Grace Jones - Nightclubbing: Cold Glamour, Warm Blood, and Studio Voodoo

Grace Jones didnÕt just walk into the 1980s Ñ she stormed in with shaved eyebrows, sculptural cheekbones, and a voice that growled like a jaguar trapped in a chrome echo chamber. With Nightclubbing, released in 1981, she proved that being "ahead of your time" wasn't a compliment Ñ it was a threat.

Historical Context: From Disco Collapse to New Wave Rebirth

The glitterball had crashed. Disco was dead Ñ or so the straight white boys wanted to believe. But from the ashes of Studio 54 rose a strange, genre-bending phoenix. Enter Compass Point Studios, perched like a mirage outside Nassau, where producer Chris Blackwell and engineer Alex Sadkin started conjuring a sound that lived in no fixed nation Ñ part reggae, part rock, part dub, part machine-gun funk.

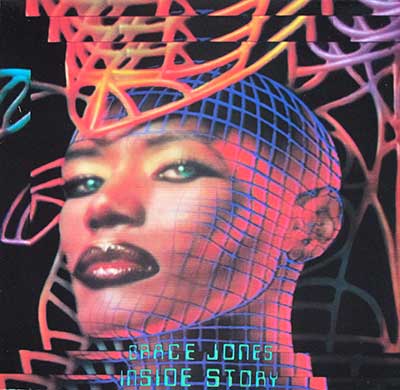

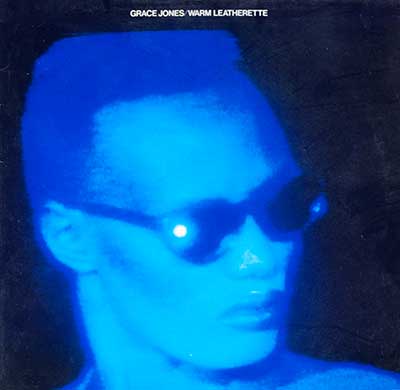

In that humid Bahamian vortex, Jones recorded the second part of what would become her iconic Compass Point Trilogy. If 1980Õs Warm Leatherette had been the rough sketch, then Nightclubbing was the oil painting: cold, polished, erotic, and paradoxically human.

Musical Exploration: Cold Steel Wrapped in Velvet Bass

Nightclubbing wasn't just a genre experiment Ñ it was a genre obliteration. The album took Iggy PopÕs sinister title track and submerged it in a slow-dub narcotic haze. Pull Up to the Bumper slyly masked raunch with innuendo and rubbery funk, while IÕve Seen That Face Before (Libertango) layered Parisian melancholy over Astor PiazzollaÕs tango, making continental dread danceable.

The band Ñ the Compass Point Allstars Ñ were no mere backing group. Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare anchored everything with telepathic timing; Wally Badarou layered synthetic textures like digital silk. Every pluck, slap, and synth ripple was minimalist and surgical, but the result felt animal and alive.

Controversies: Androgyny, Arrogance, and Apocalypse

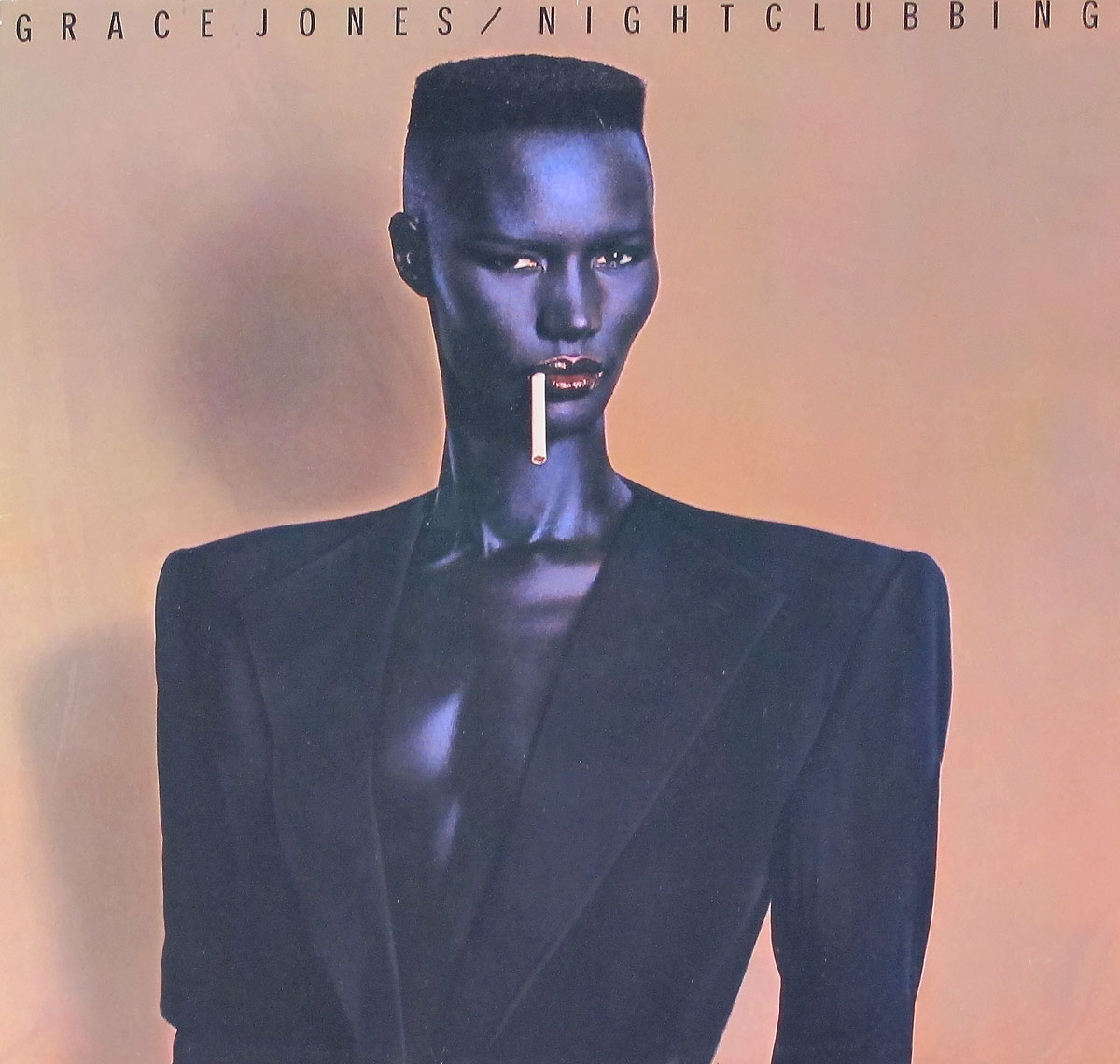

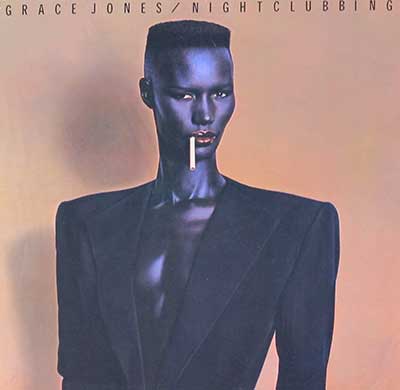

Grace Jones wasnÕt controversial by accident Ñ she was the controversy. Nightclubbing put the final nail in the coffin of traditional pop femininity. She wasnÕt soft, didnÕt coo, and never begged. She glared from the cover like a nightclub predator, not a victim.

Critics called her Òicy,Ó Òalien,Ó Òtoo masculine.Ó In reality, she was performing the gender binary into submission. The cover Ñ painted by her lover and collaborator Jean-Paul Goude Ñ became an image of queer defiance, Black futurism, and high fashion weaponized.

Grace didnÕt whisper about sexuality Ñ she bulldozed it. Songs like Feel Up and Pull Up to the Bumper dripped with innuendo that was impossible to ignore, enraging censors and delighting the dancefloor. In a Reagan-Thatcher world of corporate gloss and moral panic, she was the virus.

Recording Studio Alchemy: Compass Point's Sonic Sorcery

Compass Point wasnÕt just a studio Ñ it was a temple. Blackwell's vision was to make records in paradise with no clocks and no borders. And Nightclubbing is the most distilled result of that philosophy.

Unlike earlier Jones records, which were polished in New York studios with disco sheen, this one breathed Caribbean heat and European chill. The Bahamian humidity is in the reverb; the freedom is in the pacing. Songs stretch like shadows at dusk. Even when the BPMs are fast, the vibe remains suspended Ñ like time doesn't matter here.

Production Team: When Stylists Become Sonic Architects

Chris Blackwell and Alex Sadkin didnÕt just ÒproduceÓ Ñ they curated atmosphere. SadkinÕs engineering is ghostlike: minimal but meticulous. Basslines donÕt just rumble; they haunt. Vocals float above the mix like whispers in a cathedral.

But the real production statement was visual. Jean-Paul Goude didnÕt just style Jones Ñ he sculpted her. Her look Ñ part cyborg, part panther, part fashion oracle Ñ was inseparable from the music. The cover of Nightclubbing is more iconic than most bands' entire discographies.

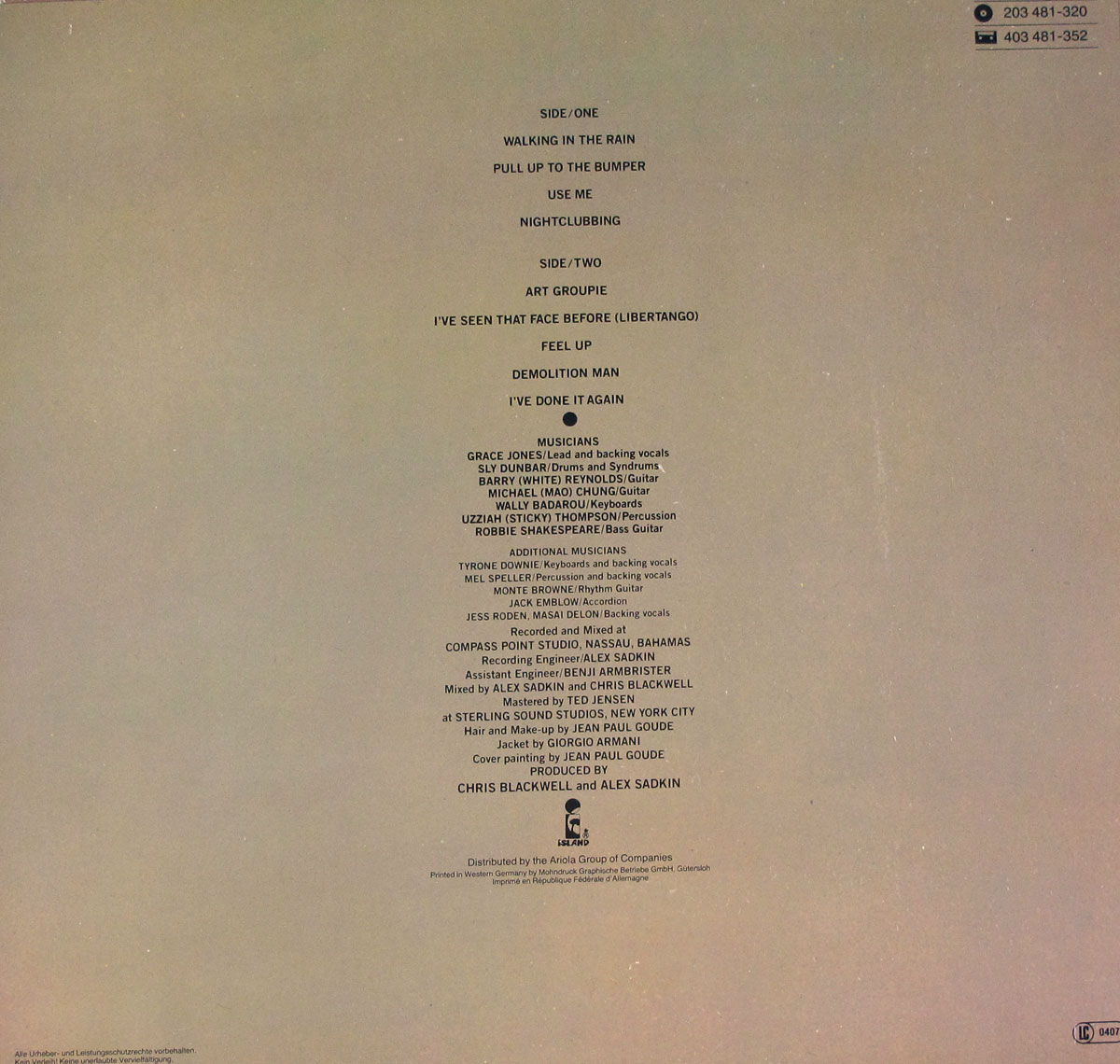

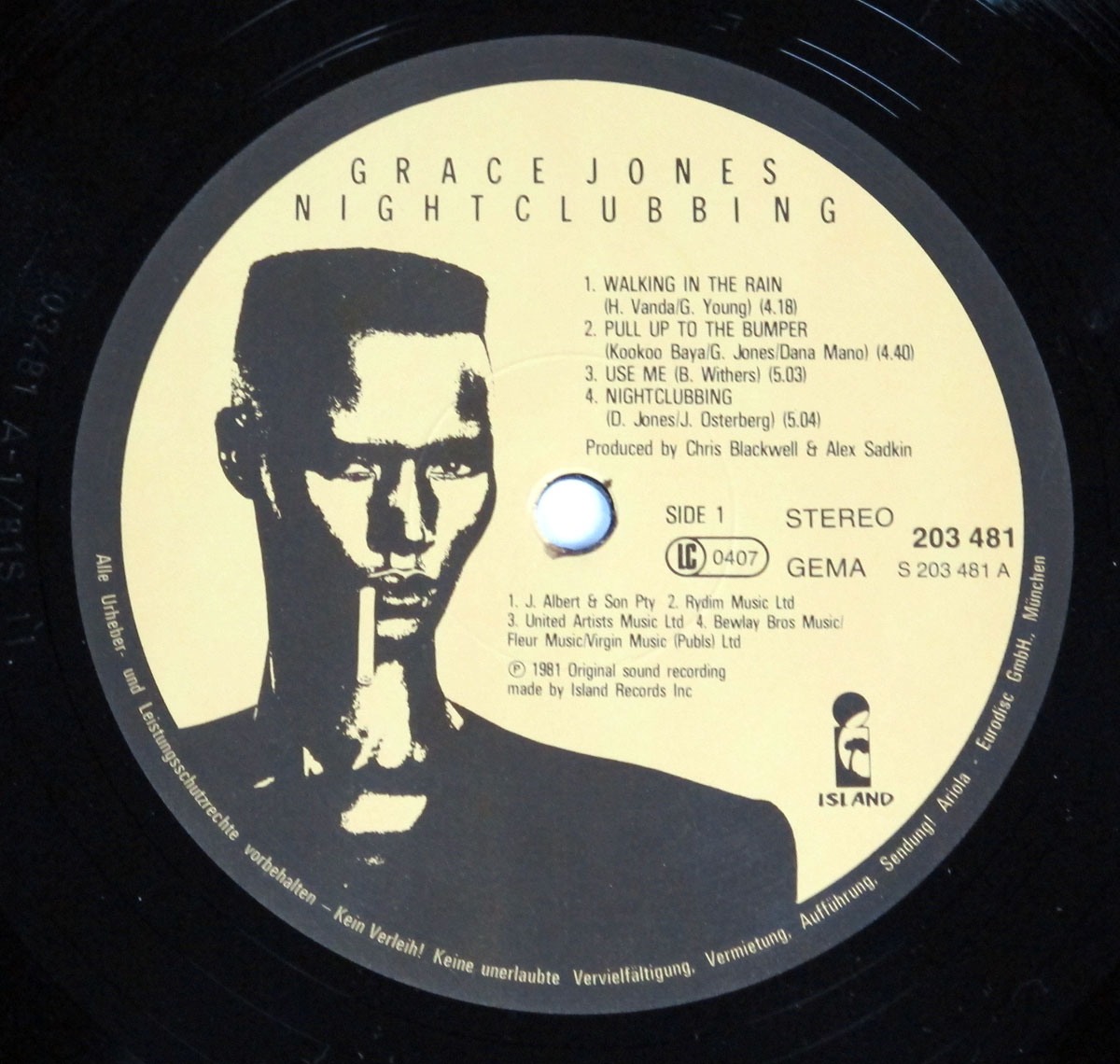

Variants and Differences: European Cold vs American Cool

The albumÕs release saw minor regional differences Ñ track ordering, label prints, and mastering. The German and Dutch pressings under IslandÕs 203 481 catalogue number often featured sturdier jackets and deeper grooves, giving audiophiles a slight edge in sound quality. Some US pressings clipped the bass, ironically neutering the albumÕs most primal weapon.

But the essence never changed: Nightclubbing wasnÕt a record you played in the background Ñ it was a confrontation.

Conclusion: A Blueprint for Pop Mutiny

Nightclubbing didnÕt follow pop Ñ it stalked it. ItÕs an album that dismantled gender, geography, and genre with predatory grace. While the industry still struggles to catch up, Grace Jones Ñ part dominatrix, part philosopher, part sci-fi construct Ñ remains not a pop star, but a myth.