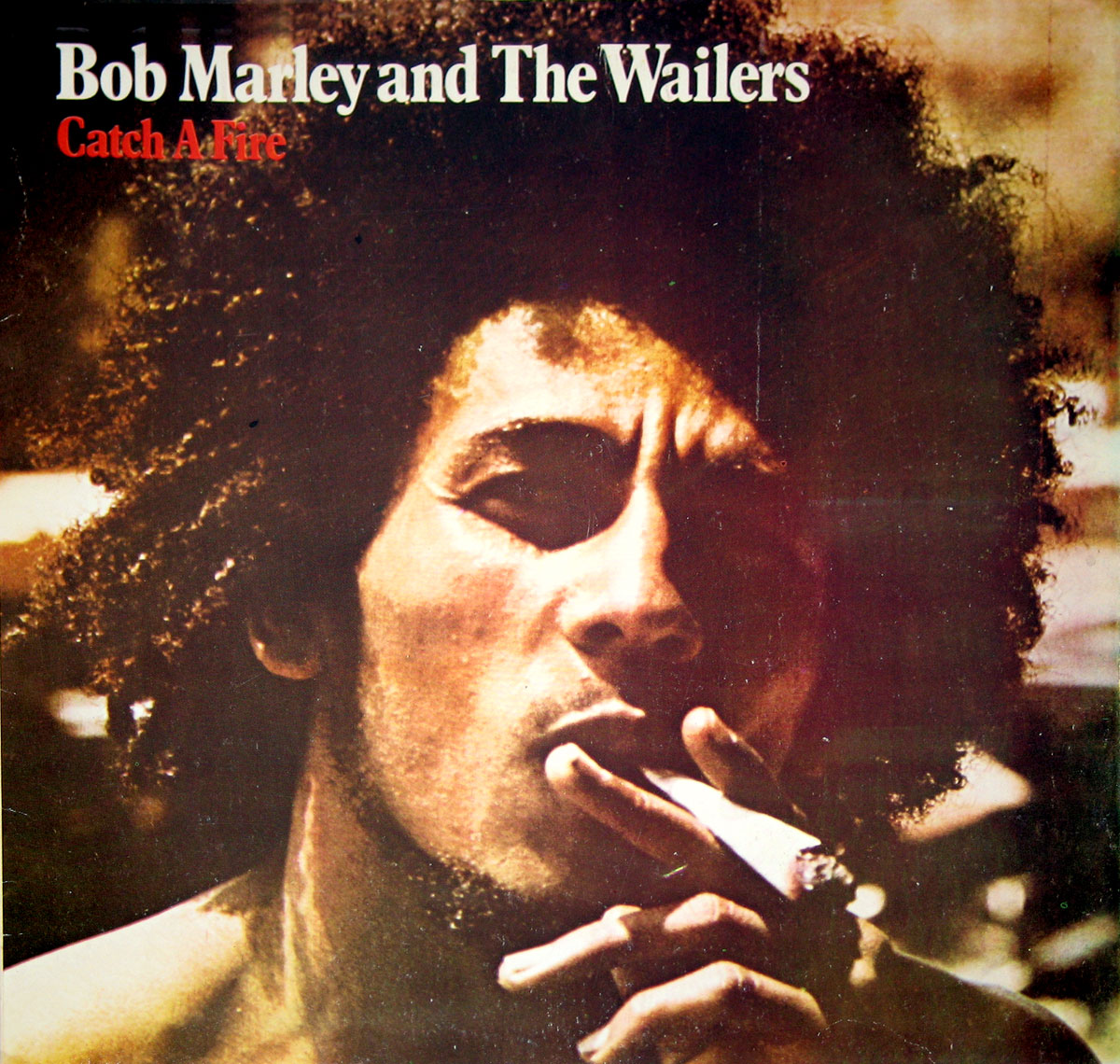

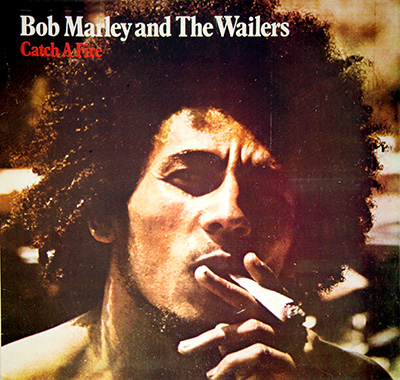

"Catch a Fire" (1973) Album Description:

On 13 April 1973, "Catch a Fire" didn’t “introduce” reggae to rock listeners. It arrived. Island even dressed it up like a Zippo lighter in the UK, like the sleeve itself was daring you to try and put it out. The Wailers sound lean and watchful: Aston “Family Man” Barrett’s bass moves slow and heavy, the guitar chops drop like a gate, and Marley sings with that calm stare people get right before they tell you the truth and walk away. You can still smell Kingston in the tape — heat, dust, nerves — and then you hear London tighten the frame just enough for the record to survive foreign turntables.

Kingston, ’72: the air feels political, even when nobody mentions politics

The basic tracks were cut across 1972 in Kingston — not in some romantic “island vibe” fog, but in working studios where time costs money and everybody knows it. The street outside was louder than any press release: arguments about power, wages, who’s getting squeezed, and who’s getting away with it. Then the early ’70s price shocks start biting, and you don’t need a textbook to understand “pressure” — you see it in the way people count cash and stretch dinner.

Sound systems weren’t background culture; they were infrastructure. A moving wall of speakers could turn a corner into a courtroom, a church, a party, and a warning — sometimes in the same night.

1973 record bins: reggae wasn’t alone — this one was just harder to ignore

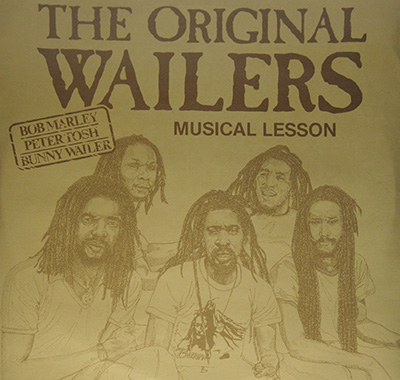

Nobody sensible thinks Marley invented reggae. The island already had voices doing different jobs, and doing them well. What "Catch a Fire" does is carry that Jamaican backbone into a package a rock label could ship without sanding off the danger.

- Toots and the Maytals came at you with gospel-soul grit — joyful, yes, but with knuckles.

- Jimmy Cliff had the leading-man glow — melody first, message right behind it.

- Burning Spear moved like a slow sermon: less “crossover,” more prophecy.

- Lee “Scratch” Perry & the Upsetters treated the studio like a haunted workshop — rhythm turned into smoke.

- Desmond Dekker still carried the earlier pop snap — lighter on its feet, built to move.

The Wailers don’t float through any of this. They march. And they don’t ask permission.

The groove: space, threat, and the slow walk that wins every time

Listen to how it breathes. Big gaps. A chop that lands clean. Then the bass shows up like a load-bearing beam you can lean your week against. Carlton Barrett doesn’t chase the song — he leans back and makes the song come to him. Patient. Slightly rude. Perfect.

“Concrete Jungle” feels boxed-in and still keeps walking. “Stir It Up” plays nice on the surface, but the rhythm section refuses to do romance without weight. “Slave Driver” doesn’t “address issues.” It points. It keeps pointing. If that makes you uncomfortable, congratulations: you’re listening properly.

Nine tracks, and somehow it still feels like a whole neighborhood talking at once.

The London fingerprints: translation, tampering, or just good sense?

Here’s the part people love to argue about when they’re feeling purist and bored. Island’s Chris Blackwell helped shape the version that crossed the water, with work done in London at Island/Basing Street alongside what was already captured in Kingston. Some additions and polishing were aimed straight at rock ears — extra clarity, extra bite, and yes, the kind of touches associated with players like Wayne Perkins (guitar) and John “Rabbit” Bundrick (keys) in the broader story around these sessions.

My take: the best moments still sound like Kingston calling the shots. The slickness never fully wins. It just puts a clean shirt on a man who’s still ready to fight.

Receipts, passports, and the price of leaving home

Once the record lands, the practical problems start multiplying: travel, promotion, who gets paid, who signs what, who “represents” whom. International success usually means somebody else is holding the receipt book. That tension isn’t trivia — it’s a low hum you can feel behind the discipline of the performances.

The band chemistry also had real-world friction built into it: not everyone even wanted the constant touring grind, and the whole operation was pulling them into rooms where the rules weren’t Jamaican rules. You can hear a group playing like time is short, because it usually is.

One small, human angle

I still hear this as a late-night record-store listen-in album: shop half-lit, somebody nursing a coffee like it’s medicine, the stylus dropping, and that bassline turning the room into a slow-moving machine. No speeches. No “importance.” Just a record doing its job while the rest of the world pretends it isn’t listening.

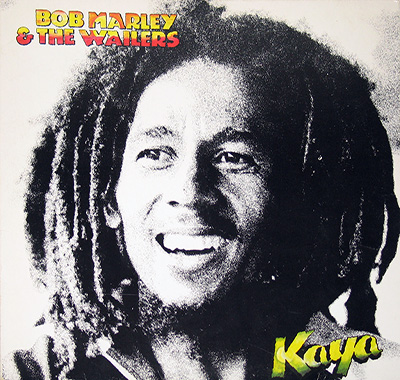

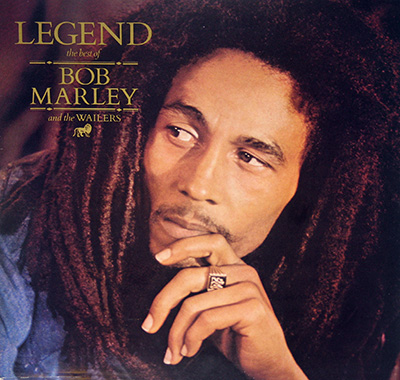

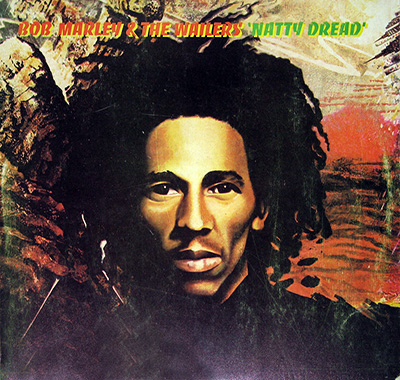

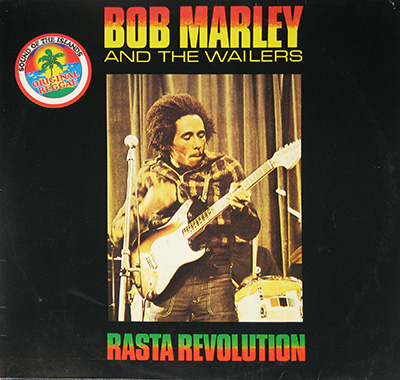

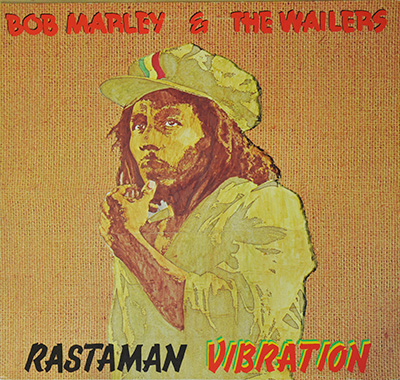

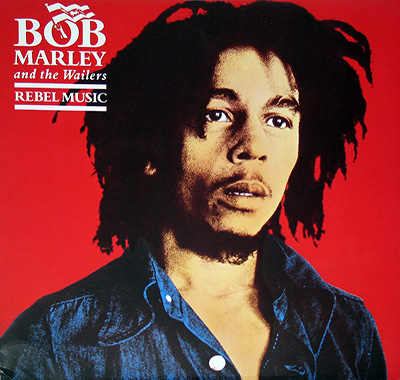

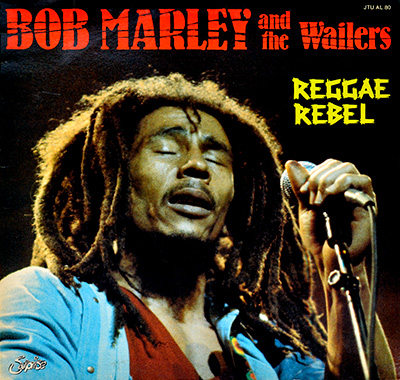

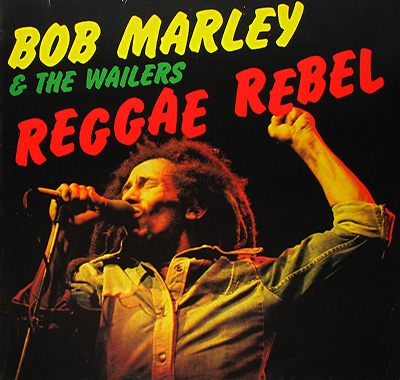

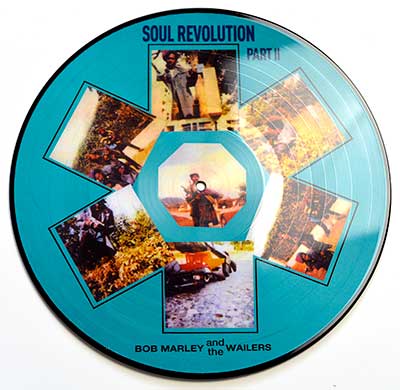

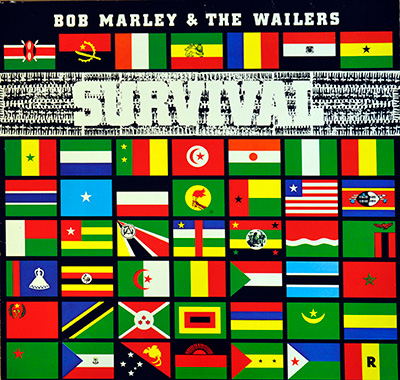

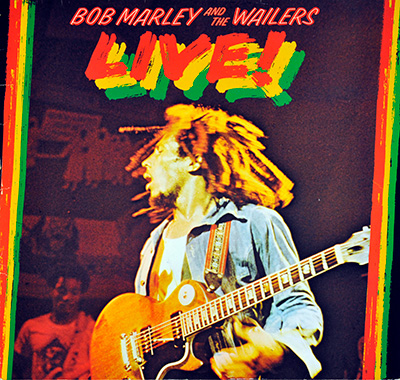

References & high-resolution cover photos

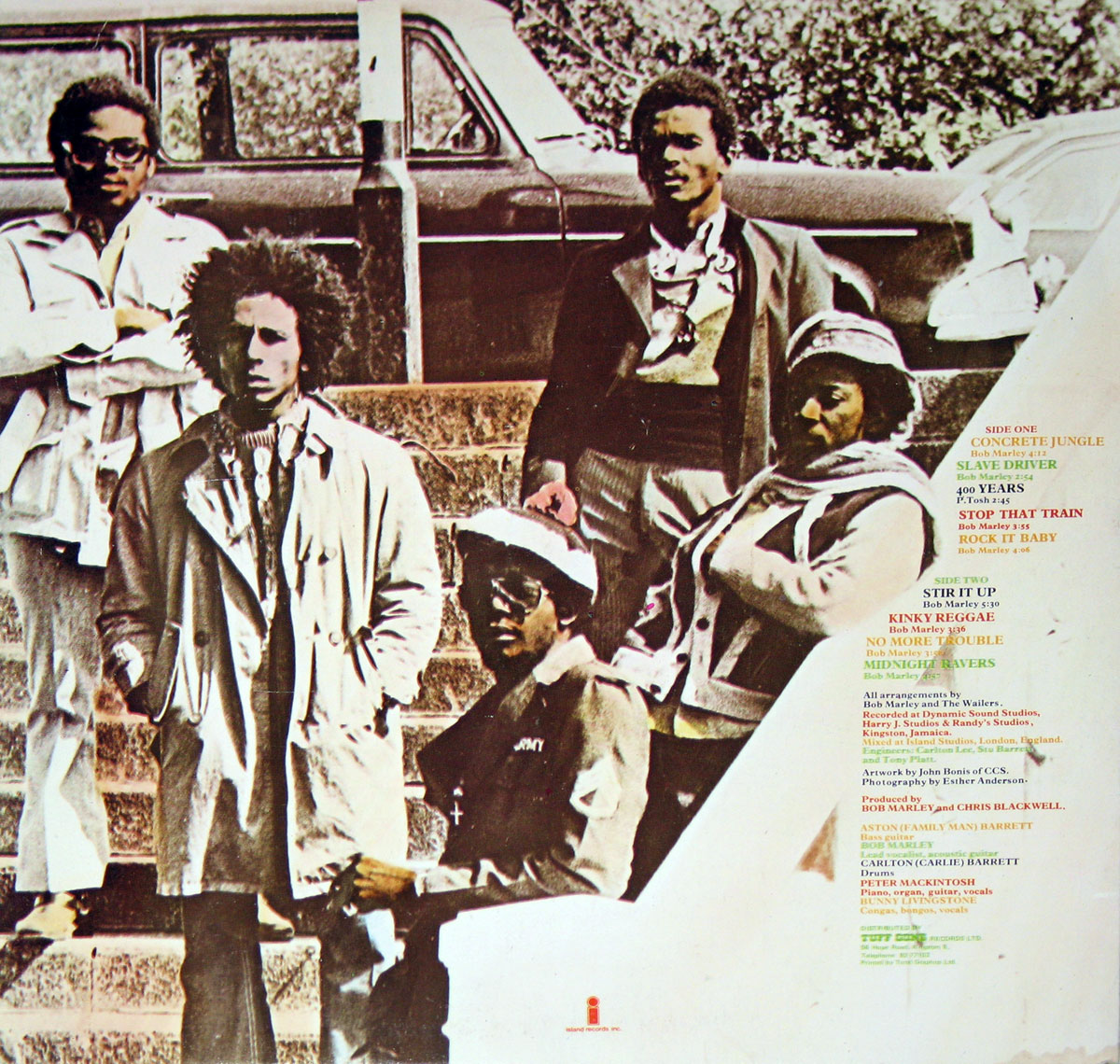

- Vinyl Records Gallery: Bob Marley & The Wailers "Catch a Fire" (high-resolution cover photos + credits)

- BobMarley.com: "Catch a Fire" (official release overview)

- Wikipedia: "Catch a Fire" (release date, recording window, personnel)

- Discogs: The Wailers – "Catch a Fire" (pressings & editions)

- The Vinyl Factory: early studio context + the overdub debate in plain English

- Basing Street Studios (Island): London hub context