UFO – Mechanix (1982): Rewiring British Hard Rock for a New Decade

When UFO released Mechanix in 1982, the British hard rock scene stood at a crossroads. The New Wave of British Heavy Metal (NWOBHM) was roaring through the clubs, redefining the sound that UFO themselves had helped inspire a decade earlier. Bands like Iron Maiden, Saxon, and Def Leppard were surging with youthful aggression, while the veterans of the 1970s were forced to adapt or fade into memory. For UFO, who had already lived through a dozen transformations, Mechanix was both a survival instinct and a statement of identity — a reaffirmation of their place in hard rock’s evolving machinery.

The Early 1980s: Hard Rock in Flux

The early 1980s were years of transformation. The rise of MTV and the digitization of sound recording were changing how rock bands presented themselves. While the punks of the late ’70s had shaken the establishment, by 1982, heavy rock had returned to the forefront — more technical, more polished, but still carrying the same raw energy.

In the UK, Motörhead blurred the line between punk and metal; in the US, Van Halen had ignited a revolution in guitar showmanship. Amid these movements, UFO’s challenge was to remain relevant without losing the soulful grit that defined their earlier classics like Lights Out and Obsession.

Formation and Evolution of UFO

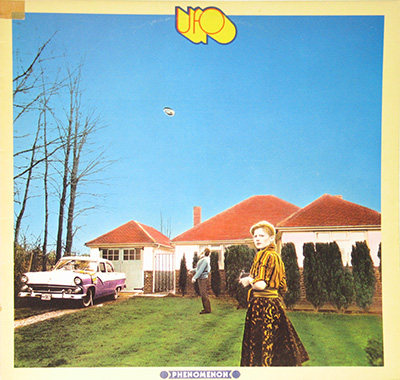

UFO’s story begins in 1968 London, when vocalist Phil Mogg, bassist Pete Way, guitarist Mick Bolton, and drummer Andy Parker formed a blues-influenced space-rock outfit. Their first two albums leaned toward psychedelic experimentation, but it was with the arrival of German guitar prodigy Michael Schenker in 1973 that UFO truly found their sound. The Schenker years yielded a series of now-iconic albums — Phenomenon (1974), Force It (1975), and Lights Out (1977) — blending melodic finesse with guitar-driven ferocity.

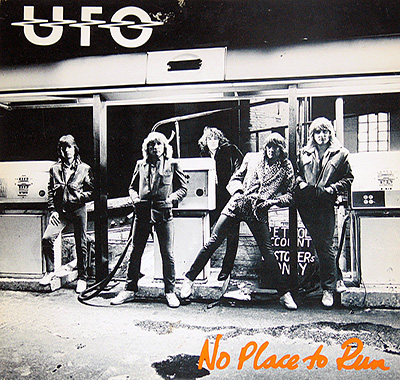

However, the constant touring, internal tensions, and Schenker’s mercurial temperament led to repeated departures. By the dawn of the 1980s, guitarist Paul Chapman had become the new lead guitarist, having filled in for Schenker before. This new lineup — Mogg, Way, Chapman, Neil Carter on keyboards and guitar, and Parker on drums — would steer UFO into the polished yet punchy territory that defined Mechanix.

Creating “Mechanix”: The Studio Process

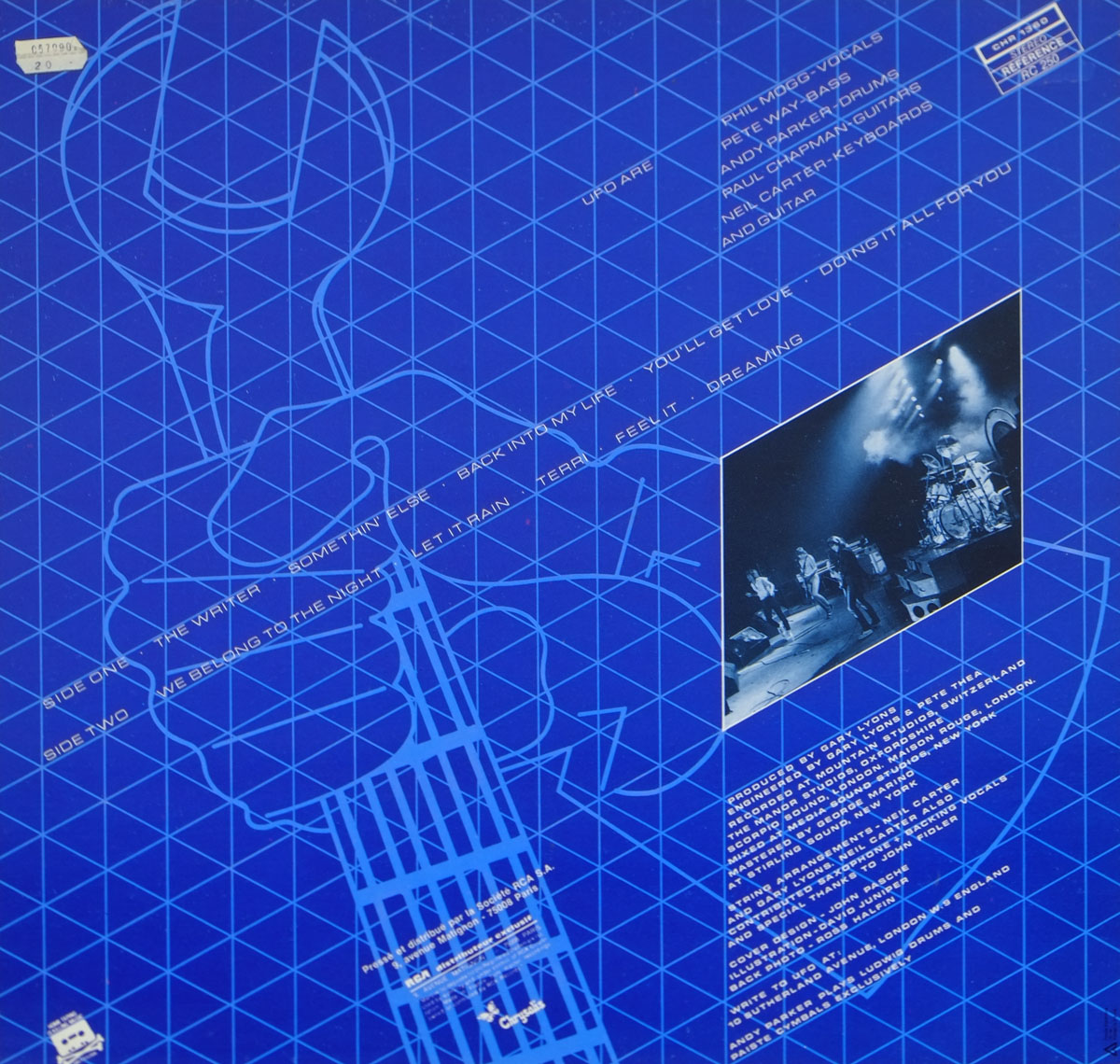

Recorded across several studios — Mountain Studios in Switzerland, The Manor in Oxfordshire, and Maison Rouge and Scorpio Sound in London — Mechanix was produced by Gary Lyons, whose previous work with bands like Foreigner had honed his ability to capture both clarity and power. The album’s mix was completed at Media Sound Studios in New York and mastered by George Marino at Sterling Sound, ensuring a transatlantic finish worthy of its ambitions.

Lyons encouraged the band to experiment with tighter arrangements and melodic layering. The result was a record that balanced the grit of traditional hard rock with the slicker production values of the early ’80s. Songs like “The Writer” and “We Belong to the Night” showcased UFO’s ability to merge muscular riffs with radio-ready hooks, while “Let It Rain” hinted at the atmospheric depth that Carter’s keyboards brought to the table.

Sound and Musical Exploration

Mechanix isn’t a concept album, but it carries a thematic cohesion — a metallic pulse running through its songs, much like the era’s fascination with machines, progress, and cold efficiency. UFO translated that imagery into sound: tight, metallic guitar tones, rhythmic precision, and an almost mechanical groove. Yet, beneath the chrome surface lay the heart of a blues band still wrestling with emotion and human vulnerability.

The cover design by John Pasche (famed for designing The Rolling Stones’ “Tongue and Lips” logo) and illustration by David Juniper (of Led Zeppelin fame) added a visual language that tied the album to rock’s evolving aesthetic — sleek, industrial, and cinematic. Photographer Ross Halfin captured the band’s modernized image, trading the scruffy ‘70s look for something sharper, fitting the MTV generation.

Band Dynamics and Internal Friction

The sessions for Mechanix were productive but not without strain. Bassist Pete Way, whose thunderous playing had always been central to the UFO sound, was increasingly frustrated by management issues and creative disagreements. The recording process magnified these tensions, and not long after the album’s release, Way would depart the band to form Waysted. His departure marked the end of UFO’s classic era, leaving Mogg as the sole original member to carry the torch.

Reception and Controversies

Upon release, Mechanix received a mixed reception. Critics praised its craftsmanship but questioned its emotional authenticity. Some longtime fans missed the raw unpredictability of the Schenker years, while others welcomed the band’s modernized sound. The inclusion of the Eddie Cochran cover “Somethin’ Else” drew mild controversy — a rockabilly standard nestled among hard-rock anthems — but it also reflected UFO’s roots in classic rock ‘n’ roll energy.

Commercially, the album performed well enough to sustain the band’s international touring, particularly in France and Germany, where UFO retained a loyal following. However, the hard-rock world was shifting rapidly toward heavier, faster sounds — leaving bands like UFO straddling the line between heritage and adaptation.

Legacy and Artistic Value

In retrospect, Mechanix stands as one of UFO’s most transitional works — a bridge between the raw intensity of the 1970s and the polished professionalism of 1980s rock. It’s an album that captures both evolution and exhaustion, a group of veterans proving that even in an era obsessed with reinvention, they could still make the engines of hard rock roar.