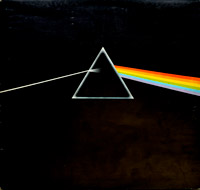

"The Dark Side of the Moon": the record that politely rewired everyone’s brain

1973: one needle drop, and suddenly pop music had to grow up

In 1973, Pink Floyd released "The Dark Side of the Moon" and basically raised the bar so high that half the rock world spent the next decade pretending they didn’t notice. This wasn’t “a bunch of songs.” It was a stitched-together experience — a full 12-inch cinematic head-trip about time, money, fear, loss, and that low-level dread we all carry around like spare change.

The first contact is physical: that heartbeat at the start of ‘Speak to Me.’ It’s not a cute intro, it’s a pulse check. The record doesn’t ask your permission; it just starts dragging you into its mood. From there, the album moves like one long thought that won’t stop circling back on itself — life as a loop, the mind as a maze, and the exit sign always flickering.

Side A barely lets you inhale. ‘Breathe’ slides into ‘On the Run’ with that nervous, forward-leaning momentum, and then ‘Time’ hits like a cold shower: clocks exploding, guitars biting, lyrics that feel like they were written by someone who looked at the calendar and didn’t like what it said. When ‘The Great Gig in the Sky’ arrives, it’s the emotional rupture — Clare Torry’s wordless vocal doesn’t “perform,” it detonates. It’s the sound of panic and acceptance shaking hands.

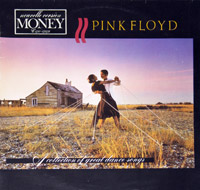

Flip the record and Side B kicks the door open with ‘Money.’ The cash register is a hook, sure, but it’s also a warning label. The groove is slick and ugly at the same time — the exact feeling of watching capitalism smile at you while picking your pocket. From there the album keeps widening: ‘Us and Them’ drifts in with that weary grandeur, ‘Any Colour You Like’ swirls and spirals, and then the closing stretch lands the philosophical punch. ‘Brain Damage’ and ‘Eclipse’ don’t just end the album — they collapse the whole theme into one last, unsettling truth: it’s all connected, and none of us are completely in control.

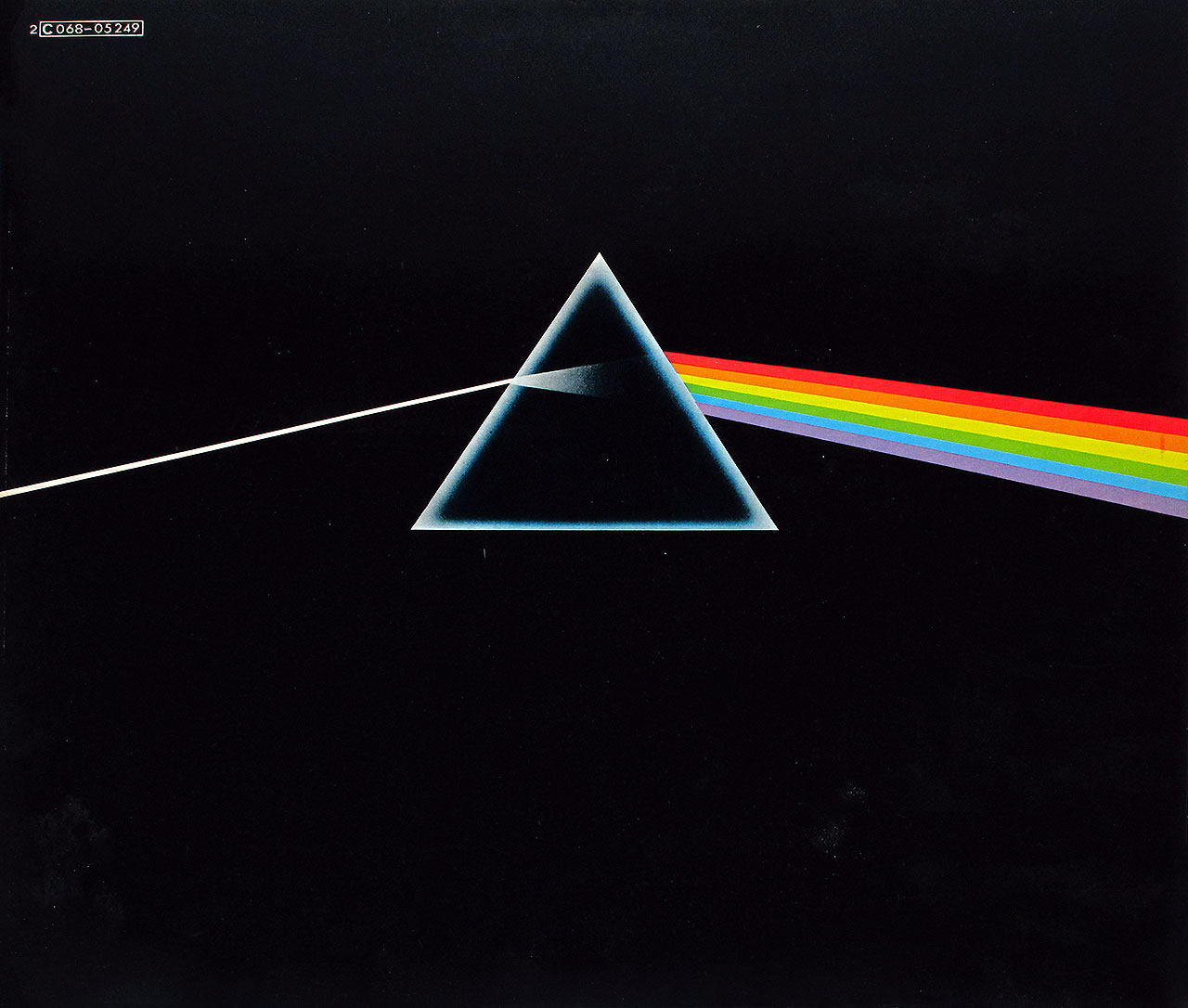

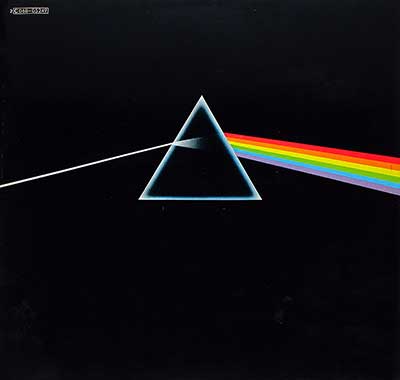

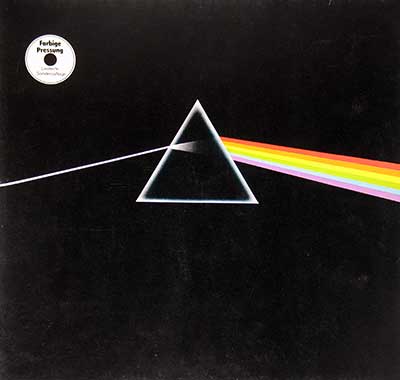

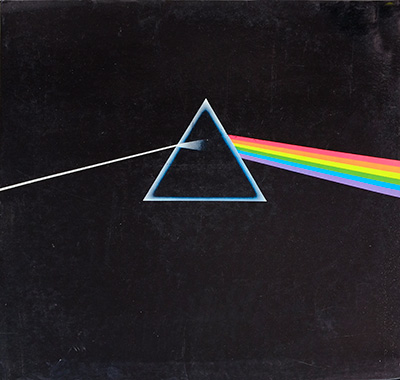

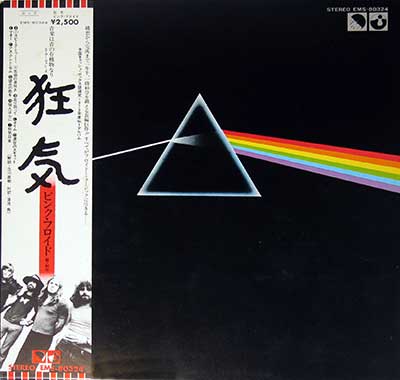

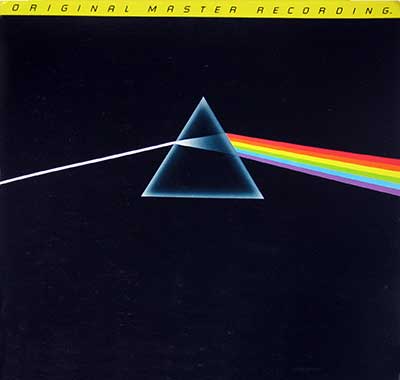

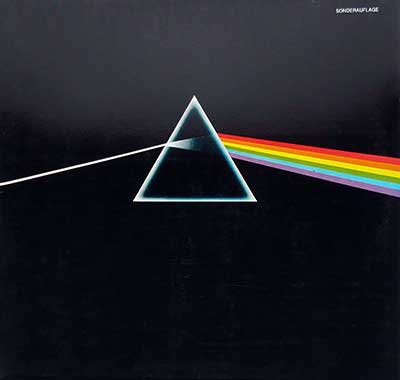

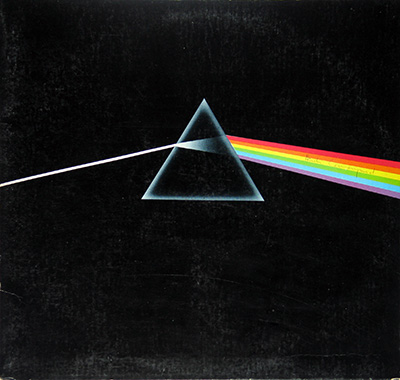

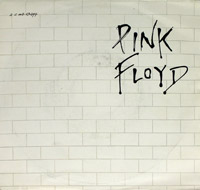

The reason this record still matters isn’t just nostalgia, or sales figures, or the fact that you’ve seen the prism on a thousand t-shirts. It’s because the album still works as a complete listen — start to finish, lights low, volume up, brain open. A playthrough on 12” vinyl isn’t “retro.” It’s a reminder that music can be a place you go, not just a thing you put on.