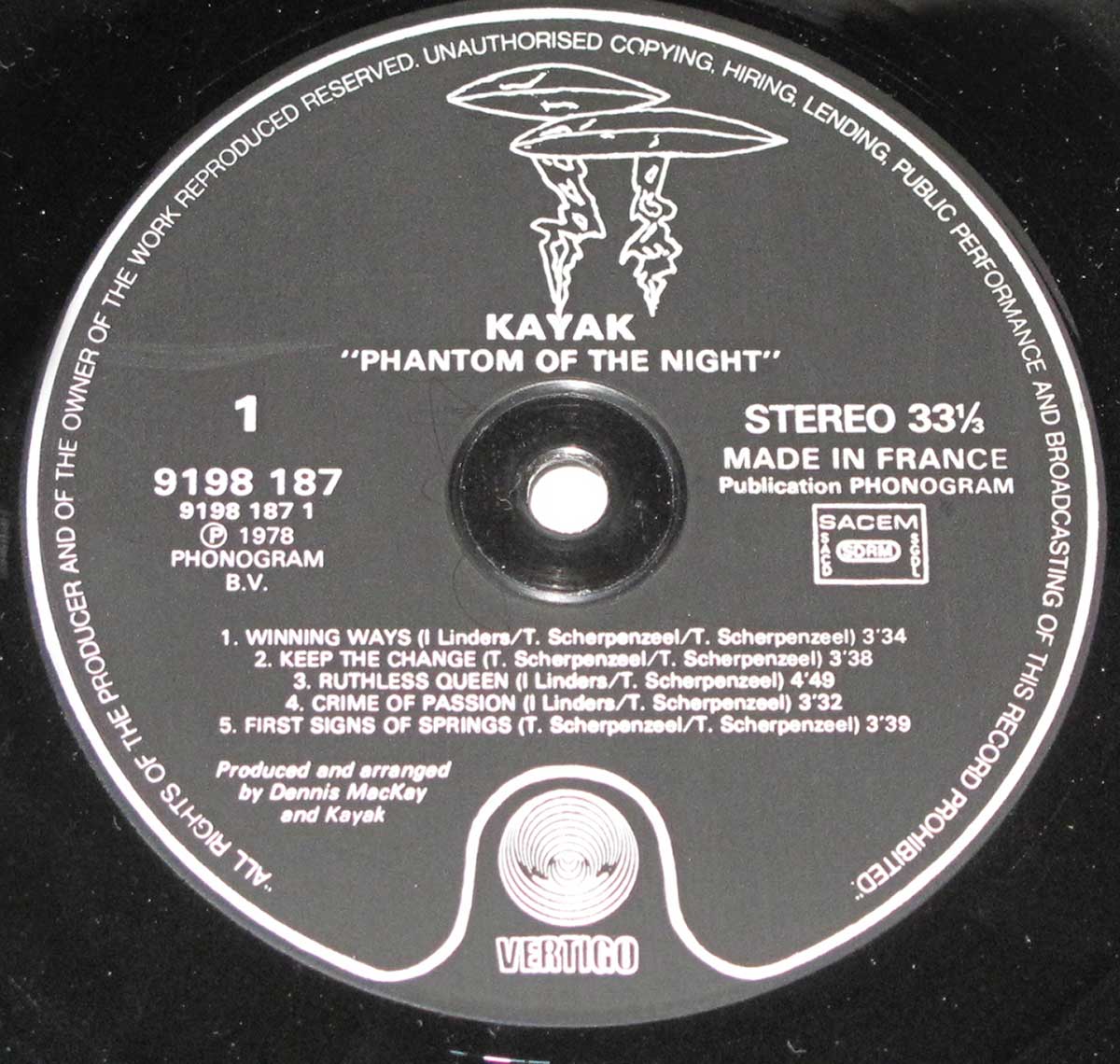

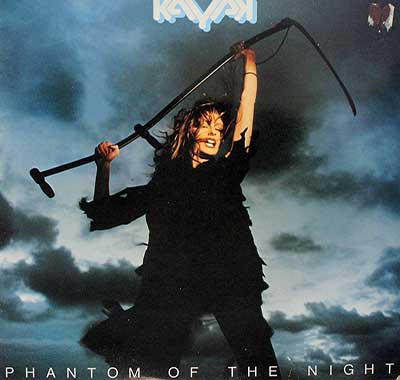

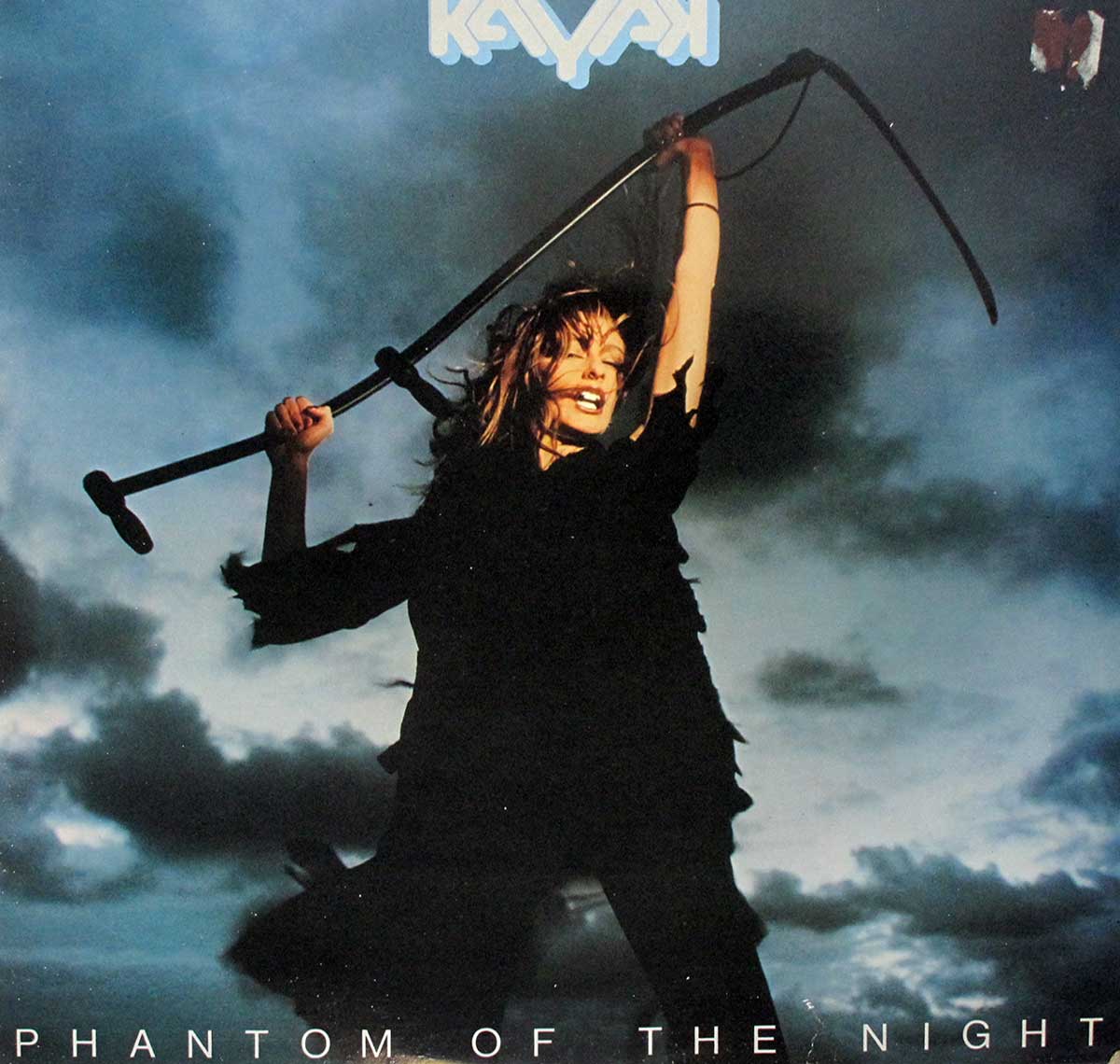

"Phantom of the Night" (1978) Album Description:

Kayak hit 1978 like a band that finally figured out how to win without surrendering, and "Phantom of the Night" is the proof: tighter songs, sharper hooks, and a pop-rock sheen that still leaves room for drama. It is their commercial high-water mark, powered by “Ruthless Queen,” a single that turned a Dutch prog institution into a chart contender. The move mattered because it captured a late-’70s reality: audiences wanted momentum, not long-winded mythology, and Kayak responded with craft, not panic. This is progressive rock learning how to dress for the street without forgetting how to dream.

1978: The Netherlands, and the End of Prog’s Free Lunch

The Netherlands in the late ’70s was modernizing fast, and the soundtrack was splintering just as quickly: punk had already landed, disco was everywhere, and new wave was creeping in with cheaper gear and sharper attitudes. Progressive rock did not die, but it stopped being the default “serious” option, especially for younger listeners who wanted impact in three to five minutes. Dutch rock had always been pragmatic, and Kayak’s pivot fits that national habit: keep the musicianship, cut the excess, and make it hit.

In the broader prog neighborhood of 1978, big names were recalibrating too: the arena era was turning technical ambition into something sleeker, sometimes colder, sometimes more radio-aware. You can hear the industry pressure in the air that year, but "Phantom of the Night" doesn’t sound bullied into compromise. It sounds like a band choosing clarity as a weapon.

The Sound: Symphonic Muscle, Pop-Rock Reflexes

The first thing that lands is the balance: keyboards stay central, but they stop behaving like a lecture and start acting like lighting. Ton Scherpenzeel’s parts are bright and architectural, setting scenes instead of building cathedrals, and that shift changes everything. Guitars and rhythm section lock in with more bite than sprawl, like the band decided that tension is more interesting than length.

The album’s texture is glossy but not sterile, dramatic but not melodramatic, and it moves with the kind of confidence you only get when the arrangements have been argued over and finally won. Choruses arrive clean, verses keep the pulse taut, and the whole record has that late-’70s “studio as instrument” polish without turning into plastic. It is prog rock with a stopwatch, and it somehow comes off as tougher because of it.

“Phantom of the Night” is what happens when a progressive band stops chasing complexity and starts chasing the listener.

Key People and the Big Line-Up Switch

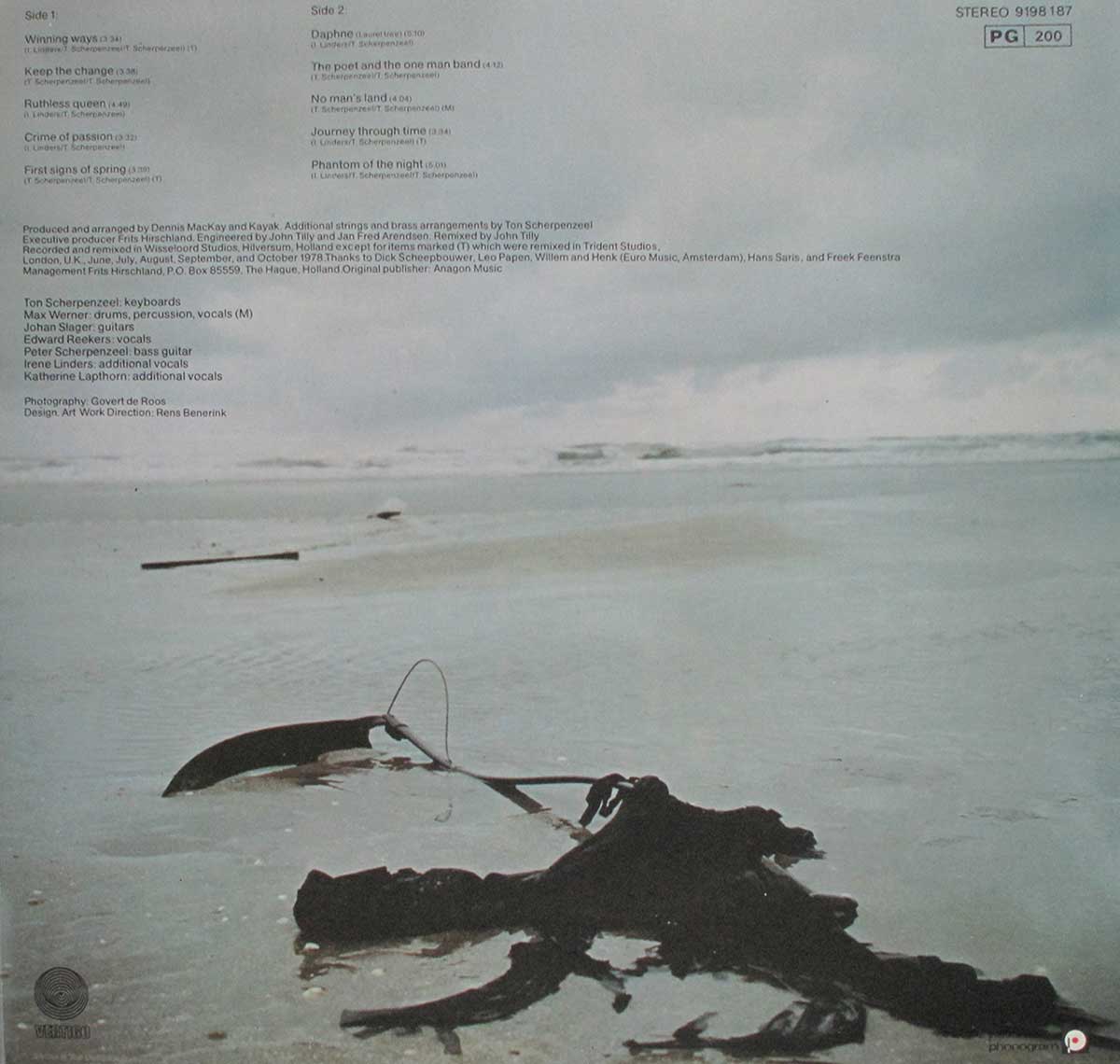

The album arrives on the back of a crucial personnel reshuffle: Max Werner, long associated with the band’s earlier vocal identity, shifts his focus to drums and percussion, and a new frontman walks in. Edward Reekers takes the lead vocal chair in 1978, and the change is not cosmetic; it’s structural. Reekers’ voice is more direct, more radio-ready, and it lets Kayak aim for hooks without sounding like they’re play-acting at pop stardom.

Bass duties also settle into a new pocket with Peter Scherpenzeel, whose playing supports the record’s tighter build and forward motion. Behind the board, producer Dennis MacKay co-pilots with the band, helping translate ambition into a clean, punchy presentation. The result is a record that sounds engineered for impact, not for showing off.

Musical Exploration: How Kayak “Went Pop” Without Going Soft

The smart trick here is that the album does not abandon progressive instincts; it reroutes them into songcraft. Instead of long detours, you get compact drama: key changes that feel like plot twists, arrangements that reveal themselves in layers, and riffs that show up exactly when they’re needed. The symphonic DNA remains, but it’s now inside the structure, not sprawled across it.

Listen for how the keyboards behave: less wandering, more framing, like cinematic scoring that keeps the story moving. The rhythm section plays with more discipline, and that discipline becomes a kind of swagger. Not the “look at me” kind, the “this band knows where the one is” kind.

Standout Tracks: Hooks, Atmosphere, and a Hit With Teeth

“Ruthless Queen” earns its reputation by being both theatrical and lethal: a chorus built to stick, a groove built to drive, and enough melodic attitude to make it feel like a statement instead of a calculation. It is the moment Kayak proves they can play the charts without losing their character. The song’s success is the headline, and the album is smart enough to support that headline rather than compete with it.

“Winning Ways” keeps the pace brisk and confident, and it shows how well the band learned the art of forward motion. The title track, “Phantom of the Night,” leans into mood: darker edges, a more cinematic sweep, and a sense of space that feels haunted without turning into parody. These songs don’t beg for attention; they take it, politely, and then they don’t give it back.

Where It Sits in the Genre: Prog Rock Crossing the Street

Call it prog, call it art rock, call it pop-rock with a symphonic brain; the label matters less than the intent. In 1978, a lot of progressive bands were either doubling down or stripping down, and Kayak chose the third way: refine. The record keeps the genre’s love of melody and structure, then trims the ornamental weight until the songs can run.

That puts "Phantom of the Night" in a very specific lane: not the sprawling fantasy of early-’70s prog, and not the punk rejection of craft, but a middle space where precision becomes the thrill. The album’s success suggests that listeners weren’t rejecting musicianship; they were rejecting bloat. Kayak delivered the lean version, and it landed.

Controversies: The “Sellout” Whisper and the Prog Purist Side-Eye

The closest thing to controversy here is the familiar late-’70s accusation: a progressive band leaning toward pop is automatically “selling out,” because apparently writing choruses is a moral crime. Some prog listeners bristled at the tighter format and shinier production, reading it as a retreat from ambition. The music itself makes the better argument: the ambition is still there, it’s just focused.

If there was friction, it was cultural more than scandalous, a push-and-pull between a changing scene and a band that didn’t want to be fossilized. Kayak’s gamble was that accessibility could be a strength, not a surrender. The charts backed them up.