PATTI SMITH GROUP Band Description:

New York in the early ’70s didn’t feel like “a scene.” It felt like a drafty room with bad lighting and great intentions. Then Patti Smith and her band show up and suddenly the air changes. Not polite. Not finished. Alive.

People love to stamp her with titles later (“Godmother of Punk” and all that). Fine. But back then it’s simpler: a poet with a microphone, a band that refuses to behave, and songs that lurch between prayer and punch-up.

Early Days and the CBGB Orbit

Patti lands in New York City in 1967 and gets pulled into the downtown art grind—cheap days, long nights, and a real partnership with photographer Robert Mapplethorpe that’s equal parts survival and creation. By the early ’70s she’s reading poetry with music under it, and Lenny Kaye is already there, plugging in, turning her words into something that can bite.

CBGB (315 Bowery) becomes one of the places where it all hardens into shape—especially once the band starts doing the club in 1975. The room isn’t glamorous; the point is the pressure. Patti doesn’t “command the stage,” she prowls it, and the band follows her turns without smoothing the edges. That’s the thrill: it can wobble, it can snap, it can suddenly lock into a groove that feels like a door slamming.

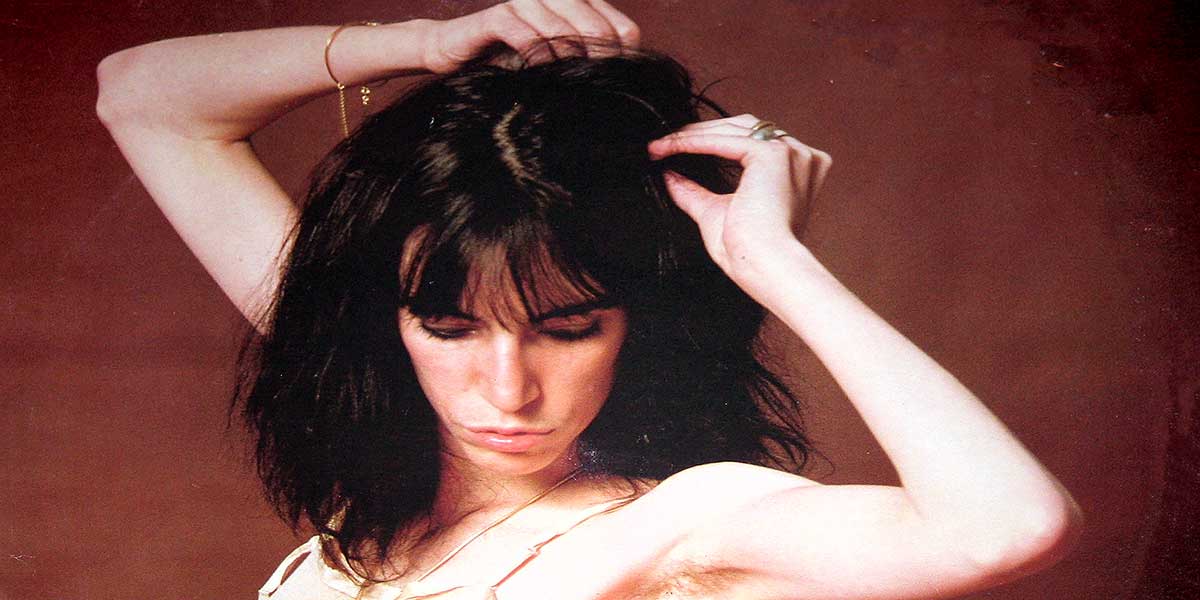

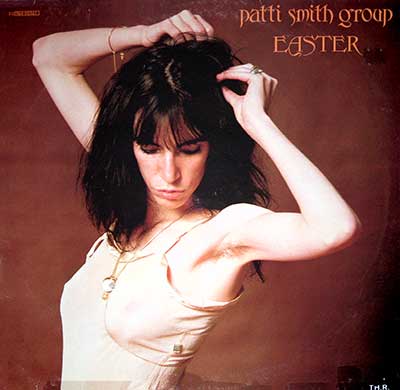

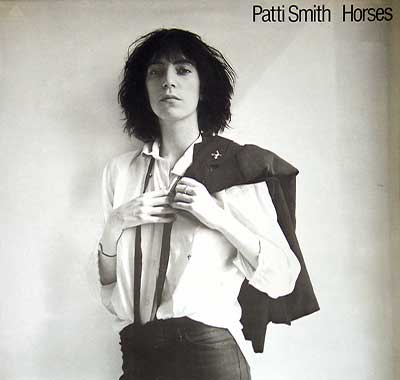

"Horses": The Debut That Didn’t Ask Permission

"Horses" drops in 1975, produced by John Cale, and it still sounds like a challenge more than a product. It opens by tearing into Them’s "Gloria" (yes, Van Morrison is part of that DNA) and Patti rewrites the mood with one of those lines you don’t forget once it’s in your bloodstream. The band plays lean, then stretches—minimalist punk bones with the nerve to improvise.

Even on the “song” songs—"Redondo Beach", "Free Money"—there’s this sense that the band is pushing the walls outward. "Birdland" goes the other way: it floats, it spirals, it dares you to stay with it. Some people call that “art.” I call it refusing to dumb it down.

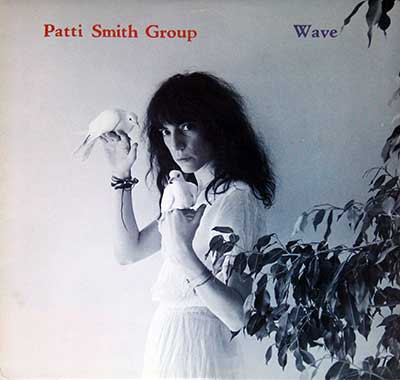

Influence and the Aftershock

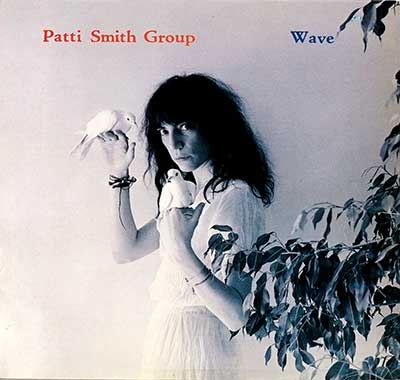

The Patti Smith Group didn’t invent punk like a patent office. They helped make it plausible in real time—poetry in the same room as rock & roll, intellect sharing a cigarette with feedback. By 1979, after the run that ends with "Wave", the band breaks up, and Patti steps away for a while. The records stay. They don’t “age gracefully.” They just keep staring back at you.

The legacy isn’t a plaque. It’s the moment you put one of these tracks on and realize you’re sitting up straighter. Not because it’s “important.” Because it still sounds like it might do something reckless.

References

- Vinyl Records: Patti Smith Group (high-resolution album cover photos)

- Encyclopaedia Britannica: Patti Smith (NYC move, early collaboration, band forming)

- CBGB (315 Bowery, club background)

- "Horses" (1975 release, producer John Cale, recording details)

- Interview Magazine: Patti Smith & Robert Mapplethorpe (NYC 1967 context)