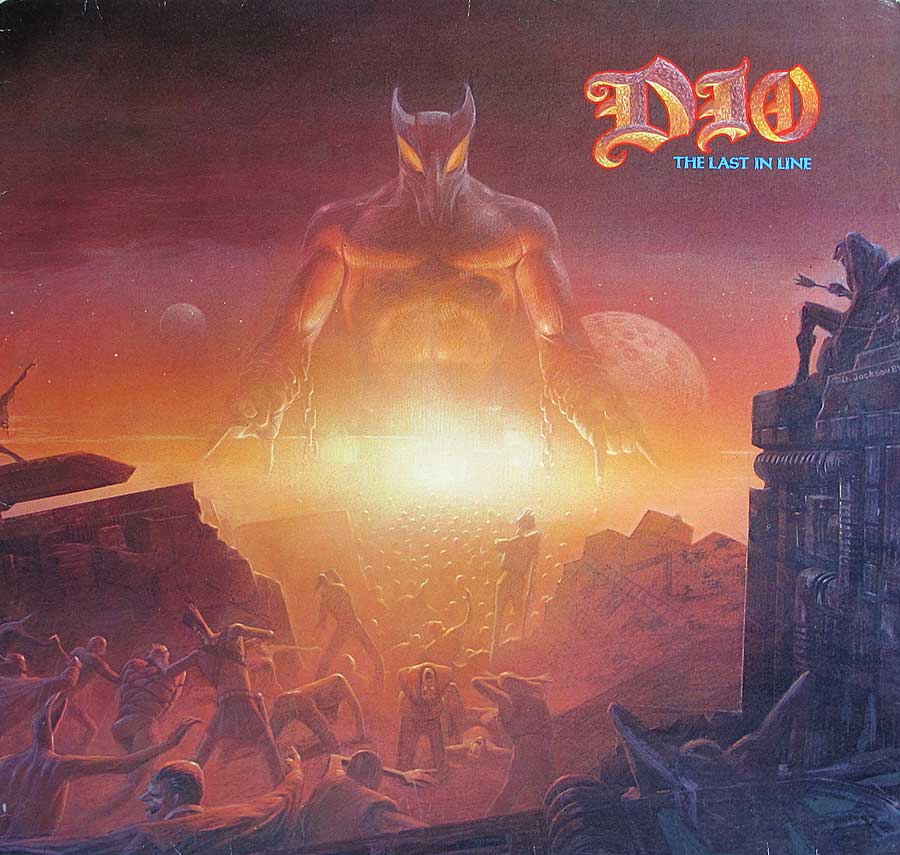

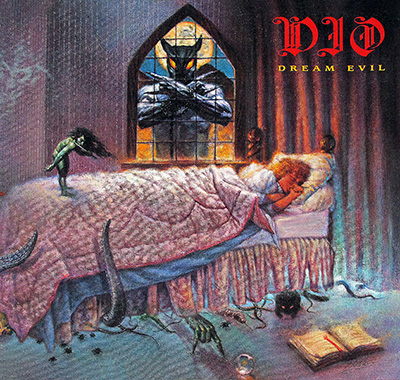

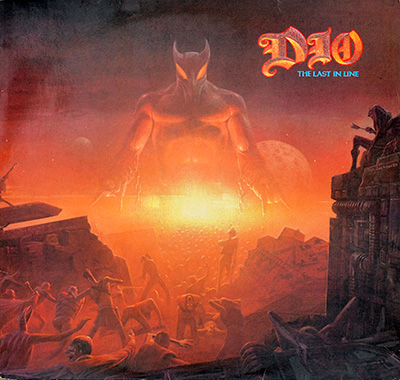

"The Last in Line" (1984) Album Description:

"The Last in Line" hits like a band that’s done being introduced. The first seconds don’t flirt, they march: a hard, clean guitar attack, drums that sound like they were tuned to intimidate, and Ronnie James Dio planting his flag where the chorus can’t miss it. This is heavy metal built for arenas, sure, but it’s not the goofy kind that winks at you from the stage; it stares straight through the fog machine and expects you to flinch first.

What 1984 felt like, and why this record didn’t apologize

1984 was noisy in a specific way: louder amps, louder hair, louder opinions, and a whole lot of people suddenly acting like heavy metal needed to justify itself. MTV was turning riffs into product, radio wanted “big” without “scary,” and every suburban parent with a worried face had discovered the thrill of being offended by album covers. That’s the air "The Last in Line" breathes in, and it doesn’t soften a single consonant to make the neighbors comfortable.

The funny part is how controlled it all is underneath the theatrics. The band sounds disciplined, not messy, not druggy, not “we’ll fix it in the mix,” and that’s where the power really comes from. Plenty of metal records in ’84 sounded like a party; this one sounds like a plan.

Where it sits in the metal zoo

Genre tags like “Heavy Metal” and “NWOBHM” get slapped on a lot of things, but here they actually explain something useful: the riffs have that British-stiff backbone, while the production punches like an American arena system. Put it next to a few peers from the same year and the differences jump out fast:

- Compared to Iron Maiden’s sprint-and-gallop approach, Dio moves slower and heavier, like every chorus is being hauled into place by winches.

- Compared to Judas Priest’s chrome-and-razor precision, this is thicker and more narrative, less machine shop, more storm warning.

- Compared to Metallica’s early thrash speed and abrasion, Dio is about weight and control, not chaos.

- Compared to the glam-metal gloss creeping into the mainstream, this record refuses to flirt. It’s not trying to date you.

How it sounds when the needle actually drops

The guitars (Vivian Campbell) are sharp without being thin, and they’re arranged like someone cared about space instead of just stacking distortion until it turned to oatmeal. Jimmy Bain’s bass doesn’t wander; it underlines, it reinforces, it makes the riffs feel like they have boots on. Vinny Appice plays with that big-room confidence, the kind of drumming that doesn’t need fancy fills because the time itself is already a threat.

Tracks like “We Rock” are built as crowd weapons, blunt on purpose, and they work because the band commits to the simplicity without turning it into a joke. The title track “The Last in Line” stretches out more, opening up a sense of movement and tension, and the chorus lands like a door being kicked in. “Egypt (The Chains Are On)” is the one that leans hardest into atmosphere, but it keeps muscle in the frame; the mood never gets to replace the riff.

Dio’s voice is the headline act, obviously, but the trick is how it sits inside the band instead of floating above it. He doesn’t sound “mixed loud” so much as “built into the structure,” like the songs were written around the shape of his phrasing. That’s a practical advantage, not a mystical one.

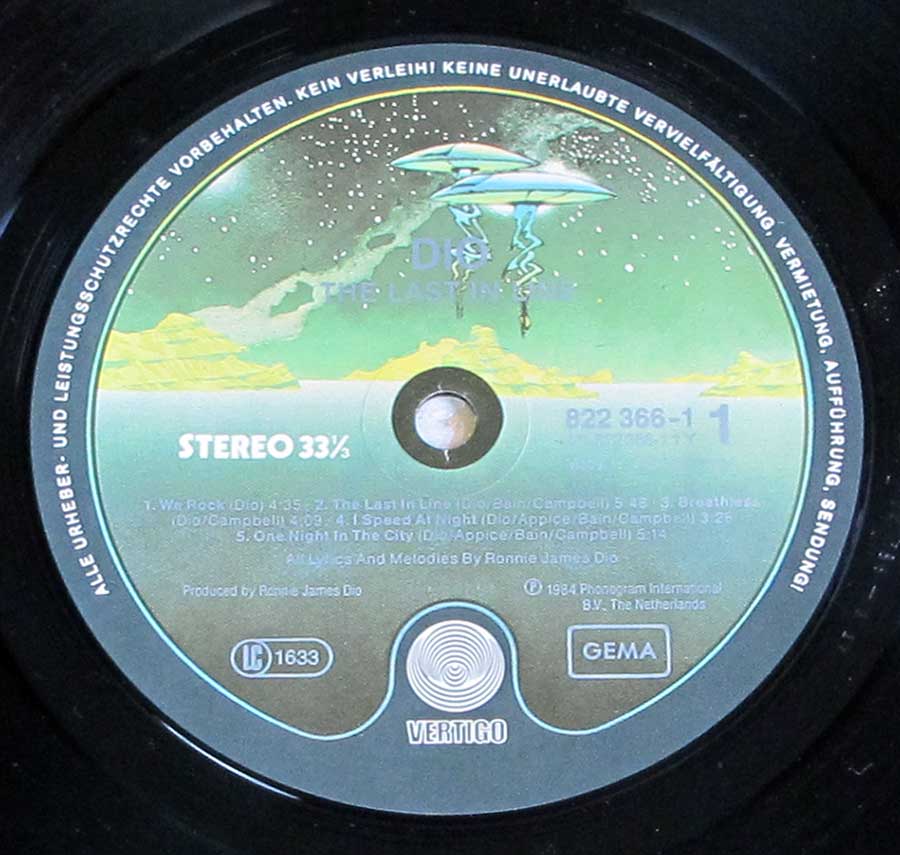

The people behind the sound, and what they actually did

The back cover spells it out: produced by Ronnie James Dio, engineered by Angelo Arcuri with Rich Markowitz assisting, recorded at Caribou Ranch, and originally mastered by George Marino at Sterling Sound in New York. Those aren’t decorative credits. The sound here is big but controlled, which usually means somebody in the room kept saying “again” until the performance locked, then somebody at the desk refused to let the low end smear into the guitars.

Claude Schnell’s keyboards are the quiet leverage point. He isn’t there to turn the band into prog, he’s there to widen the room and thicken the shadows, especially when the arrangements need to feel larger than five people. It’s subtle in the way subtle things are always accused of “not doing anything” by people who don’t listen carefully.

Band chemistry as cause and effect

This lineup feels like a machine built out of personalities that could have clashed if they weren’t aimed in the same direction. Dio writes like a storyteller who also understands setlists, Campbell plays like he’s trying to make every riff memorable without turning it into a jingle, and Appice keeps the whole thing from floating away into fantasy mist. The result is metal that sounds theatrical while still hitting like something physical.

A lot of bands talk about “tightening up” after a breakthrough. Here, it’s audible. The arrangements feel more deliberate, the pacing more controlled, and the big moments are placed where they do the most damage.

Controversy, or the lack of it

No single scandal trails this album like a tin can on a wedding car. The “controversy,” if you want to call it that, mostly lives in the era’s lazy habit of treating fantasy imagery and dramatic lyrics as evidence of something sinister, as if metaphor was a crime scene. The real misconception is simpler: that Dio was all castles and capes. Records like this one are built on rhythm, tone, and pressure, and the fantasy is just the paint job.

One small, real-life anchor

Late-night radio was where this album made the most sense, when the DJ didn’t over-talk the intro and the room was quiet enough to feel the drum hits in your chest. A record shop bin in ’84 would have filed it under “metal,” but you could tell from ten feet away it was filed under “confidence.”

References

- Vinyl Records Gallery page: DIO "The Last in Line" (full photo set and page context)

- Dio (band) overview (lineup context and discography)

- Vertigo Records label background (label context)

- George Marino (mastering engineer) background

- Sterling Sound (mastering studio)

- Caribou Ranch (recording studio)

- Dio - "The Last in Line" (Official Music Video)

- Dio - "Egypt (The Chains Are On)" (Official Video)