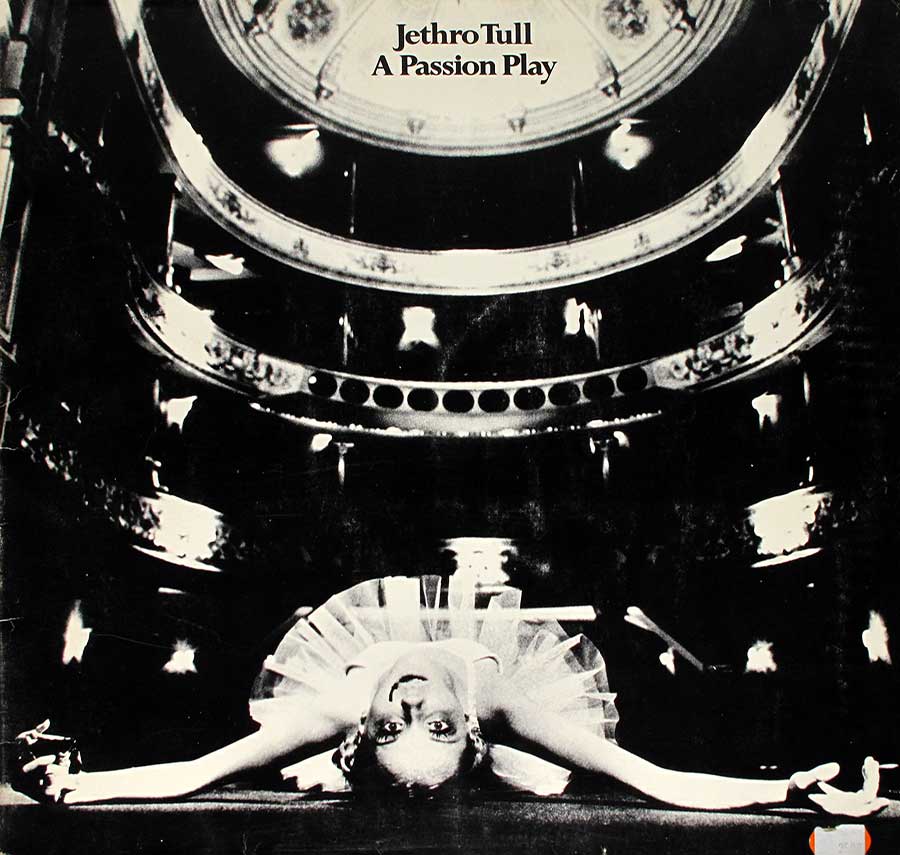

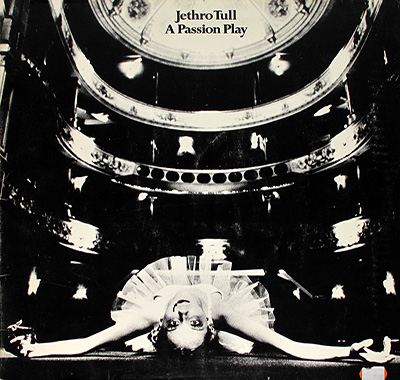

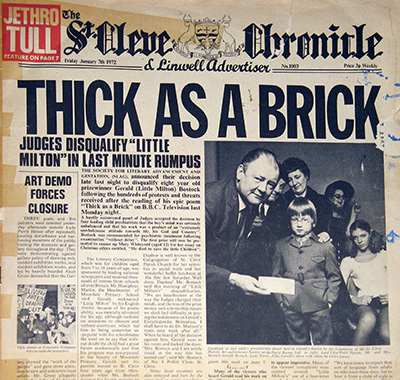

"A Passion Play" (1973) Album Description:

"A Passion Play" is Jethro Tull doing the funniest possible thing after "Thick As A Brick": going even deeper, even stranger, and still landing a hit. It is one long, continuous piece split across two vinyl sides, built like a stage show that refuses to sit down and behave. The heartbeat at the start is not “atmosphere” — it is a warning label.

Introduction on the band and the album

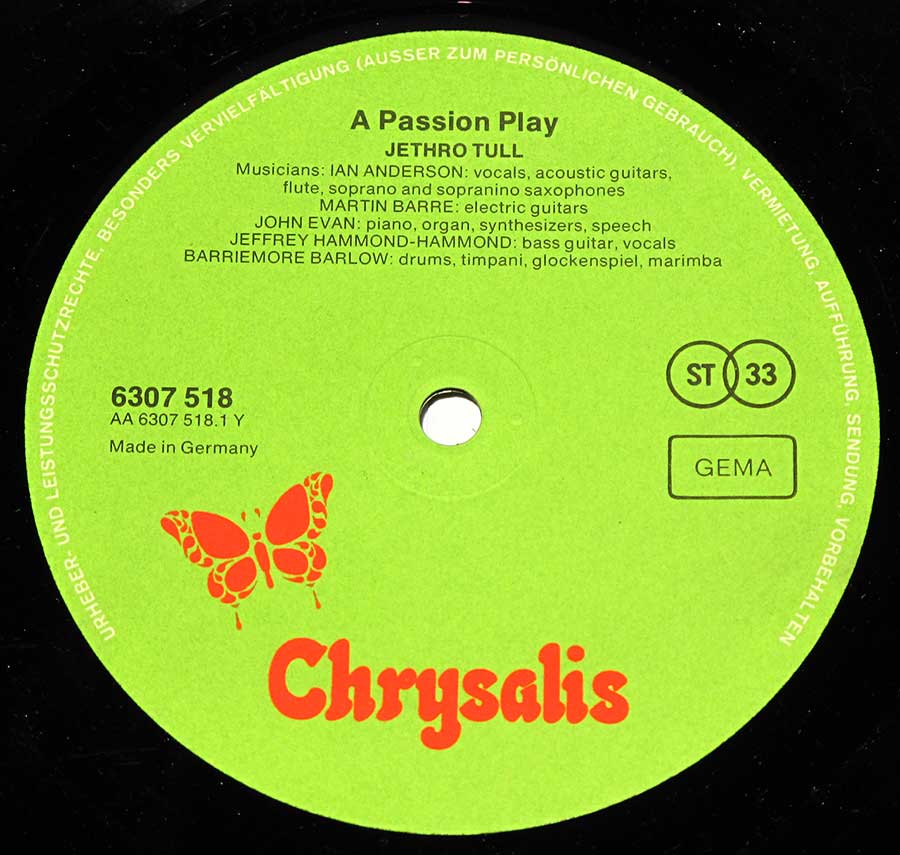

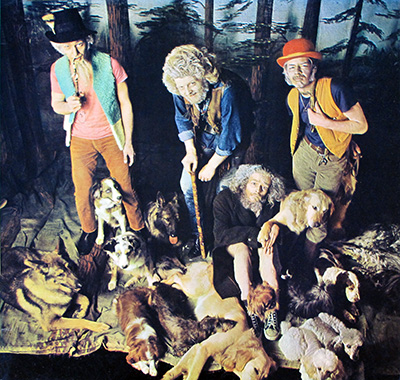

By 1973, Jethro Tull were not just a band, they were a moving target. Ian Anderson (vocals, flute) steers it, Martin Barre’s guitar keeps it sharp, Jeffrey Hammond-Hammond’s bass walks with a storyteller’s bounce, John Evan’s keyboards add theatre-kid sparkle, and Barriemore Barlow plays drums like he is trying to win an argument with the time signature. Put that lineup on a concept suite and you do not get background music. You get a commitment.

Historical and cultural context

1973 is prog rock at full height — big stages, bigger ideas, and absolutely no fear of being called “too much.” While glam is glittering, and the radio is still pretending it is in control, bands like Tull are selling audacity as a premium product. And here you are, holding a Made in Germany pressing on Chrysalis, with that solid green label and GEMA stamp like a little passport from the era when “complicated” still got shipped by the truckload.

How the band came to record this album

The messy truth is the fun part: the band originally tried to start a bigger project in France (yes, partly to dodge UK tax pain), but the sessions went sideways — technical problems, homesickness, and the general feeling of “why are we doing this to ourselves?” The material got binned, the clock started ticking, and Anderson had to write his way out of trouble before a U.S. tour. That pressure is all over the record. Not as panic. More like: nervous energy wearing a nice jacket.

The sound, songs, and musical direction

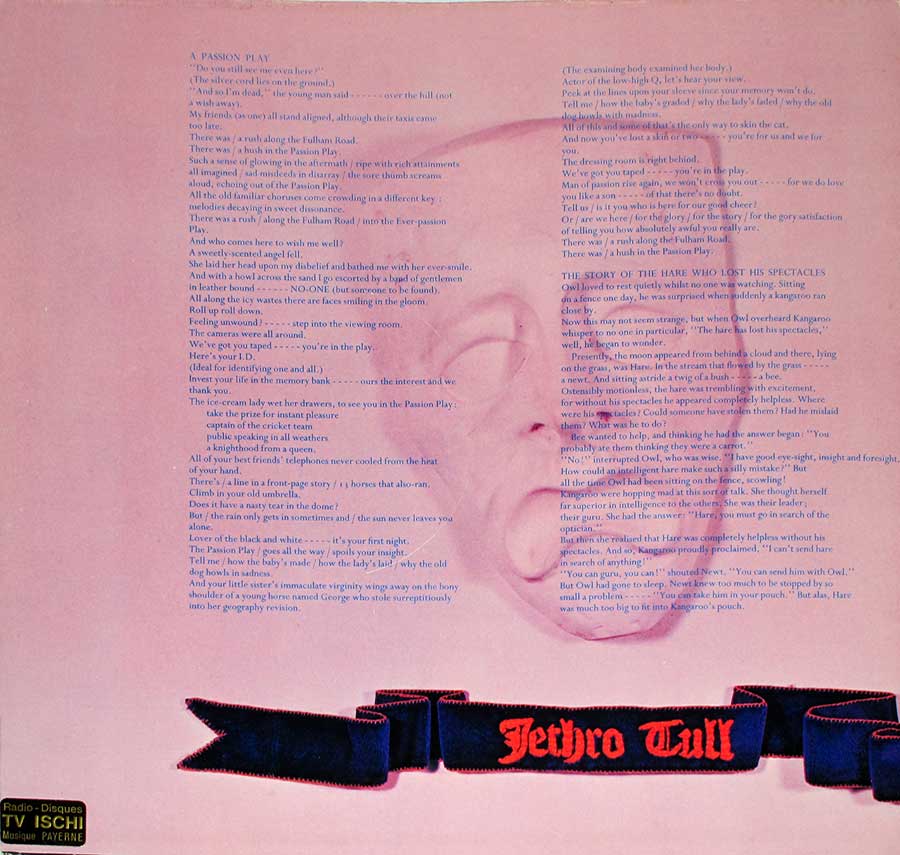

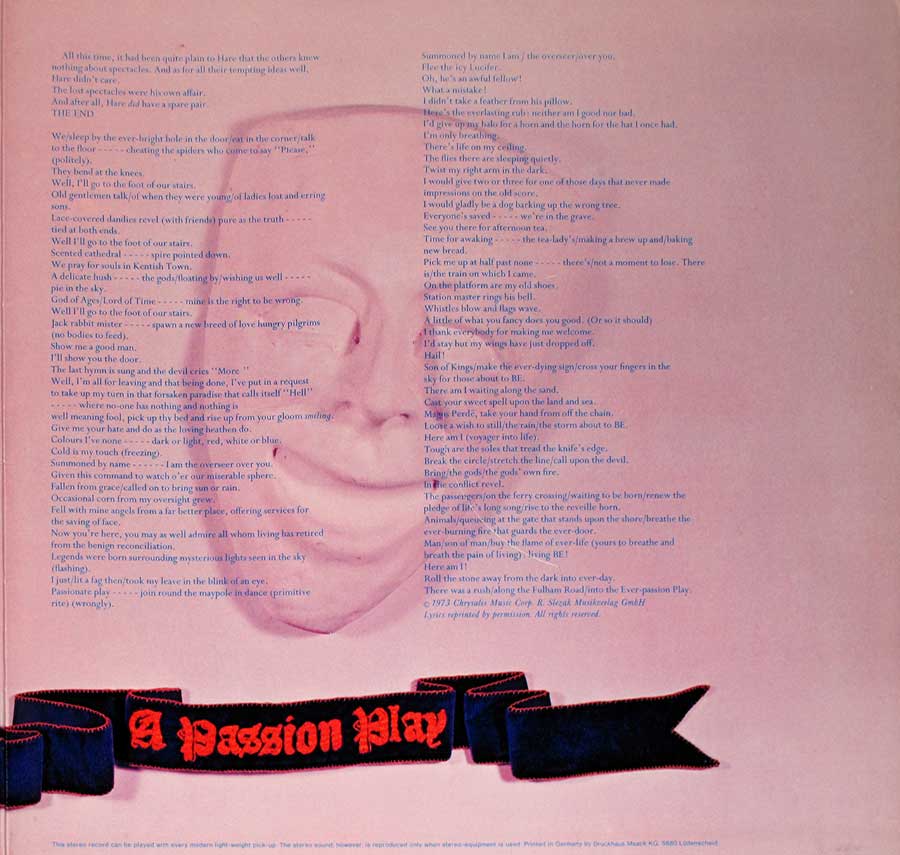

Sonically, it moves like a play with the sets changing mid-sentence. One minute you are in a delicate, almost pastoral drift, the next you are in a hard-edged riff that snaps you back to attention. “Lifebeats/Prelude” kicks the doors open, “The Silver Cord” and “Critique Oblique” stalk around with that sly, half-smirking menace, and then you hit “The Story of the Hare Who Lost His Spectacles” — narrated like a surreal children’s tale that somehow lands in the middle of your spiritual crisis. Normal? No. Memorable? Unfortunately, yes.

And then there is “10:08 to Paddington,” which feels like a quick flash of commuter reality in the middle of the cosmic fog. That is one of the album’s sneakiest tricks: it keeps yanking you between the grand metaphysical stuff and the plain human details, like it is saying, “Sure, eternity is scary — but also, you missed your train.”

Comparison to other albums in the same genre/year

If you want the 1973 prog neighborhood, it is crowded and loud in the best way.

- Pink Floyd’s "The Dark Side of the Moon" is sleek, cinematic, and engineered to hypnotize.

- Genesis’ "Selling England by the Pound" is witty, intricate, and very British about the whole thing.

- Yes’ "Tales from Topographic Oceans" is spiritual sprawl with no apologies.

"A Passion Play" does not try to be “universal.” It is pricklier than Floyd, less polite than Genesis, and more compact than Yes when Yes were in full “four sides of philosophy” mode. It is theatre, but with boots on.

Controversies or public reactions

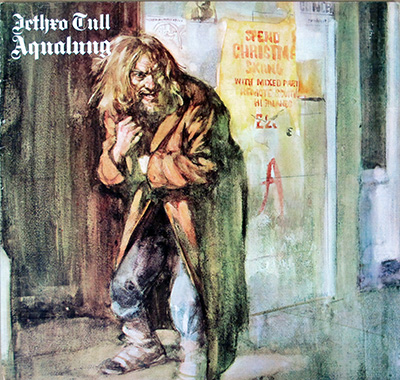

People absolutely called it pretentious and self-indulgent at the time, and I get it. It is a record that stares you in the face and dares you to blink first. Some listeners wanted another "Aqualung" moment. Others wanted "Thick As A Brick" part two. Instead they got an afterlife fable wrapped in prog gymnastics. The polite response is “mixed reviews.” The honest response is: it divided rooms.

Band dynamics and creative tensions

You can hear a band operating at peak discipline and peak stubbornness. This is not a loose jam record. It is constructed. Every transition feels chosen, rehearsed, argued over, and then locked in. Anderson’s vision is the spine, but it only works because the rest of the group can execute the weirdness without blinking. That is the tension: a strong hand on the wheel, and a band skilled enough to not crash when the road suddenly becomes a staircase.

Critical reception and legacy

Critics were rough on it early on, but the public still shoved it to No. 1 in the United States — which remains hilarious, if you think about what this album actually is. Over time it grew into a cult favorite: the record you recommend to people who say they “like prog” and then you watch their face while it plays. Decades later, it also became the kind of album that invites reissues and deep-dive mixes, because the fanbase cannot leave well enough alone. I say that with love. Mostly.

Reflective closing paragraph

This German gatefold pressing makes the whole thing feel even more like an object from another timeline — heavy in the hands, bold on the turntable, unapologetic in the speakers. "A Passion Play" is not here to make friends. It is here to make a point, and then make you sit with it. Some nights I want comfort. This is not that record. Thank god.