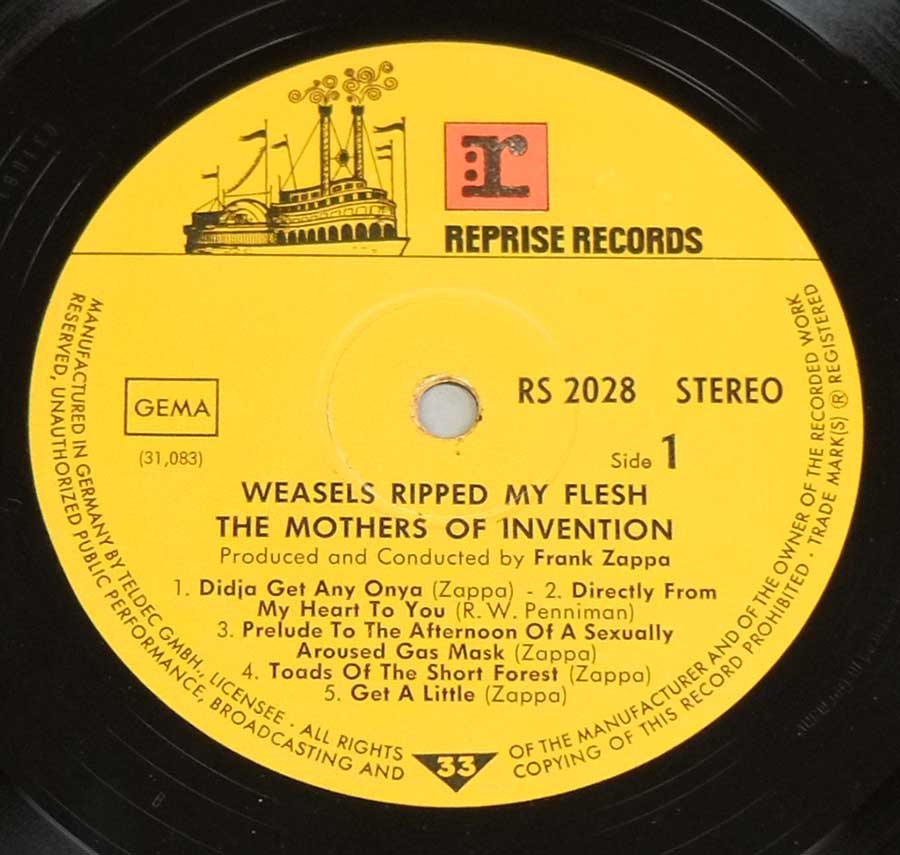

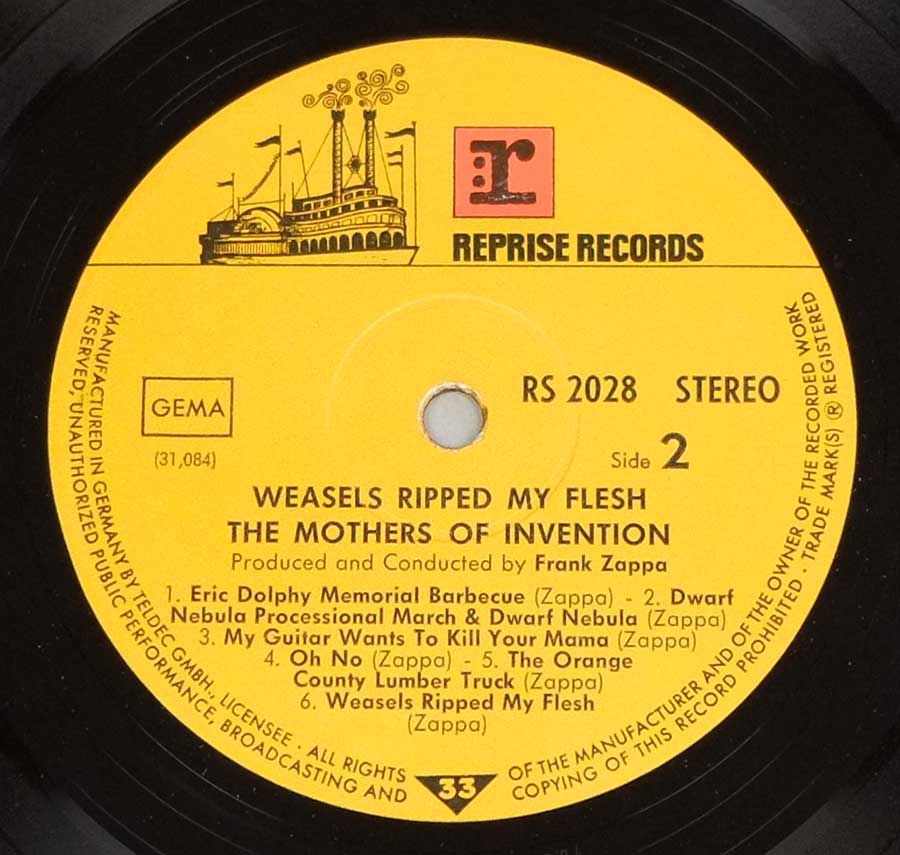

ÒWeasels Ripped My FleshÓ Ñ The Mothers explode the late-60s afterglow Album Description:

By the time this slab of controlled detonation hit, The Mothers of Invention had already scattered to the four winds and Frank Zappa was left sweeping up the confetti and shrapnel of a band that had outgrown any sane rehearsal room. Out of that post-Õ69 fallout comes a record that doesnÕt mourn the partyÕs end Ñ it samples it, splices it, and feeds it back through amplifiers until the room smells like overheated tubes and ozone.

Historical context: post-breakup, pre-amnesia

This album assembles performances and studio fragments from the fever years spanning late Õ67 through Õ69 Ñ a period when rock, jazz, and the avant-garde were courting each other with equal parts lust and sabotage. The Mothers had disbanded, but Zappa wasnÕt about to let those reels grow moss; he curated a cross-section of the bandÕs most volatile states: European halls reverberating like empty cathedrals, East-coast studios crackling with fluorescent insomnia, West-coast rooms where the floor toms sound like theyÕre plotting against you.

Musical exploration: abrasive beauty, meticulous chaos

Filed, if you must, under Jazz Fusion and Prog Rock, the music keeps wriggling out of the taxonomy. ÒDidja Get Any OnyaÓ lurches like a street parade hijacked by pranksters; ÒToads of the Short ForestÓ saws between time signatures as if meter itself were a disposable commodity. ÒDirectly from My Heart to YouÓ interrupts the demolition derby with raw, pleading soul Ñ a reminder that ZappaÕs laboratory still had a beating heart on the bench. Then the title track arrives: a smear of feedback and rupture, a final spit-take at the idea that albums should behave themselves.

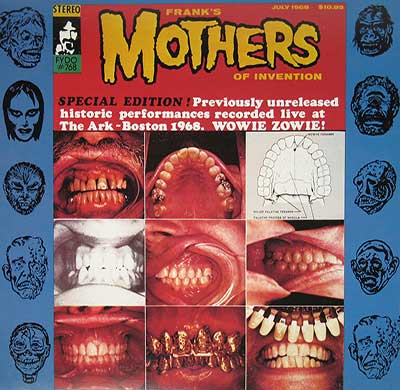

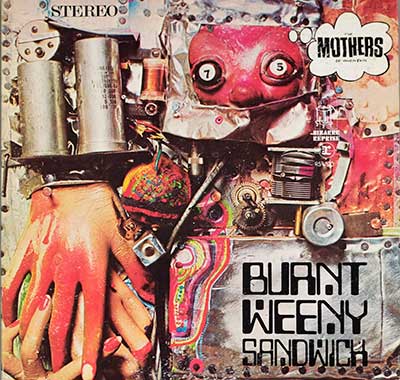

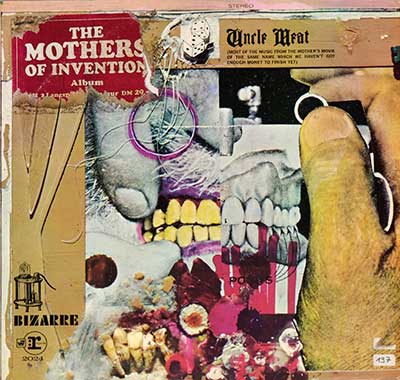

Controversies & cover art: the trap snaps shut

The notorious Òrat trapÓ sleeve Ñ a metal-mouthed infant caught mid-mischief Ñ wasnÕt approved by Zappa, which tells you plenty about the tug-of-war between art, commerce, and shock value in this era. ItÕs grotesque, yes, but also perfectly on brand for a record that treats propriety like a whoopee cushion: funny for a second, then suddenly uncomfortable, then somehow revealing.

The ensemble: a rogueÕs gallery with sharp elbows

ZappaÕs lead guitar and vocals steer the wrecking crew, but the band is a carnival of distinct tempers: Jimmy Carl BlackÕs earthbound drums, Ray CollinsÕs mercurial vocals, Roy EstradaÕs rubbery bass, Bunk and Buzz GardnerÕs brass that slices and splatters, Ian UnderwoodÕs alto lines like x-acto knives, Motorhead SherwoodÕs baritone sax and snorks (half-comedy, half-ritual), Lowell George sneaking rhythm grit, Don PrestonÕs electronics spitting sparks, Don ÒSugarcaneÓ Harris electrifying the violin, and Art Tripp tightening the rhythmic noose. ItÕs less a lineup than a kinetic argument that somehow lands on its feet.

Production & recording: Zappa the cartographer, Herb Cohen the fixer

Produced by Frank Zappa, the album isnÕt a scrapbook; itÕs a map of where the Mothers had been, drawn with pinstabs and coffee stains. Herb CohenÕs Bizarre business presence hovers in the margins, but the sonic handwriting is ZappaÕs: razor edits, punch-cut segues, and the patience to leave a dangerous silence unfilled. Sessions and captures span Apostolic Studios (New York), A&R Studios (New York), TTG (Hollywood), Whitney (Glendale), Criteria (Miami), club and hall recordings from The Factory (NY), Thee Image (Miami), the Royal Festival Hall (London), the Philadelphia Arena, and town-hall clamors in Birmingham. The result is a travelogue of rooms: you can hear the plaster in one, the stale beer in another, the polite British echo giving way to American hum.

Method to the madness: songs as field reports

ÒEric Dolphy Memorial BarbecueÓ grills harmony over an open flame, a crooked salute to a fallen titan; ÒMy Guitar Wants to Kill Your MamaÓ weaponizes a hook until it smirks; ÒOh NoÓ compresses cynicism into a bitter lozenge that dissolves too fast. Even the miniatures act like lab slides: organisms darting under a microscope, colliding, dividing, refusing to die when the light gets hot.

What it adds to the canon: not legacy, but living nerve

Forget the collector fog; what matters here is nerve. The album proves that the studio can be a scalpel and the stage a petri dish, and that rockÕs most honest moment might be the squeal right before the waveform tears. If youÕre looking for comfort, move along. If you want to hear a band collapse into new shapes while the tape keeps rolling, welcome to the snap-point where the trap springs and the music Ñ somehow Ñ laughs.