The Belo Horizonte Blitz: A Sepultura Retrospective

There was a stretch when Belo Horizonte meant one thing to me: noise with bad intentions. Not scenery. Not postcards. Not civic pride. Just that filthy early Sepultura racket crawling out of Brazil like it had chewed through the wall to get here.

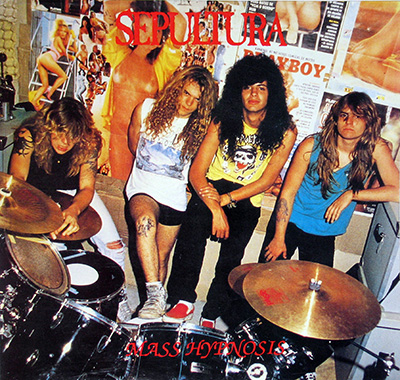

In 1984, Max and Igor Cavalera were not building a legacy. They were kids with imported records, cheap gear, no patience, and a taste for extremes. You can hear the theft in the best sense of the word: Motörhead's speed, Venom's ugliness, hardcore's blunt trauma. But it never sounds borrowed for long. On the 1985 split Bestial Devastation, shared with Overdose, Sepultura already sounded like they were playing from inside a rusted oil drum. The thing is half-performance, half-accident. I still like it for that reason. It doesn't ask permission, and it sure as hell doesn't sparkle.

Morbid Visions followed in 1986, and no, it is not some perfectly formed masterpiece hiding in the basement. The production is thin, the playing can feel like it is sprinting downhill, and that is exactly why it lives. You can hear a band pushing past imitation even while the seams are showing. Early Sepultura still had plenty of Satan, death, blasphemy and teenage bad ideas in the lyrics. Good. That mess was part of the climate. Sanding it down into a neat origin story misses the whole rotten charm.

By the time Arise landed in 1991, the room had changed. The songs hit harder because they were tighter, not because they were polite. "Dead Embryonic Cells" still feels like being shoved down a concrete stairwell by someone wearing combat boots. Igor's drumming on that record is ridiculous in the best way; not tasteful, not restrained, not designed for jazz-club approval. Just violent and exact. I remember staring at that cover in a plastic jewel case under lousy shop lighting, thinking this was what serious metal looked like when it stopped posing and got mean.

The real turn, though, was Chaos A.D. in 1993. That was the moment they quit chasing speed for its own sake and learned the power of drag, weight, and repetition. The riffs stopped racing and started marching. You felt them in the legs first. The politics also came into sharper focus there, and it did not sound borrowed from pamphlets. It sounded lived near. Corruption, violence, pressure, control. Sepultura were no longer just the wild Brazilian extreme-metal band; they had figured out how to make the groove itself sound confrontational. Some fans still wanted Arise with a fresh coat of paint. I never did. Chaos A.D. was the smarter move, and the heavier one.

Then Roots arrived in 1996 and split the room in the most interesting way. The band went deeper into Brazilian rhythm and texture, worked with Carlinhos Brown, and travelled to the Xavante to bring something real and specific into the record rather than slapping a fake "tribal" sticker on the sleeve and calling it culture. That album still sounds like collision: down-tuned guitars, hand percussion, chants, groove, dust, heat. Not subtle. Not especially tidy. Better that way.

And then it broke. Dana Wells died in August 1996. The management fight that followed did not feel like ordinary business friction; it felt like grief with knives out. Max Cavalera left later that year, and the classic line-up was done. His last show with Sepultura was at Brixton Academy in December 1996, which now sits in memory like a door slamming somewhere down the hall. Derrick Green helped the band keep moving, and there is good music in that later catalogue, but the old run from Morbid Visions to Roots still carries the smell of danger. That is the era people argue about because it earned the argument. Metal has produced bigger bands since. I am not convinced it has produced many that felt more alive.