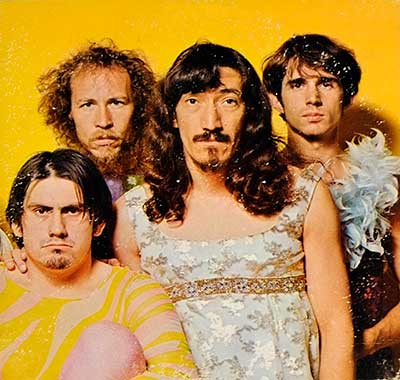

Mothers of Invention

The Mothers of Invention. Even the name sounds like a warning label. They start out in California in 1964 as an R&B outfit called The Soul Giants, and you can almost hear the harmless bar-band sweat on them—right up until Frank Zappa walks in and starts rearranging the furniture in your skull.

I picture the moment like a bad movie cut: one day you’re playing for dancers, the next you’re stuck with Zappa’s grin and his stack of ideas that don’t behave. By Mother’s Day 1965 they’re renamed The Mothers, and when the record-business grown-ups want a safer label on the jar, the band becomes The Mothers of Invention. {index=6}

From R&B to Rock Revolutionaries

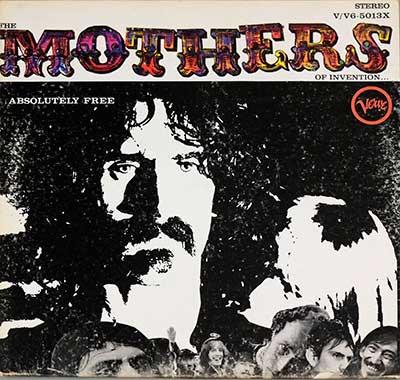

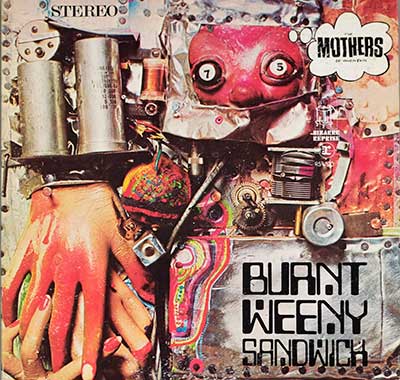

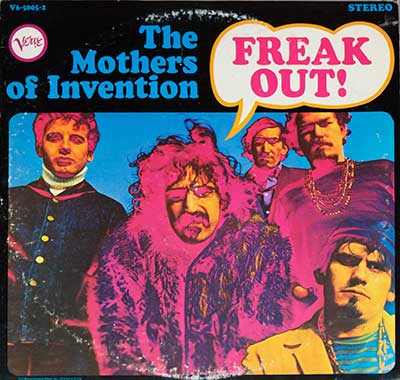

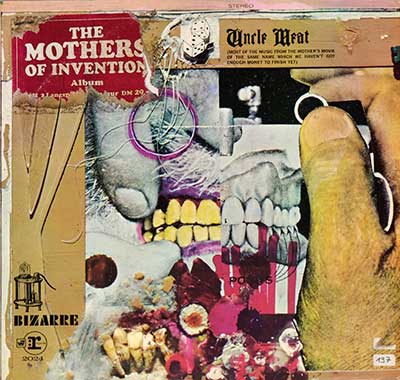

Their debut, "Freak Out!" (1966), doesn’t stroll into the room—it barges in carrying a double album and an attitude problem. The doo-wop bits smirk, the R&B roots keep peeking through, and then—bang—sound collage, odd noises, weird little left turns that feel like Zappa trying to prove (to you, to the label, to the universe) that rock can be as messy and ambitious as anything with a conservatory stamp on it.

It’s also the first time you notice the Mothers’ real trick: they can play tight when they want, but they don’t want to. They want to poke the listener with a stick and see what falls out.

Musical Innovation and Social Satire

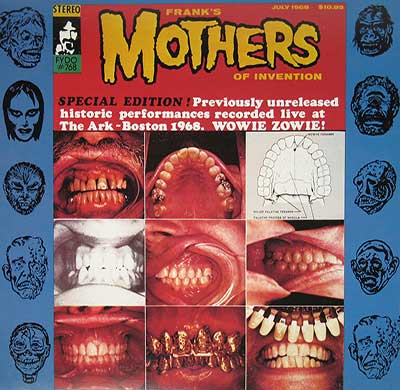

Zappa doesn’t “comment” on culture. He throws tomatoes at it. Early 1968 brings "We’re Only in It for the Money", and it’s not a warm hug to the counterculture—it’s a mirror held too close, the kind that shows your pores. Politics, hippie posturing, rock-star ego… he skewers the whole circus and somehow keeps the music catchy enough that people hum along while he’s roasting them. That’s a special talent. Slightly evil. Useful.

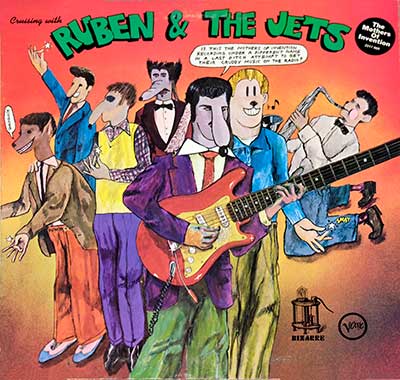

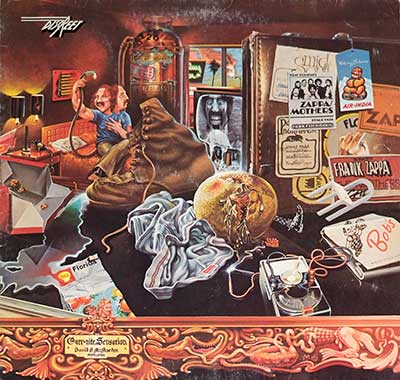

Later that same year, they swerve again with "Cruising with Ruben & the Jets" (1968), a doo-wop dream that’s equal parts love letter and prank. The joke is that it’s affectionate. The affection is that it’s a joke. Try filing that neatly.

The Zappa Spotlight

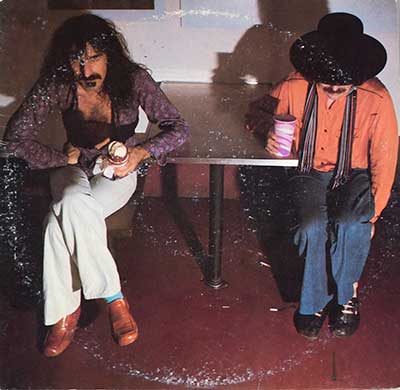

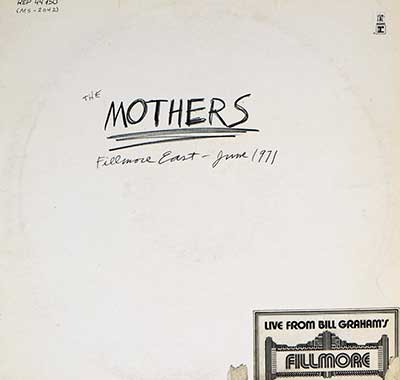

The Mothers weren’t cardboard cutouts. People like Ray Collins (vocals), Roy Estrada (bass), and Don Preston (keyboards) put fingerprints on the thing. But the gravity kept shifting toward Zappa—his charts, his rules, his pace. So the line-up churned, and by 1969 he dissolved the original Mothers. Not because the music “needed to evolve.” Because the machine was expensive, messy, and frankly impossible to keep polite.

After that, the story gets wonderfully untidy: Zappa keeps moving forward under his own name, but the old Mothers DNA keeps showing up in the playing and the personnel. "Hot Rats" (1969) is the big neon sign—Zappa solo, post-original-Mothers, jazzier and roomier, like he suddenly wanted air around the notes.

And then "Waka/Jawaka" (1972)—also a Zappa album, not “a Mothers album”—leans into that “electric orchestra” idea: horns, long lines, the sense of a band trying to sprint while carrying a grand piano. It’s not background music. It’s “pay attention or get out.”

A Lasting Legacy

If you want a clean ending, pick another band. The original Mothers stop in 1969, but “Mothers” as a credit doesn’t just evaporate, and by 1975 you even get "Bongo Fury" credited to Zappa, Captain Beefheart, and the Mothers. So no, they didn’t simply “disband in 1975.” The better truth is messier: the Mothers were a method, a moving target, a rolling argument with American music.

Their real legacy isn’t “influence.” It’s permission. Permission to be smart and dumb in the same bar. Permission to make rock uncomfortably literate. Permission to laugh at your own scene while you’re still standing in it. And if that sounds romantic, fine—just remember Zappa was also the guy who’d hand you the romance and immediately light it on fire, just to see the smoke pattern.