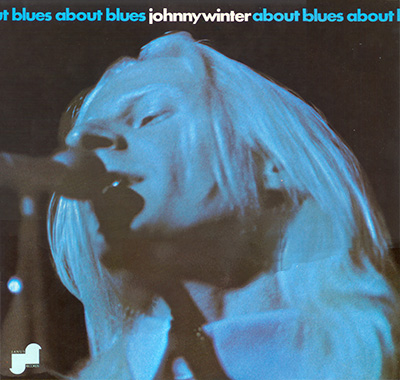

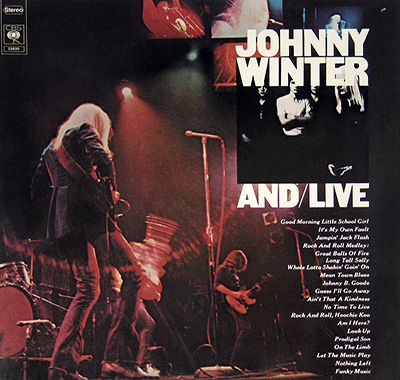

Johnny Winter, who attributes his success to getting out of Houston and moving someplace where a musician will be treated fairly, was eager to discuss his former manager (and a man who is still releasing Winter's music).

"Roy Ames is the worst," Winter said. "When I see Roy's name on (an album), I know it's going to be trouble. If he put it together nobody is going to see a cent of it, except him that's for damned sure. This guy has screwed so many people it makes me mad to even talk about Roy. It's hard for me. My lawyer always says, 'You'll never get anything from the guy. He's so dishonest and so hard to track down that even if you sue him and win, getting the money is a whole different thing.' Maybe things have changed. I hope they have; maybe we can get him."

A much more recent addition to Home Cooking's roster is Leonard "Low Down" Brown, a talented songwriter whose blistering guitar skills keep him busy around Houston's club scene.

"I met with him, and we didn't get around to talking about any business," Brown says. "We went in and laid down four or five tunes. These were all original songs. It was just a rough sketch, what you call a scratch track. Roy did not want to come to any contractual terms; he kept sidestepping the issue and everything. I just abandoned the project.

"The next thing I know he had put it on some kind of CD. I couldn't believe it. I saw me, Al Betis and Little Junior One-Hand. It said Texas Guitar Greats Volume 2. I called Roy and asked him about it. That's when we got into it. I said, 'Roy, you're using my music and you have no agreement ý and you're not paying me any royalties. I don't think what you're doing is right.' He said, 'Well, if you don't like what I'm doing, sue me.' And then he hung up on me."

Brown is harsher with his own work than the cruelest critic. "I'm ashamed because it's bad stuff, a really poor, slapped together, piece of work."

For years, Ames has played successfully on the harsh reality that legal recourse is beyond the reach of many of those who created the music he sells.

"He looks for people that he thinks are up and coming," Brown says. "He looks for people that don't know much about the music business or that are really poor people, couldn't possibly hire a lawyer. He leads them down the path thinking that he's going to help them, when he's really just out to rip them off. Once he gets you on tape, you can forget it."

Alan Govenar, the author of the seminal Texas music book, Meeting the Blues, also expressed concern about being identified as saying negative things about Ames. Govenar initially was reluctant to speak for attribution about Ames, but after a long pause, the dean of Texas blues historians said in a scholarly and measured tone, "Based on my research, Roy Ames had questionable dealings with the musicians that he recorded. No contracts with these musicians to my knowledge have ever been made public. It is difficult to understand how he has been able to, since the death of so many of these great Houston musicians, release these recordings. Why were they never released during their lifetimes? It is questionable and doubtful that he has the rights to the music.

Preying on the dead

One artist whose works appeared on Home Cooking after his death without his family's knowledge was Weldon "Juke Boy" Bonner. Bonner's daughter, Deborah Nicholson, had never heard of Roy Ames or Home Cooking in 1991 when she went searching for some of her father's albums.

"I saw these two new albums. One was a memorial type thing, and the other one was just some of his songs. And I saw they were put out in '89, and I said, 'Who put this out?' I called (Ames), and he said he wouldn't have no kind of way knowing about the royalties, because he had sold the records outright. My dad had sold the music; we weren't entitled to any more. He said something about how he had told my dad to get his business life together so he could get royalties."

Ames had good reason for portraying himself as a sorrowing friend of Bonner's, and, by extension, his family. According to Nicholson, "He was asking me if I knew anything about my dad having tapes that weren't published yet." Perhaps envisioning more unexpected discoveries, Nicholson declined to offer Ames any more of her father's music. Then Ames had another request: "He wanted to know if I had any kind of recordings or movies or pictures. He's off into something."

The poster business

The "something" is Gulf Coast blues memorabilia. Along with music, Home Cooking also offers videos and posters, among them a promotional showbill advertising Elvis Presley's 1954 appearance at Cook's Hoedown Club. The posters were originally sold by Home Cooking for between $150 and $200, and Elvis collectors are now buying them on the memorabilia circuit for more than $500. Some collectors, though, have begun to wonder about their authenticity, pointing to their surprising crispness for posters some 40 years old, and also pointing to a curious resemblance between the posters and an ad that can be found on Houston Post microfilm at the Houston Public Library.

Another poster offered by Home Cooking...it's not made clear in the ads whether the poster is an original or a reprint...advertises a show at the legendary Double Bayou roadhouse in 1956. T-Bone Walker was the headline act, and below that in large type is the name later used by someone who, in 1956, was one of the hottest of the Shady's Playhouse teenage guitarslingers Joe "Guitar" Hughes, who appears on many of Home Cooking's foreign and domestic recordings.

"That crook. I call him the Texas Music Rapist." Hughes exploded angrily. "He's got some posters out on me and T-Bone Walker that are phonies. I called him, and he tried to convince me they was real, like I supposed to be Winnie the Po-Po or something. I told him in the first place, I never played Double Bayou with T-Bone, and in the second place I didn't start using 'Guitar' in my name 'til about '85."

When interviewed, Ames disputes that claim. "He's the one that told me that he always played with T-Bone there. I thought I was doing him a favor. Those posters get them tremendous publicity."

Hughes, who joins the chorus denying ever having signed contracts with Ames, is one of the very few artists in the Home Cooking catalogue ever to receive any compensation. "I called him about the album, about my royalties, and I think one time he sent me a hundred and fifty dollars. He didn't send me no write-out. The second time he was supposed to bring my royalties by my ex-manager's, and instead of bringing some money he brought a box of 25 albums for him to peddle. I got magazines from all over the country and Europe, where his ads are in there, T-shirts, posters, all kind of stuff. If you wouldn't frequent these magazines you wouldn't know."

The find of a lifetime

The decade of trials and appeals had depleted Ames' finances ý at the 1981 trial he had plead poverty and receive court-appointed counsel so as soon as he was released from prison he began making the rounds. Glossing over the reason for his long absence, he found many artists who believed his tale of imminent fame and fortune. Ames also made the acquaintance of Andy Brown. It was, for Ames at least, a most fortuitous event.

Today, at 24, Andy Brown is a tall, red-headed human encyclopedia of postwar Texas music. He reflected on his senior year at Lamar High School, when, consumed by a passion for blues and R&B, he found in the phone book a name he recognized from the album covers.

The name was Roy Ames, and when Brown called him, he found Ames patient and cordial in answering the 17-year-old's questions about artists both obscure and famous. So when Brown made the "find of a lifetime," one of the first people the excited teenager called was Roy Ames.

In the back of a long-abandoned Fifth Ward building was a closet filled with box after box of Duke/Peacock publicity photos and negatives, canceled royalties checks endorsed by the artists, statements, invoices, letters, telegrams ý a treasure trove for memorabilia collectors.

"Man, it was an incredible find," Brown says. "Just hundreds of original, never-before-seen photos and stuff."

Ames arranged to sell usage rights for the photos to Ace Records in England, a deal that netted Brown around $1,000. Brown doesn't know how much the rights were actually sold for, but at the time he was satisfied with the payment especially since he retained the photos themselves.

Eventually Brown began having reservations about "exploiting" what he viewed as a near-sacred trust, even though he had rescued the items from almost certain destruction in an open, crumbling building that had been vacant for more than a decade.

"After that (Ames) said, 'I've got this deal worked out with P-Vine to sell them the rights.' I said OK," Brown remembers. "Hell, I was broke, but I was feeling kind of guilty too. I didn't like making money off that stuff. So I took it all over to his house one day, and the next thing I knew, he auctioned it all off and sold it to God knows who for how much money. And cut me out completely. His explanation was that I had got my cut the first time we leased the photos."

This was vastly different from what Brown had planned. "I felt guilty that first time after we sold the rights to Ace, making this money off of these guys. Of course a lot of them were dead or you couldn't find them, but after that I got the feeling I didn't want to do this any more. I was going to just keep the pictures over at my house and show them to whoever wanted to see them."

Brown describes Ames as someone "who never questioned what he was doing, never felt a tinge of conscience and was unshakable in his belief that he was right." Ames, Brown says, "could have been the greatest used-car salesman on Earth."

A book, Duke/Peacock, written by noted musicologist Galen Gart and Roy Ames and lavishly illustrated with photos from a closet in the back of the old Duke/Peacock Records building, was published in 1990. It's regarded as one of the essential components of a blues fan's library.

Galen Gart remembered, "I saw an ad in the back of Goldmine which advertised an auction that Roy was having. The Duke/Peacock logo got my attention immediately. I said if there are photographs involved, there's probably a book here." After selling many of the photographs in what Gart described as "a straight cash purchase," Ames agreed to help research the book if he would be listed as co-author. Although Gart said, "I had a good working relationship with Roy," he was uncertain how Ames had acquired the photos, saying, "You'd have to ask him on that." Although Gart had heard from a friend about Ames' pornography convictions, "it didn't influence me one way or another."

The Rockefellers rip-off

The Duke/Peacock find was a boon for Ames, but it wasn't his main focus. While he built his reputation as the international source for authentic Houston blues recordings and photos, Ames continued to add to his stash of audio and video recordings. About three years after his release from prison, he persuaded a number of Houston artists to perform at a showcase at a nightclub called Rockefellers. The artists were told the purpose of the event was to shoot a concert video that would establish Houston as the blues capitol of the world.

What eventually came of the project was Saturday Night at Rockefellers, a compact disc whose contents have been widely anthologized on Home Cooking compilations. Several noted Houston artists appear on the CD, and all insist they were unaware of the recording until it appeared in stores.

"We were told it was for a video," says harp player "Sonny Boy Terry" Jerome, who was there. "Nobody knew it was going to be on a CD, and nobody signed a release form or anything. He had some little two-tracker backstage. The next thing we know, the guy's putting out CDs left and right on everybody.

"The original songs is what really pisses people off. Getting original music published is heinous. And when you do a live version of a cover, you're supposed to sign a release form or he can't put it out."

A version of what Jerome calls "an original instrumental that I'd been playing around town for years" appears as "Mr. Rockefeller," published by the Ames-owned Clarity Music, on Texas Harmonica Greats, one of the Home Cooking discs to use the Rockefellers material. Jerome says, "I had never published it. It was just a blues instrumental, but he didn't have my permission."

Another tune published by Clarity that appears on Saturday Night at Rockefellers is "Wigs & Pigfeet." According to Kenny Abair, another of the Rockefellers performers, that is actually "Wig Song," written by the near-deified Sam "Lightnin' " Hopkins.

When asked about the Rockefellers album, Ames dismissed complaints about his business practices as "grumbling." His memories of the arrangements for the evening are much different from the those of the artists. "What I did there was simply hire musicians to come and put on a show," Ames says. "And I informed them that we were going to make a CD and a video of it. Anyone that tells you otherwise, they weren't listening because everybody was there.

"I paid everybody at the session." he adds. "There would be no royalties on that, because of the enormous number of people. How would you pay royalties? I sat back there at the back. They certainly knew I was cutting a CD at the same time because I had a portable recording studio there. I mean it was expensive. I sat back there and paid everybody by check. I wrote checks back there for over an hour after the show." Ames was unsure if the artists had signed contracts. "Maybe I just wrote a little something on the check."

When asked if the appearance fee he paid the artists also purchased the publishing rights to the songs they performed, he responded "Oh, boy, are you asking a technical question." When the issue was raised again a few minutes later he this time responded "No, the publishing rights are completely different." When he was informed that one source of "grumbling" was Sonny Boy Terry, upset over the Clarity Publishing on his original song, he said, "Then he needs to come in and sign a writer's contract."

Quality control

What upsets many artists more than even the question of royalties is the question of quality. Among the 8,000 master tapes reportedly in Ames' possession there is thought to be some truly awful stuff, tapes that would have been wiped clean with a magnet if the artist or his heirs had any say in the matter. And even when everything clicks, any recording is going to need some polishing, dubbing or engineering somewhere to make it the best it can be. But all that costs money.

In 1955, vocalist Jimmy "T-99" Nelson decided to get serious about being married and just dabble with music. In 1965, Ames asked Nelson to do some recording just to see what happened. Since the session would feature Arnett Cobb on sax, Calvin Owens on trumpet, and Spooky Dancer on organ ý an all-star Houston lineup ý Nelson agreed to lay down a few sides without a contract.

Although Nelson signed a one-year contract in 1970 with Ames, he assumed the material was dead. "I did these things for Ames, and then he went off to prison for so many years," Nelson explains. 'That was stuff I was sure would hit the big time again. This guy had it under wraps."

When Ames was released from prison, Nelson had hopes that the sessions might be resurrected. As it happens, they were, though not in the manner Nelson might have wanted. Shortly after his release, Ames began shopping the T-99 sessions he had under wraps for so long. And when he found a buyer ý Ace Records in England ý Nelson finally lost faith in Ames.

According to Nelson, it wasn't because he wasn't paid. "Roy sold the thing like it was. One of the cuts the drummer drops the stick on the cuff. The trumpet's too close to the mike, and some places it wasn't close enough. They could have fixed all that."

The album was released as Hot Tamale Man, named for an original song which Nelson says he holds the copyright on. Nelson was aware that the album had been released by P-Vine and Ace. What he didn't know, at least until recently, was that the album was available on Home Cooking, and that that ver sion said all the songs were the property of Clarity Music.

When informed of Nelson's surprise at the album, Ames said, "I wouldn't know where he is or how to find him. Is he still alive?" (As it happens, Jimmy "T-99" Nelson's phone number is the same as it was the day he first cut "Hot Tamale Man.")

Holly Bullamore, manager for Johnny "Clyde" Copeland, is another who reports constant surprise at what's available on Home Cooking. She says that every time she visits her favorite Chicago record store she finds more Home Cooking reissues from sessions Copeland cut both decades ago ý and fairly recently. Somehow, as independent studios opened and closed and merged, dubs of forgettable sessions found their way to Ames.

Like many people in the industry, Bullamore seemed absolutely baffled by Ames' audacity. Copeland, who appears on many Home Cooking CDs, was once hired to do a commercial for Miller Lite. On Home Cooking's The Three Sides of Johnny Clyde Copeland is a song titled "Commercial." Bullamore marveled, "He took the audio track from a television commercial, put it on a recording and put publishing on a song that's owned by Miller Brewing."

Ames' audacity may come back to haunt him. If he had stayed with putting out records by people that are either deceased or too poor to follow up on their complaints, he might have spent his life being the gossip of the music community.

But now an attempt to profit from his best-known connection could cause serious problems. Roy Ames' claim to fame, his credentials when questioned, is that he was Johnny Winter's manager and producer back when Winter was an unknown.

But allegations have surfaced that Ames might have sold rights to Johnny Winter recordings that he didn't own in the first place to Relix Records in New York, which specializes in archival reissues.

Other squabbles are appearing on the horizon. Jim Bateman, manager for Clarence "Gatemouth" Brown, says he has an attorney looking into issues related to Ames.Paul Verbernie, a Houston lawyer with an interest in entertainment law, says he's heard that a move is afoot to track down performers with complaints about Ames to see if a joint action of some kind might be possible. And George O. Jacobs, a B.B. King fan who prosecuted Ames when he was with the Harris County District Attorney's office in the mid-'70s, was curious how someone with federal felony convictions could legally be involved in an import and export business.

Meanwhile, Ames continues operating Home Cooking and Clarity, getting notice in the blues magazines, fielding complaints from Houston musicians, filling mail orders for CDs and collectibles, and saying that he's done nothing illegal, that misunderstandings happen.

But there are lawyers from New York to San Francisco circling around Home Cooking and Clarity Publishing. A record company with tentacles around the globe has messed with everyone from the Institute of Texas Culture, whose Bowie Street Blues Festival turned up as Saturday Night in San Antonio, to Sony and Miller Lite and Elvis Presley Inc.

As the lawyers begin to circle, Roy Ames may well consider everything that's happening to be a big mistake. If so, he could well be right. Only this time, the mistake would have been his.

Epilogue

This article first appeared in a somewhat lengthier version in the Houston Press, a New Times publication, on April 28, 1994. On August 2, 1994, a multi-million dollar suit naming Roy Ames and Jerry and Nina Green of Collectables Records (Home Cooking's distributor) as defendants was filed in federal court in Houston by attorneys David Showalter and Suzanne Tomkies on behalf of Leonard Brown, Walter Price, Pete Mayes, James Nelson, Clarence Green, Clarence Parker, Lee Frazier, Joe Hughes, Rayfield Jackson and Freddie Collins. That case, and others, is pending.