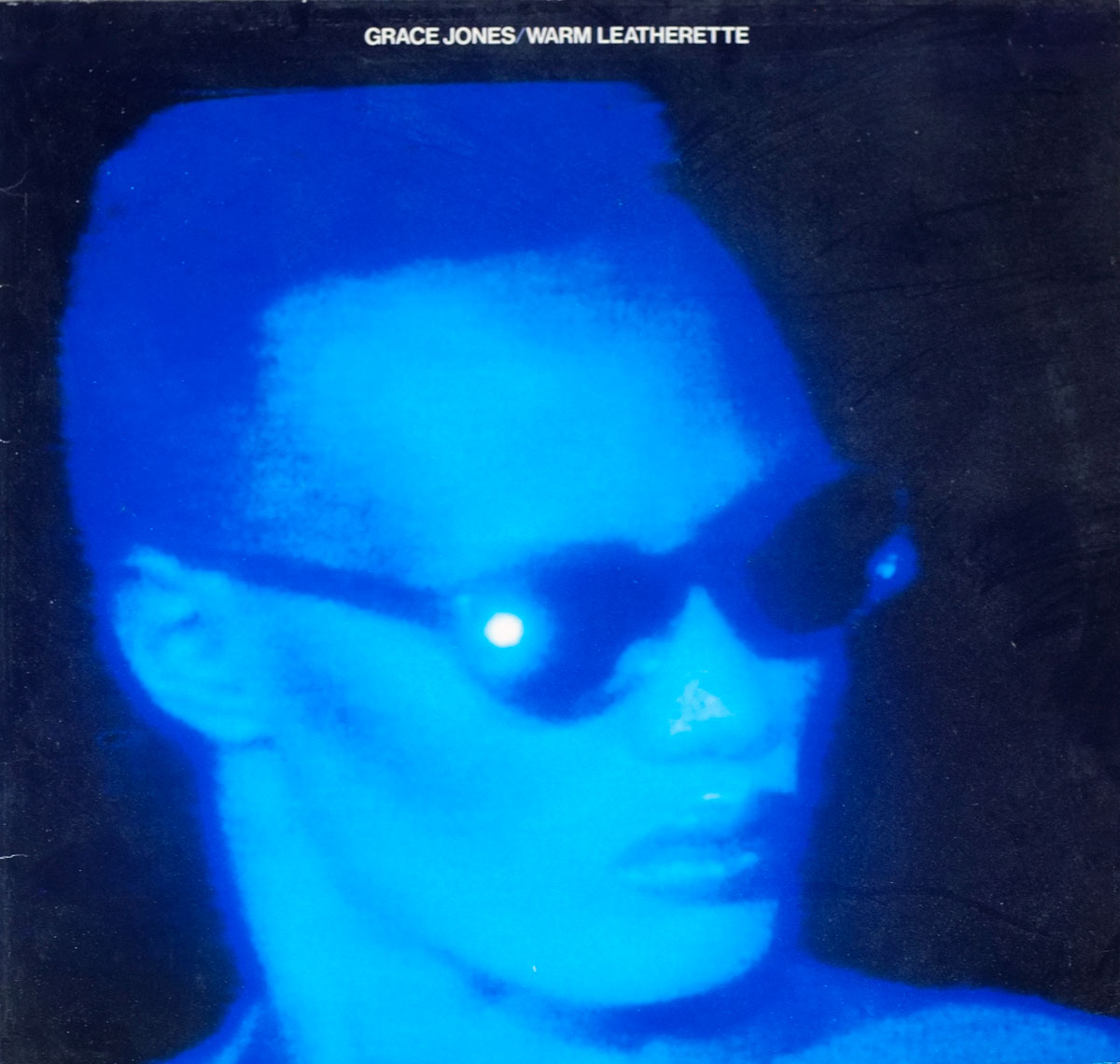

"Warm Leatherette (1980)" Album Description:

Historical Context

The year 1980 was one of turbulence and transition. Globally, the Cold War loomed with renewed intensity, while pop culture was undergoing a radical transformation. In the music world, disco had peaked and was collapsing under the weight of its own glitter. PunkÕs furious flame was already cooling, but its energy had sparked new hybrids. Out of this crucible came the icy, angular sound of New Wave and post-punkÑa genre of urgency, minimalism, and experimentation.

It was against this backdrop that Grace Jones, already infamous for her statuesque presence and nightclub notoriety, redefined herself with "Warm Leatherette." Recorded at Compass Point Studios in the Bahamas, the album declared that Jones was no longer a disco diva; she was something harder, sharper, and infinitely more dangerous.

The Music and Its Genre

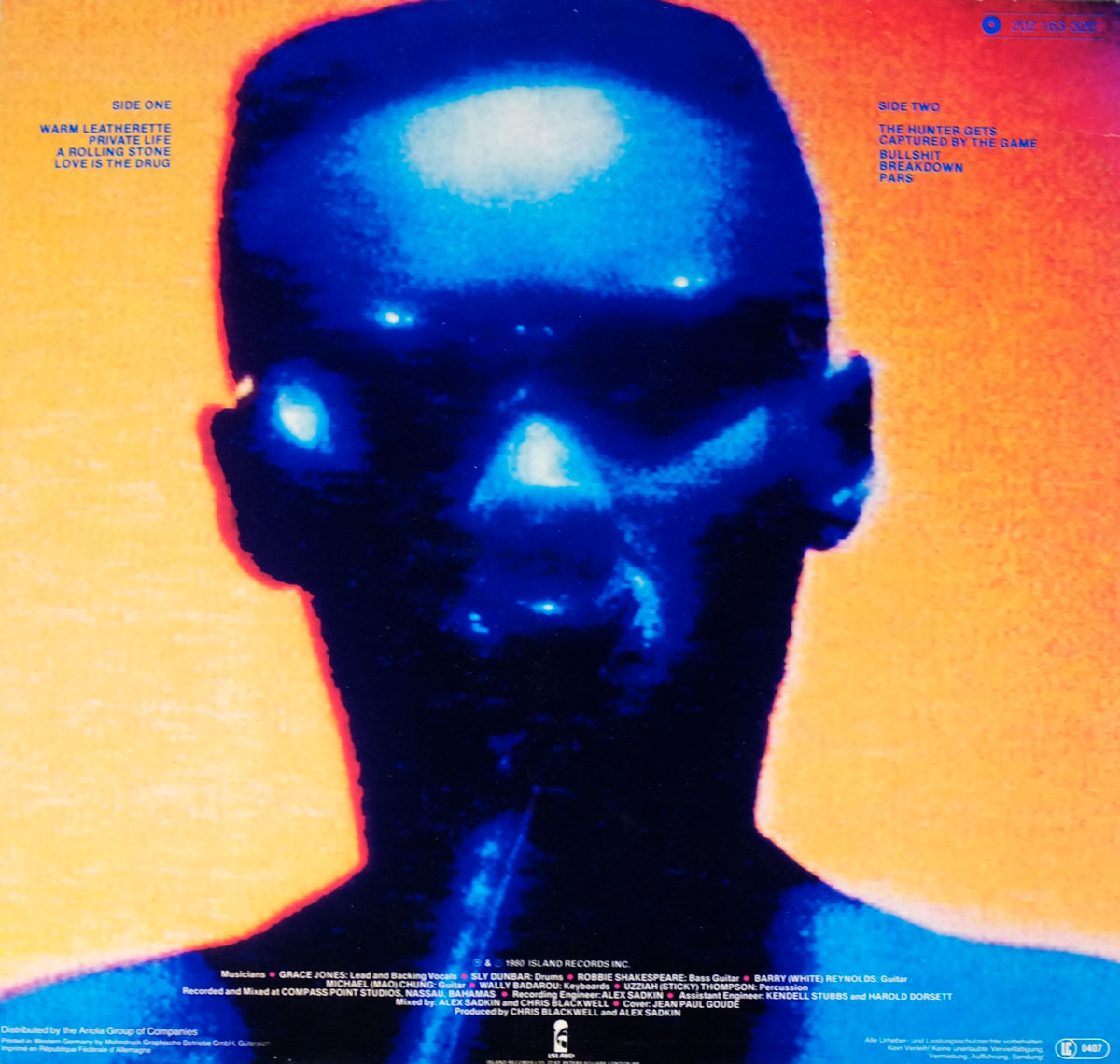

"Warm Leatherette" sits squarely in the crosshairs of New Wave meets reggae, a hybrid that was still unfamiliar to mainstream ears in 1980. New Wave, with bands like Talking Heads, Blondie, and The Police, was already chipping away at the ruins of disco, offering a soundtrack of intellectual cool and jittery rhythms. But Jones pushed further, lacing her New Wave tendencies with the heavy dub and groove of Jamaican reggae, courtesy of the rhythm duo Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare.

The result was neither comfortably pop nor strictly experimental. It was abrasive and seductive in equal measure. Covers like "Love Is the Drug" by Roxy Music and "Private Life" by The Pretenders were not simply reinterpretationsÑthey were obliterations of the originals, reassembled into harsh, robotic reggae-dub statements. It was New Wave stripped of its urban irony and rebuilt in a tropical laboratory.

Musical Exploration

What makes "Warm Leatherette" resonate is its deliberate deconstruction of familiar songs. Jones transforms pop and rock staples into alien creations, her voiceÑhalf sung, half declaimedÑdelivering lyrics with a cool detachment that suggested both command and contempt. The title track, originally by The Normal, set the tone: metallic, dangerous, and erotic in a way no disco beat could be.

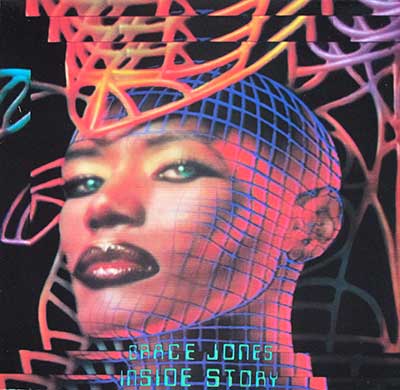

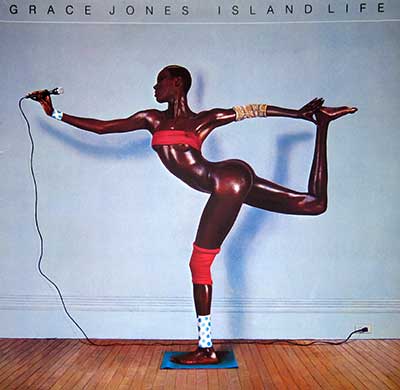

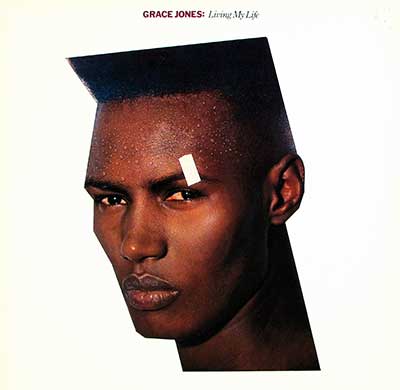

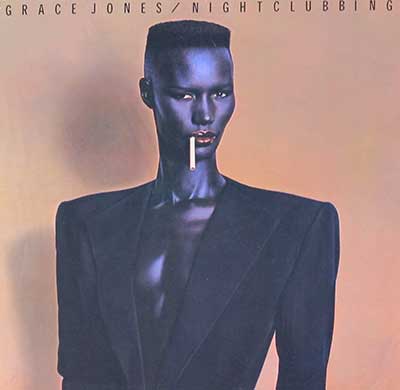

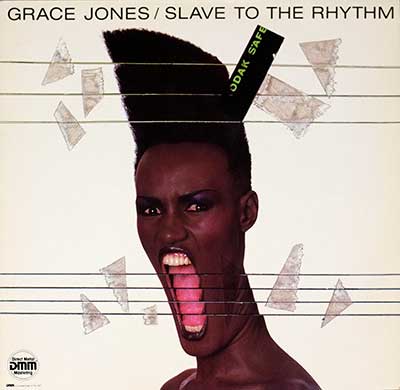

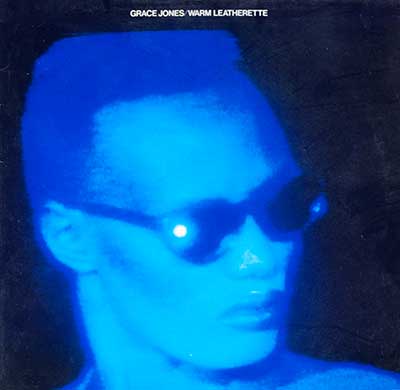

The experimentation wasnÕt only sonic but also visual. Jean-Paul GoudeÕs photography and design reshaped Jones into an androgynous cyber-sphinx. The album became a manifesto, not just a record: a statement of how music, fashion, and identity could fuse into art.

The Architects Behind the Sound

The production was helmed by Chris Blackwell of Island Records and Alex Sadkin, a studio magician who gave the album its razor-sharp edges. BlackwellÕs Compass Point Studios became the testing ground for an entire era of hybrid sound, attracting Talking Heads, U2, and Robert Palmer.

At the heart of the music were Sly Dunbar (drums) and Robbie Shakespeare (bass), whose Compass Point All Stars carved out rhythms as solid as concrete. Guitarists Barry Reynolds and Michael Chung, keyboardist Wally Badarou, and percussionist Sticky Thompson completed the cast of Caribbean craftsmen who engineered JonesÕ reinvention.

Grace JonesÕ Journey and Line-up Dynamics

Before "Warm Leatherette," Grace Jones had built her reputation on disco anthems and outrageous performances at Studio 54. But she was restless. Aligning with reggae musicians was a radical shift, effectively dissolving her old musical identity. This was no band in the traditional senseÑJones was the axis, the musicians rotated around her gravitational pull.

This fluidity in line-up underscored her approach: Jones was less a frontwoman of a band than the director of a multidisciplinary art experiment. Her collaborations were mercenary and visionary, designed to constantly reinvent rather than repeat.

Controversies and Reactions

Unsurprisingly, "Warm Leatherette" polarized critics. Traditional pop audiences found it too abrasive, too robotic, too alien. Disco purists mourned the loss of the glittering diva. But to those tuned into the post-punk wavelength, it was revolutionary. The title trackÕs references to car crashes and sexuality raised eyebrows, echoing J.G. BallardÕs dystopian obsessions. Jones herself became a lightning rod for debates about race, gender, and identity in pop cultureÑcelebrated by some as a trailblazer, dismissed by others as a provocation.

Yet, even the detractors couldnÕt ignore the impact. This wasnÕt an album made to please. It was made to shock, to seduce, to challenge. And in doing so, Grace Jones forged a path no one else dared to walk.