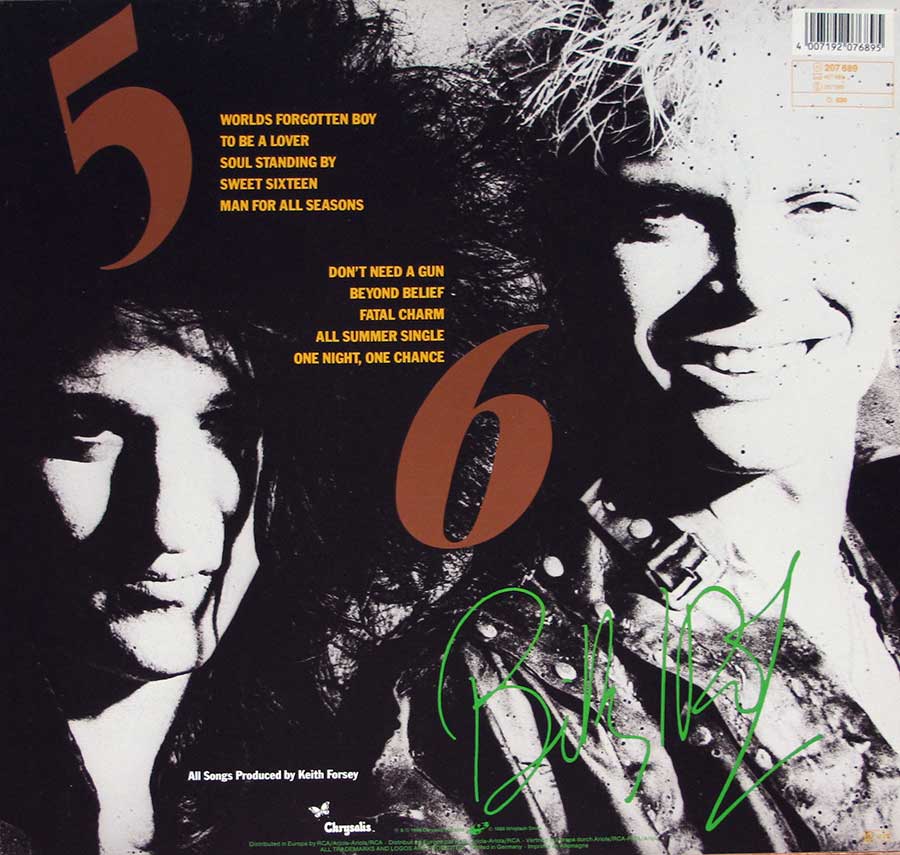

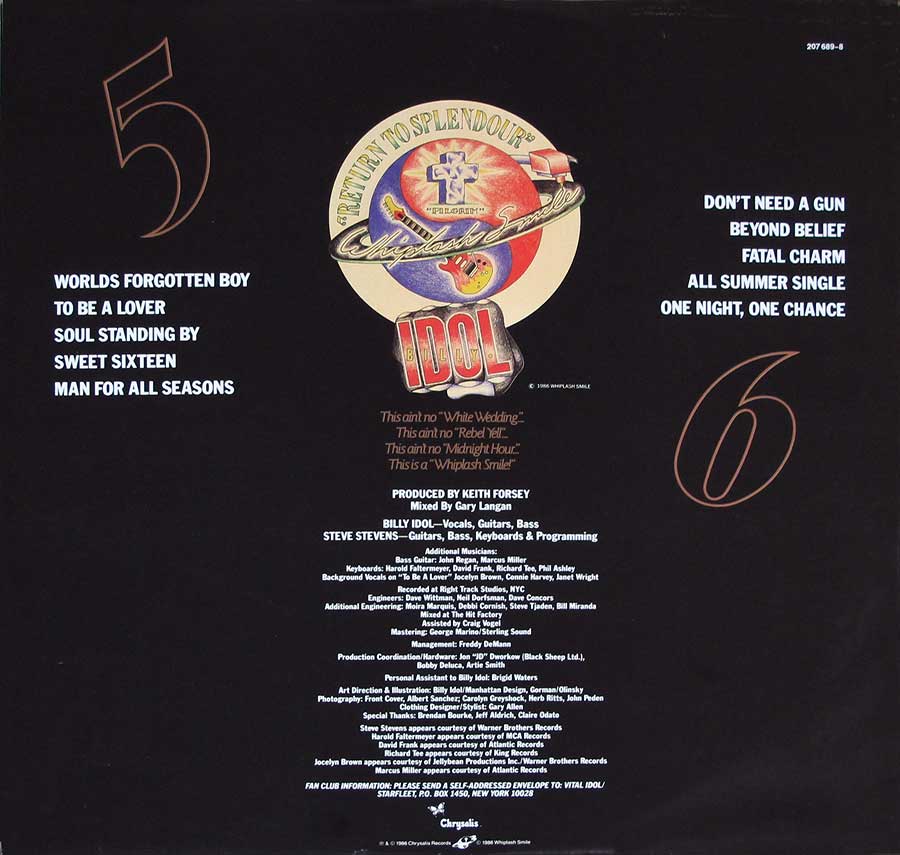

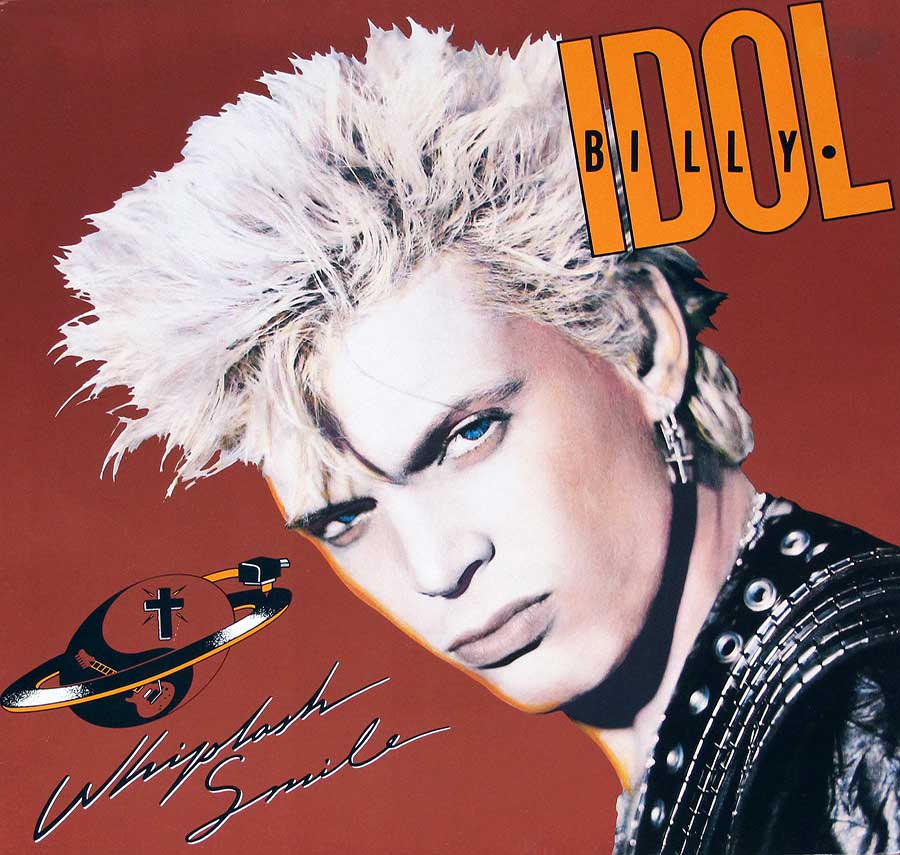

"Whiplash Smile" (1986) Album Description:

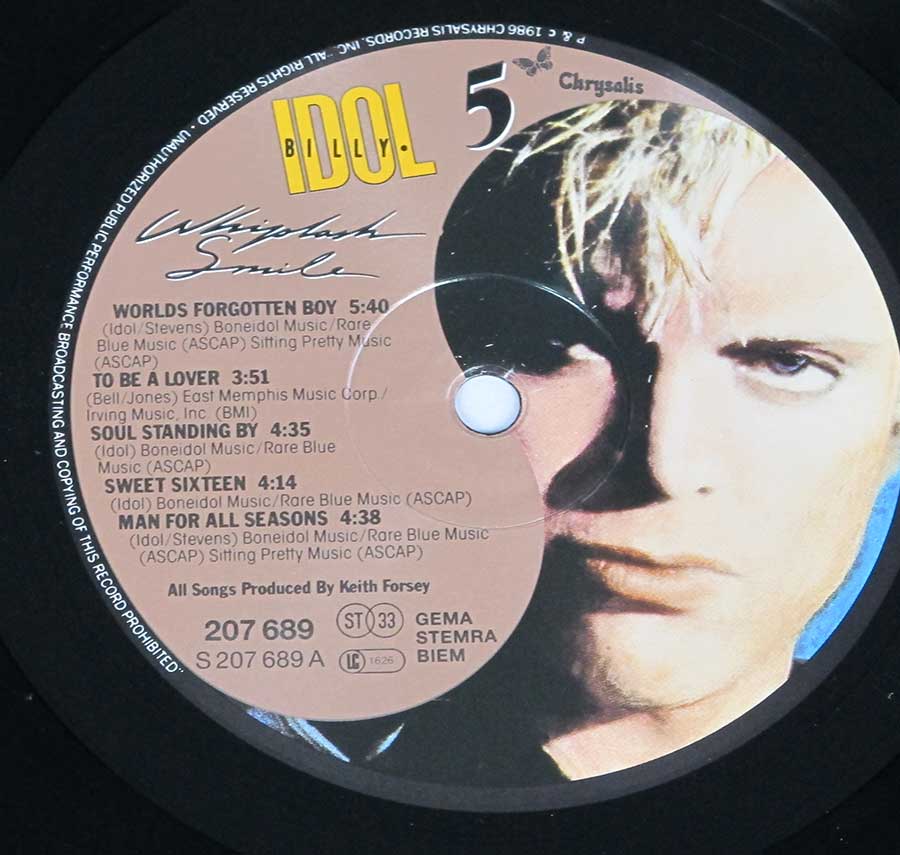

"Whiplash Smile" is Billy Idol taking his punk snarl and running it through the 1986 MTV machine until it shines like chrome. Released on Chrysalis and recorded in New York, it hit big—No. 6 on the US Billboard 200—while critics argued about whether the polish was progress or just a really expensive haircut. The result is lean, loud, and restless, with To Be a Lover doing the heavy lifting and the album’s hard-pop bite landing exactly where radio wanted it.

1986: the moment Idol had to pick a lane and refused

Mid-’80s rock was a crowded freeway: glam metal owned the arenas, synth-pop owned the clubs, and “New Wave” had become a broadcast-ready umbrella for anything with attitude and a backbeat. Idol came from the UK punk hangover, but by 1986 he was living in the American spotlight where image and velocity mattered as much as songs. That tension—street pose versus pop scale—is the real engine of this record.

Britain in the Thatcher years, America in the Reagan glare

Back home, the UK scene was splintered into post-punk, goth, and synth modernism, with bands like The Cure and Depeche Mode turning alienation into style. In the US, radio and MTV leaned hard into big choruses and bigger surfaces, while New York studios built records like skyscrapers. Idol straddled both worlds, carrying punk posture into a market that rewarded clean production and obvious hooks.

Genre map: punk rock attitude, pop rock architecture

The page calls it Punk Rock and Pop Rock, and that’s accurate—just not in the “safety pin” sense. The punk is in the clipped phrasing, the impatient tempos, the refusal to sound gentle for more than a bar or two. The pop-rock is the bright mix, the stacked chorus work, and the way a song like Sweet Sixteen can slow down without losing the glare.

What the music feels like

This is a bright, tensile record—guitars clipped and metallic, drums tight enough to bounce quarters, and synth textures that glow rather than smear. Worlds Forgotten Boy comes in with a hard edge and a fast stride, then To Be a Lover turns swagger into something danceable without apologizing. Don't Need a Gun keeps the pulse up and the message plain, which in 1986 was either admirable or annoying, depending on your mood and your station manager.

Quick scan: what changed since the early Idol playbook

- More synth sheen and programmed precision, less bar-band looseness.

- Guitar still leads, but it’s framed inside dance-ready rhythms.

- Hooks land faster; endings don’t linger for sentimental reasons.

The key people behind the glass

Keith Forsey produces and keeps the whole thing moving—no wasted space, no murky corners, everything built for impact. Guitarist Steve Stevens stays central, turning riffs into punctuation marks and solos into bright, controlled flare-ups. Engineer Gary Langan helps make it sound expensive without sounding sleepy, which is a real trick in the mid-’80s.

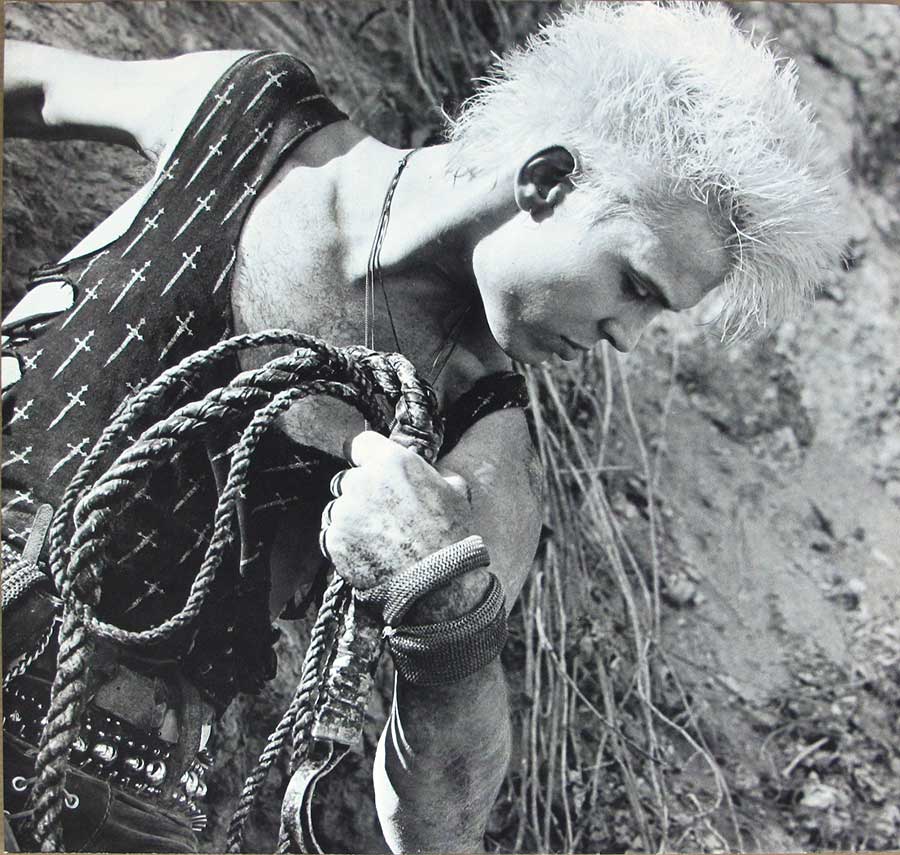

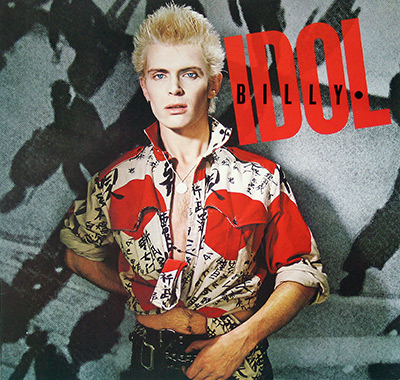

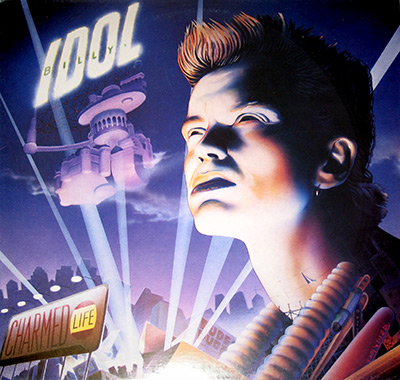

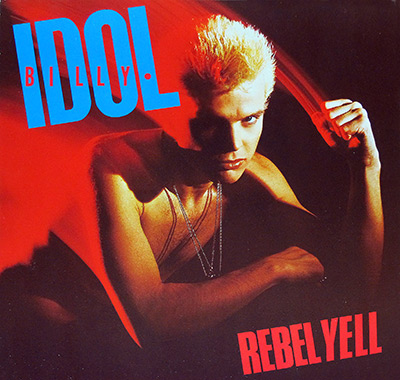

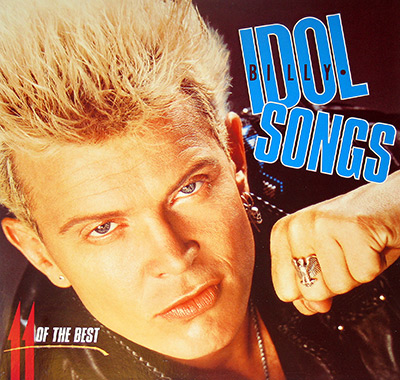

The supporting cast is a tell: Marcus Miller shows up with a musician’s instinct for groove and space, and Harold Faltermeyer brings that era’s cinematic keyboard confidence. Cover design is credited to Billy Idol alongside Manhattan Design and German/Glinsky, and the photography list—Albert Sanchez, Carolyn Hreyshock, Herb Ritts, John Peden—signals that image wasn’t decoration; it was part of the record’s equipment.

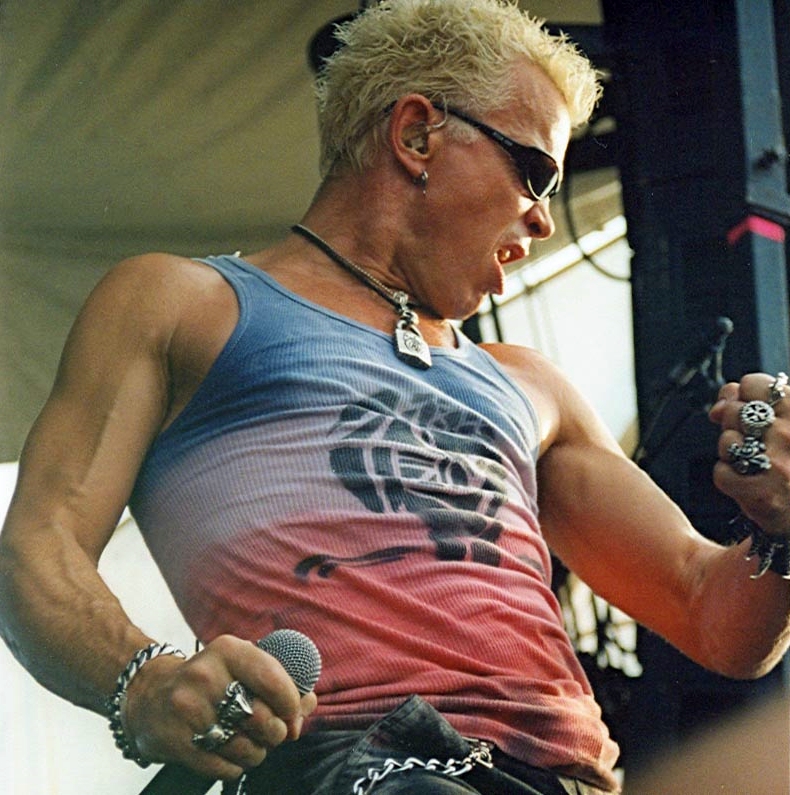

Idol’s timeline into this record

Billy Idol doesn’t form a “band” here in the classic sense so much as he builds a working unit around a core identity. The story runs from Generation X in late-’70s London to a solo breakout in the early ’80s, then straight into this mid-decade pressure point where success demanded a bigger, tighter presentation. "Whiplash Smile" is the sound of that presentation being assembled at full speed.

Timeline (fast, useful, no fluff)

- Late 1970s: Idol rises with Generation X in the UK punk fallout.

- Early 1980s: solo career goes big in the US, MTV-era visibility follows.

- 1985–1986: recording in New York; production pushes toward sleek hybrid rock.

- 1986: "Whiplash Smile" arrives with singles built for radio and video.

Reaction and the one real controversy: authenticity arguments

The album’s success didn’t settle anything; it started an argument. Fans who wanted the punk-era grime complained about the gloss, while mainstream listeners heard a rock star sharpening his tools for the decade he was living in. The closest thing to a true “controversy” is that old fight—street credibility versus pop reach—and Idol leaned into the reach with a grin that practically dared you to complain.

This is punk attitude taught to speak fluent 1986: loud, bright, and built to move.