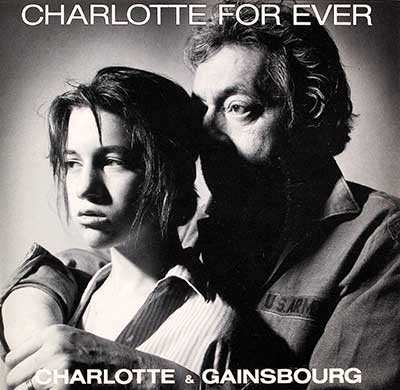

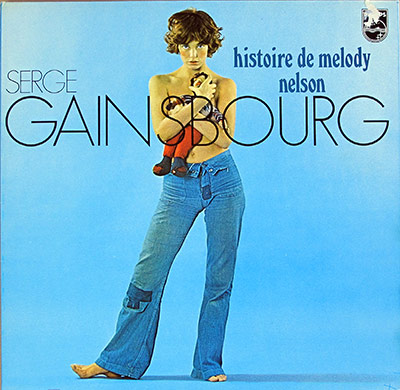

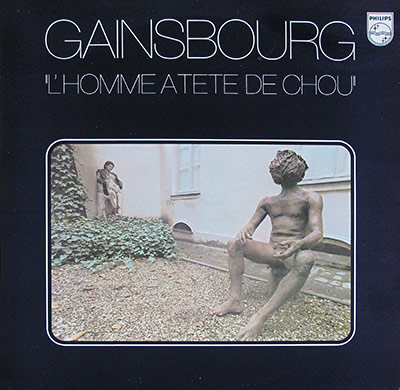

Serge Gainsbourg and the Birth of a Myth: Melody Nelson as Muse and Mirror

In 1971, Histoire de Melody Nelson dropped into a France already in the long aftershock of May Õ68, a place suspended between revolution and resignation. Serge GainsbourgÑby then a household name for his provocative wit and baroque pop chansonsÑmade a hard left turn. With this album, he authored not just a musical cycle but an entire cinematic world. The result was less a record than a novella scored with basslines and whispered confessionals. A story, a fever dream, a controversial confession delivered in a tone so deadpan it was almost tender.

The Narrative: Seduction and Symbolism

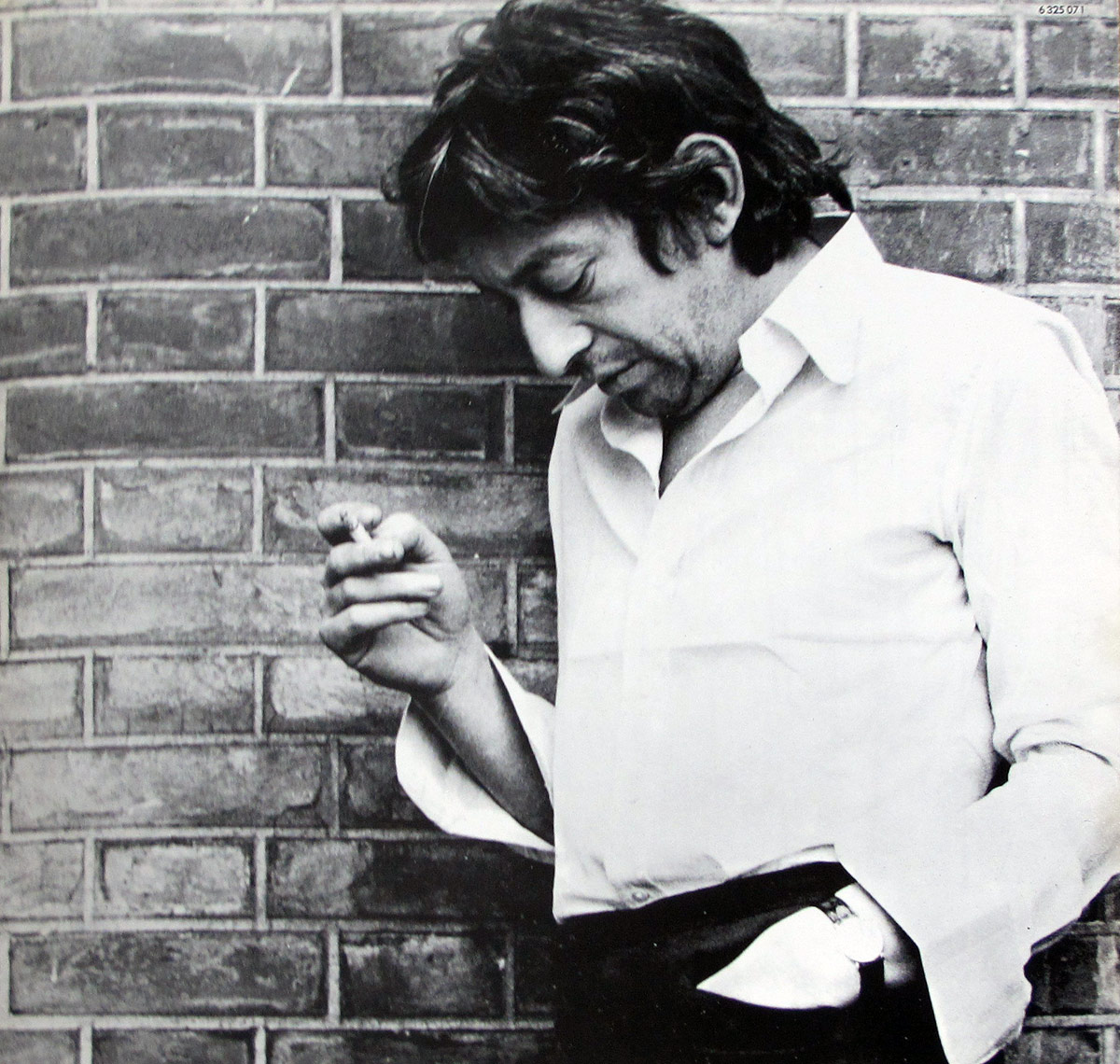

The plot is as disturbing as it is deliberate. SergeÕs narratorÑa grizzled figure of wealth and ennuiÑcrashes his Rolls Royce Silver Ghost into the bicycle of 15-year-old Melody Nelson, a freckled nymphet with flaming red hair. What follows is an ambiguous tale of seduction, guilt, and romantic despair. Gainsbourg doesn't so much sing the story as breathe it into the microphone, one unfiltered cigarette exhale at a time. In the character of Melody, he created both a symbol and a cipher: the impossible muse, the corrupted innocence, the reflection of adult desire and shame.

Musical Language: Funk, Chanson, and Cinematic Strings

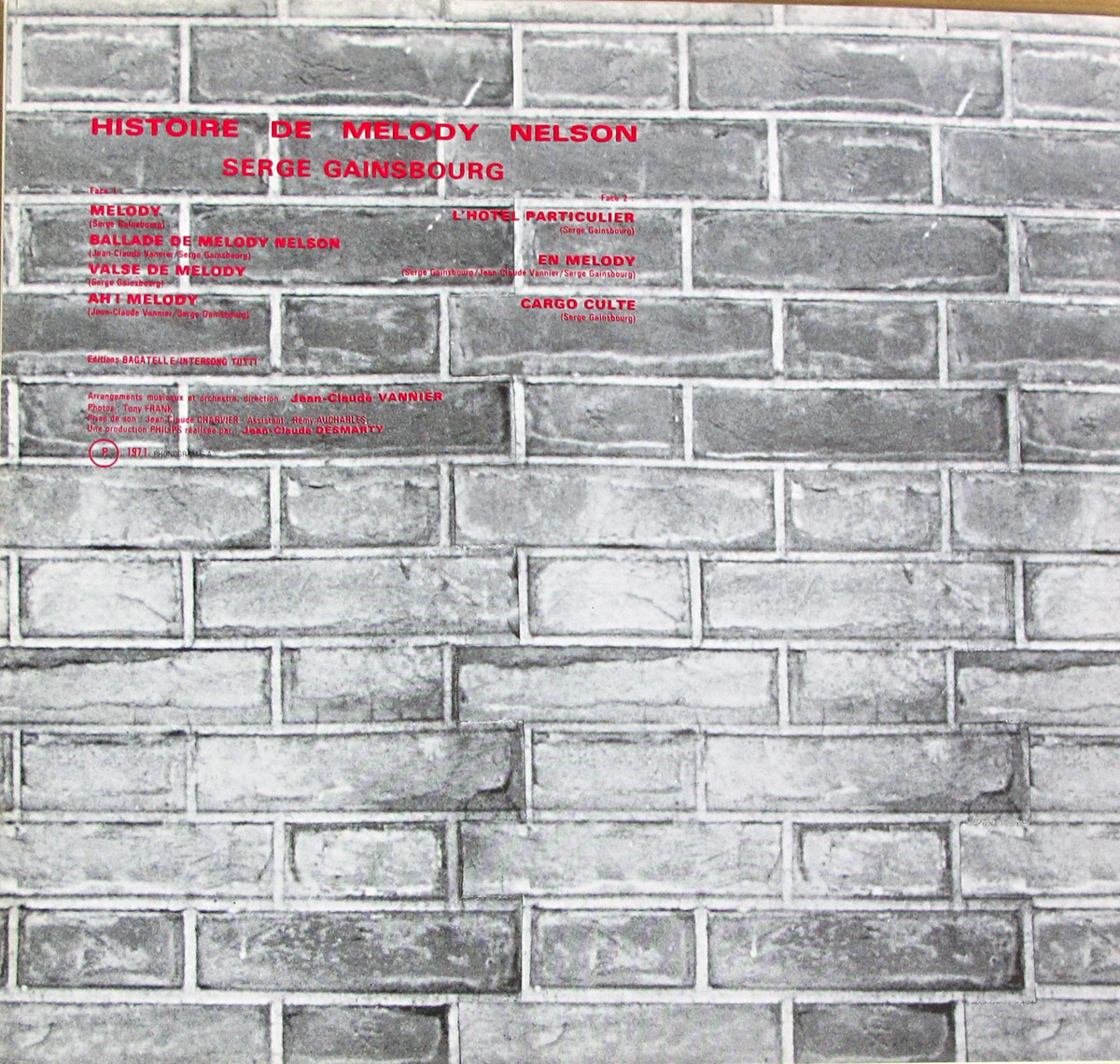

Musically, Histoire de Melody Nelson was a revelation. Drawing away from the waltz-time theatrics of earlier chansons, GainsbourgÑtogether with his brilliant arranger Jean-Claude VannierÑbuilt an aural landscape rooted in minimal funk grooves and baroque orchestration. The rhythm section, performed by British session legends Alan Parker (guitar), Dave Richmond (bass), and Dougie Wright (drums), grounded the record in a low-slung groove, the kind that could loop forever. Over this, Vannier layered lush string arrangements, harpsichords, and choral flourishes, bringing a near-symphonic melancholy to GainsbourgÕs fractured monologue.

The juxtaposition of raw rhythm and high art stringwork was no accident. It gave the album its unsettling pulse. It was chanson franaise, yesÑbut corrupted, funked-up, and thoroughly cinematic. This was not pop, nor rock, nor jazzÑit was a new French noir, an album that seemed to exist in a smoked-out red velvet room halfway between sleaze and sublimity.

Production Team and Recording

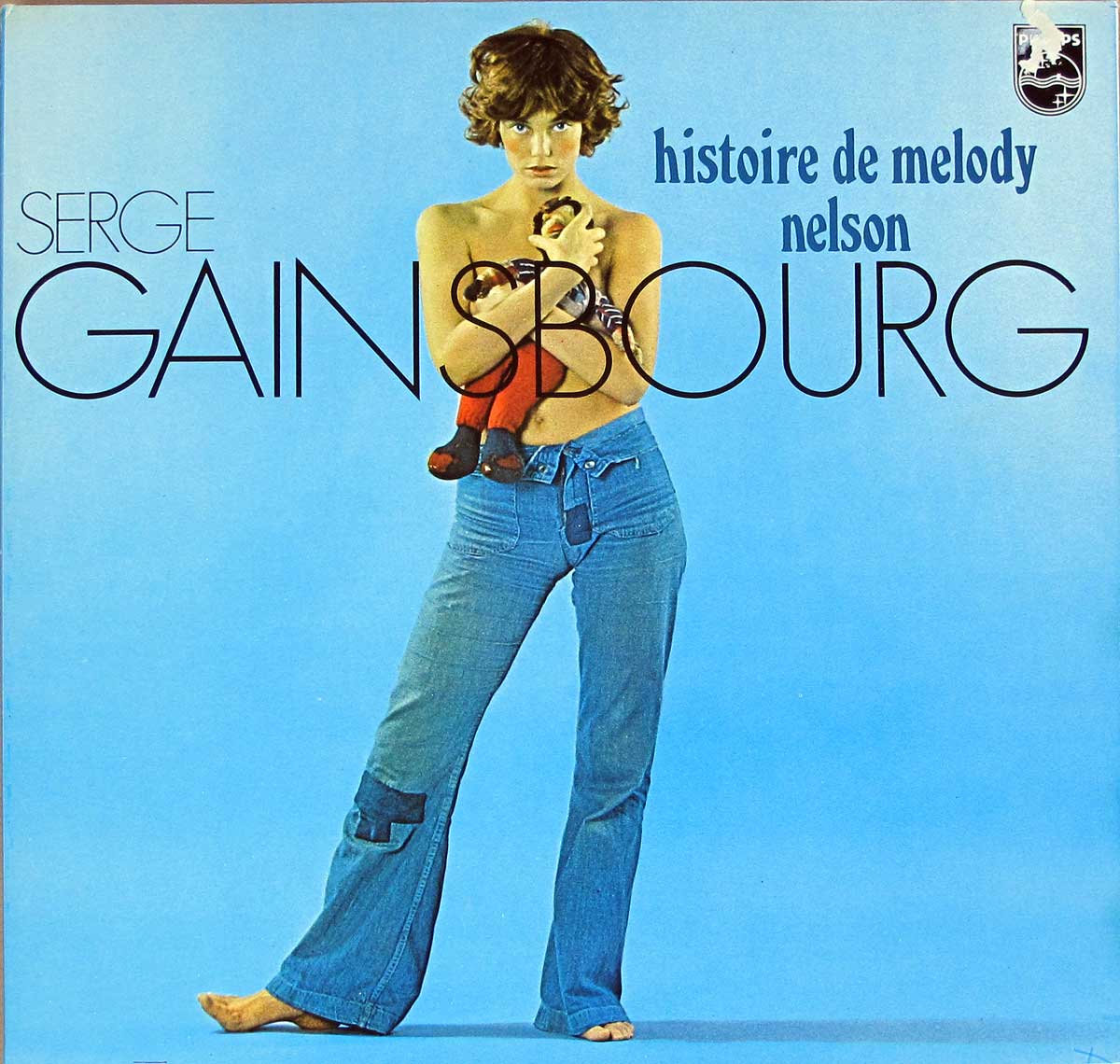

The album was produced by Jean-Claude Desmarty and recorded under the technical guidance of sound engineer Jean-Claude Charvier. Every sonic detailÑfrom the whispery vocals to the precise placement of bass and drumsÑwas deliberate. Tony FrankÕs cover photography only reinforced the cinematic vibe, offering stark, erotic portraiture that visually echoed the recordÕs narrative themes.

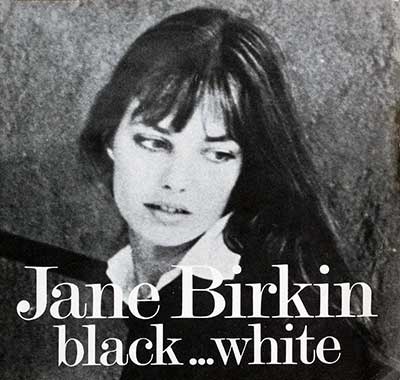

The Role of Jane Birkin

If Melody Nelson was a character, Jane Birkin was the ghost in the machine. Her occasional vocal appearances haunt the albumÕs core. Not quite duets, not quite backgroundÑher voice became a tremble, a whisper, a mirror. In reality, Birkin was SergeÕs partner at the time, and her presence on the album, though minimal, infused it with a deeply personal and voyeuristic tension. The line between art and autobiography was perilously thin.

Controversies and Cultural Shockwaves

Upon release, the album stirred immediate controversy. The narrativeÑdetailing a middle-aged manÕs obsession with an underage girlÑwas as shocking then as it remains today. But Gainsbourg was a provocateur who never sought comfort. For him, discomfort was the point. He invited listeners to confront taboo, to sit inside the grey zones of human desire, and to question their complicity.

Though some radio stations refused to play it, the album was never officially banned. Its power lay not in overt vulgarity but in suggestionÑone long insinuation wrapped in melodic melancholy. The controversy didnÕt bury the record; it defined its aura.

Different Editions and Subtle Variations

Most original releases of the album came in a striking gatefold design, housing the provocative cover shot and interior imagery by Tony Frank. There were minor variations between the French original and certain international pressings, including label design and slight mastering differences, though the core audio remained unchanged. English-speaking markets received little promotion, and no translated version was produced, leaving Melody Nelson a resolutely French artifact for decades.

A Closed Loop of Seduction and Loss

At under 28 minutes, the album resists excess. Each track bleeds into the next. From the 7-minute opener "Melody" to the tragic closing hymn "Cargo Culte", the record is a closed loopÑlike the circular motion of a vinyl groove, endlessly returning to its beginning. The story ends with MelodyÕs death in a plane crash, and the narratorÕs descent into grief and guilt. But in typical Gainsbourg fashion, he never gives away the full truth. He withholds. He mumbles. He sighs. He implicates.

Conclusion

In Histoire de Melody Nelson, Serge Gainsbourg didnÕt just tell a story. He designed a universe. With VannierÕs orchestral voodoo, British session musiciansÕ funk precision, and Jane BirkinÕs spectral presence, he created a record that remains suspended in timeÑtoo risky for radio, too rich for easy classification, and too real to dismiss. It is a work of provocation and poetry, of decay and decadence. It remains one of the most intimate hallucinations ever pressed to vinyl.