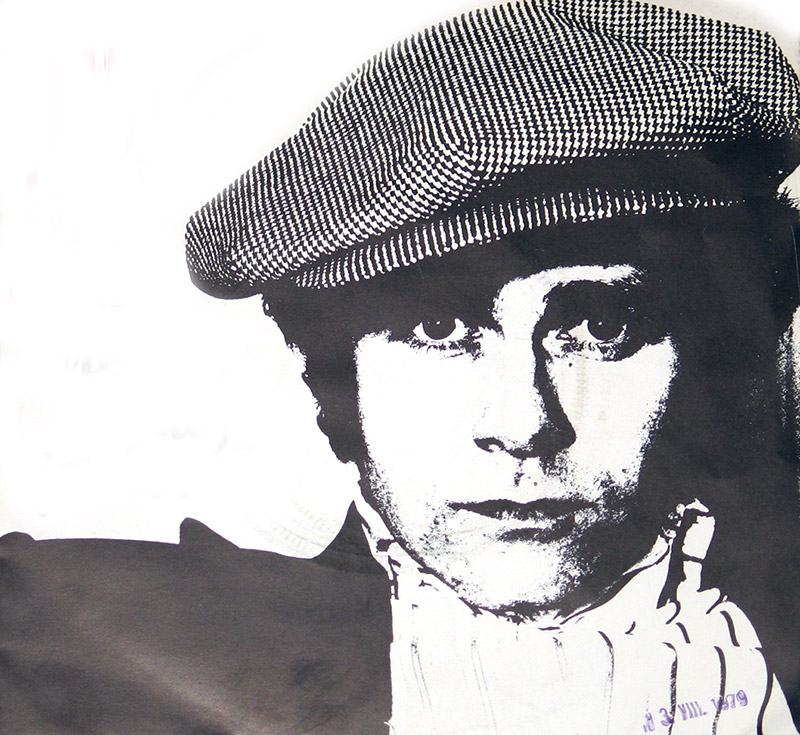

ELTON JOHN Elton John: The Piano, the Glitter

Elton John started life as Reginald Kenneth Dwight (born 25 March 1947 in Pinner, then Middlesex). Pinner sounds like a place designed to keep excitement out. The piano didn’t get that memo. Family stories and early biographies all circle the same odd detail: he was drawn to the instrument almost absurdly young, as if it was a magnet and his hands were metal.

At eleven he won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music, which is a very polite sentence for a very unpolite reality: Saturday mornings spent doing serious lessons while the rest of the world did normal kid things. You can almost hear the clash already—formal training on one side, the itch for pop and rhythm & blues on the other. That itch usually wins.

By his teens he was earning his keep as a pub pianist—Northwood Hills Hotel gets mentioned for a reason—playing standards, soaking up the room, learning what makes people look up from their drinks. Not “developing his style.” Working. Night after night. The kind of grind that teaches you timing and stamina faster than any lecture hall ever could.

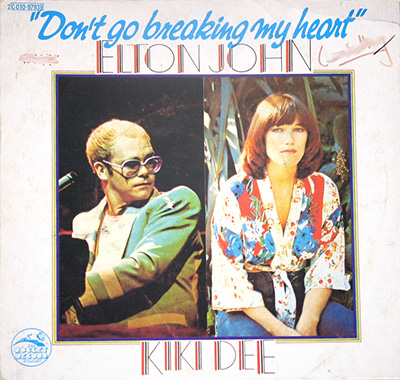

Then comes Bluesology in the early-to-mid 1960s: a band built for stages that smelled like stale beer and electrical heat. They backed touring soul and R&B acts, and later became Long John Baldry’s support band. If you want the origin story of “Elton John,” it’s right there—he stitched it together from saxophonist Elton Dean and Baldry’s “John.” Not mystical. Just practical. A better name for a bigger sound.

The real hinge point lands in 1967, and it’s basically paperwork and chance. Liberty Records (via A&R man Ray Williams) ran an ad in the NME. Reg Dwight answered it. Bernie Taupin answered it too. Neither “won” the audition the way pop mythology likes to pretend, but Elton was handed Bernie’s lyrics and told, essentially: see what you can do with this. That’s the start of one of the strangest, most durable partnerships in pop—Taupin writing words, Elton turning them into something you can’t un-hear.

His debut album “Empty Sky” arrived on 6 June 1969. It didn’t detonate the charts, and honestly, good—early records like that are supposed to sound hungry, a little cramped, like someone testing the walls. The big public “hello” comes with “Elton John” (1970) and “Your Song,” which doesn’t kick the door down so much as it quietly rearranges the furniture and pretends it was always there.

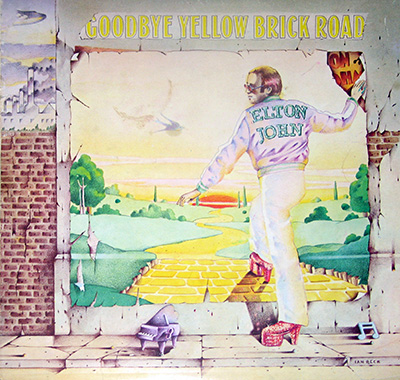

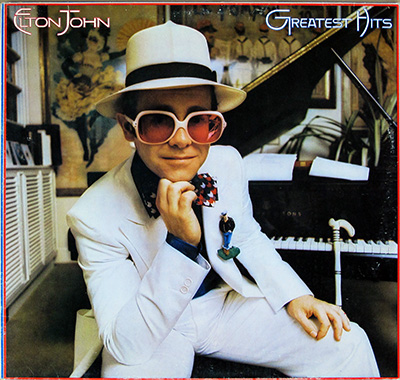

After that, the 1970s become a blur of albums that hit like postcards from different versions of the same restless brain: “Madman Across the Water,” “Honky Chateau,” “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road.” The piano doesn’t sit politely in the mix—it drives. And the clothes? Ridiculous. Gloriously, stubbornly ridiculous. People love to laugh at the sequins and platform shoes, but that flamboyance was also a weapon: a way to make sure nobody looked away.

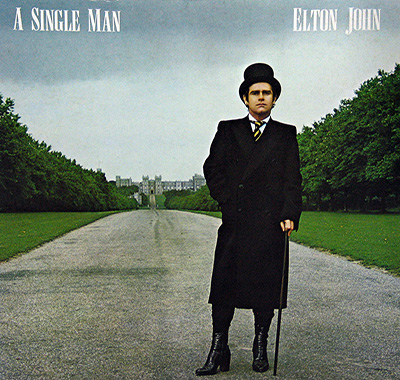

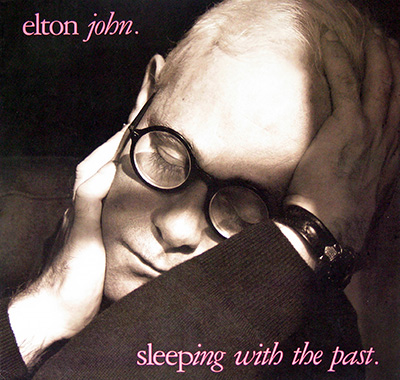

The darker part isn’t a footnote, so I’m not treating it like one. Addiction and chaos crept in, and you can hear the strain in the story around the music—relationships, health, the constant pressure to stay “on.” He got sober in 1990, and whatever else anyone thinks about celebrity redemption arcs, that one matters because it stuck.

One correction, because the internet loves a dramatic “final concert” myth: he didn’t retire in 1976, and he didn’t stage a definitive goodbye at Wembley Stadium like a Victorian farewell letter. On 3 November 1977, at Wembley Empire Pool (now Wembley Arena), he announced he was stepping back from touring. He came back, of course. People like this don’t really stop. They slam the lid, walk off, then wander back because the silence is worse.