Album Description:

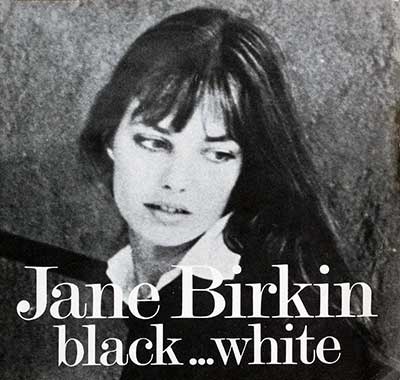

Some records don’t kick the door in. They just appear in the room, already lit, already moving. Jane Birkin’s "Lost Song" landed on 16 February 1987, and it doesn’t behave like a comeback or a statement — it behaves like a private letter that somehow slipped into the public mail.

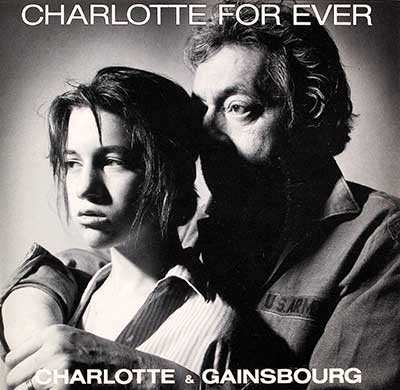

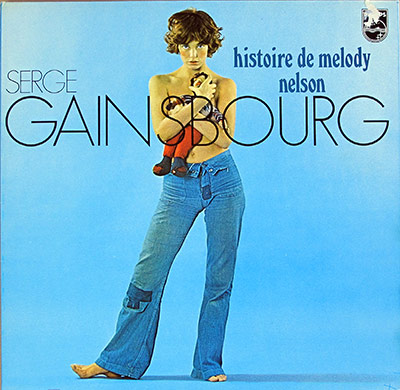

The headline fact is simple: these are songs written by Serge Gainsbourg, sung by Birkin. But the way it feels is the point — that half-whispered clarity she had, the kind that makes you lean in even when you’re sure you heard the line correctly.

The sound is dressed with taste, not perfume-clouds. Alan Hawkshaw handles the musical direction here — credited for arrangement, conducting, and keys — which explains why the album moves like a carefully guided night drive instead of a band brawl.

And no, he didn’t produce it. The production credit goes to Philippe Lerichomme. That matters, because this record’s “control” isn’t accidental — it’s the kind of control that leaves fingerprints only if you know where to look.

The recording setup is split like a good alibi: playbacks at Studio Petal Music in London, then vocals at Studio Plus Trente in Paris. You can hear that geography — London’s tidy architecture under Parisian cigarette smoke.

The musicians are exactly the kind of pros who don’t “show off”, they place things. Alan Parker on guitar keeps it precise, Mo Foster on bass adds that quietly expensive low-end, and Peter Van Hooke plays drums like he’s steering, not punching. The backing vocals (Kay Garner, Tessa Niles, Sonia Jones Morgan) don’t crowd Birkin — they hover behind her like a second thought you can’t shake.

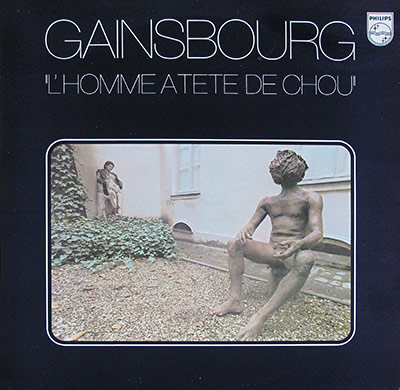

The tracklist reads like Gainsbourg being Gainsbourg: "Être ou ne pas naître" opens the album with existential bite, and pieces like "Le couteau dans le play" and "Le moi et le je" keep the mirror angled just wrong enough to be interesting.

The title track, "Lost Song", is the strange jewel: Gainsbourg folds his writing over Grieg’s “Solveig’s Song” from Peer Gynt, and Birkin sings it like she’s trying not to wake the apartment. If you came here for big 80s pop muscles, this is where you either get it… or you don’t.

A small personal anchor: this is the kind of record that makes you lower the lamp, not crank the volume. It doesn’t beg for attention — it assumes you’ll be quiet enough to notice what it’s doing. And honestly, that assumption feels slightly arrogant. I like it for that.