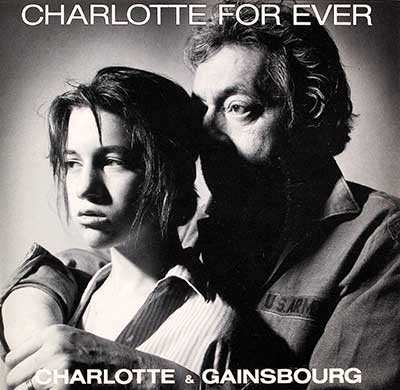

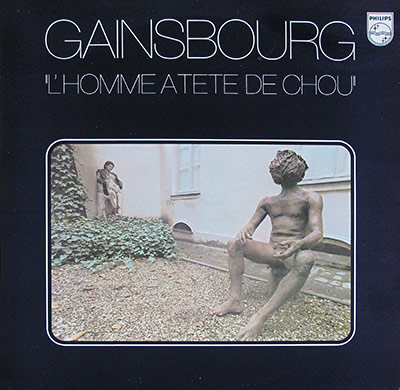

The Cabbage-Head's Descent:

The Setup

This thing opens like a rain-slick film noir you found between the sleeves of a dusty second-hand stack — smart, a little desperate, and smelling faintly of cigarette butts and old glue. Our narrator bills himself the "Man with the Cabbage Head" (yes, an inside wink to Gainsbourg's sculpture), which is a polite way of saying his brain has started to feel like overcooked brassica. He’s middle-aged, self-aware in that irritating, theatrical way, and tuned to confessional frequency: the whole album reads like a police statement written on hotel stationery or a long, messy entry from the psych ward logbook.

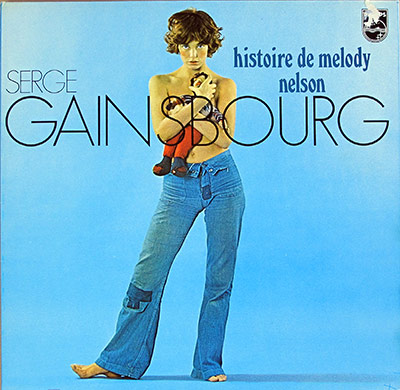

The Fatal Encounter: Marilou

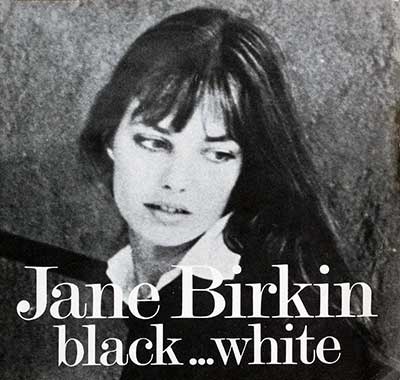

Enter Marilou — shampoo girl at "Chez Max coiffeur pour hommes" and the kind of woman who makes a man forget his address and his dignity in equal measure. He doesn’t fall in love so much as short-circuit: she becomes an incandescent idea, an erotic Platonic form, not a person. He stares; she parts hair. The record keeps spinning.

The Consuming Obsession

Tracks like "Marilou Reggae" and "Ma Lou Marilou" sound sunnier than the story they soundtrack — reggae beats and cinematic funk dressing up an increasingly ugly obsession. He pours cash and attention into an illusion. She treats desire like a fast train: get on if you like, jump off when you don’t. His jealousy becomes a tangible, stomach-turning domestique: loud, clumsy, and impossible to hide.

The centerpiece — the nearly eight-minute "Variations sur Marilou" — is less song than slow-motion surveillance. The narrator narrates her private pleasures with the exactitude of a stamp catalog entry, and none of the tenderness. It’s voyeurism served in long pours, and it makes him the sad spectator to someone else’s joy. That pain is clinical, unglamorous, and therefore much worse.

The Tragic, Violent Climax

Then the photograph: "Flash Forward" snaps him catching Marilou with other men — rockers, of course, because what else would she pick? The image shatters his built-from-cardboard reality. The pay-off is grotesquely domestic: "Meurtre à l'extincteur" — murder with a fire extinguisher — blunt, short, and stripped of melodrama. No sobbing aria, no courtroom thunder; just the action, delivered with the flatness of someone ticking off an item on a shopping list.

Lunatic Asylum

The last grooves spiral into "Marilou sous la neige" and "Lunatic Asylum." The snow might be the extinguisher foam, or the static of a mind that has been reset to white noise. The music grows repetitive and eerie, like a record stuck at the end of a side. The cabbage has gone fully vegetal: he’s lost her, lost his freedom, and lost the radio station of his reason.

Gainsbourg’s tone here is deliciously cruel — dry, precise, morally indifferent — which makes the whole thing colder and more unsettling. There’s a wink in the detail but no forgiveness in the ledger.

Fancy a deep dive into Alan Hawkshaw’s arrangements and how the music narrates this descent?