"Melissa" (1984) Album Description:

1) Introduction on the band and the album

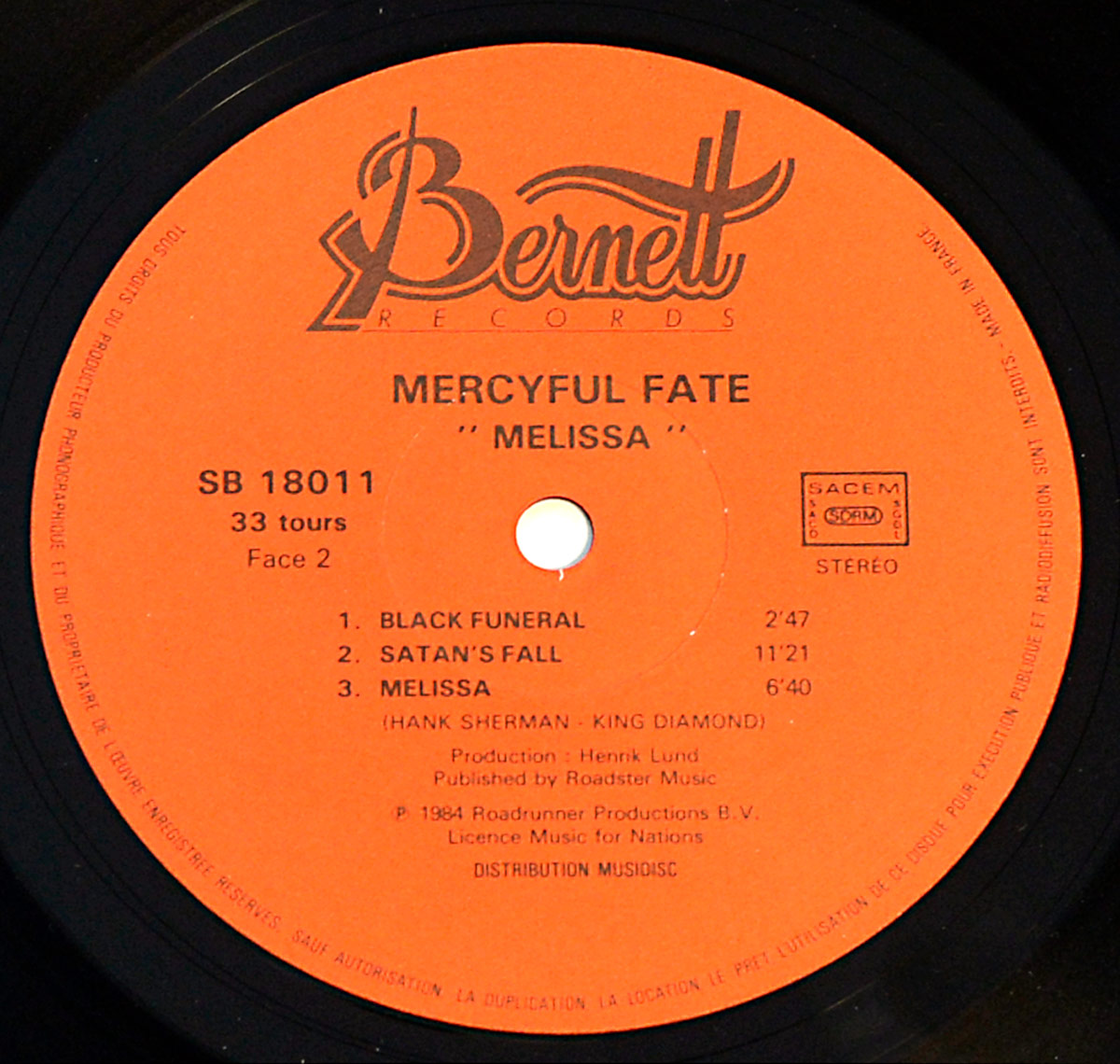

There’s a moment in metal history where the grin changes. Less “arena poster,” more “don’t make eye contact.” For me, that moment is Mercyful Fate’s "Melissa" — and yes, this is a 1984 French Bernett pressing, the kind of copy that still feels like it should come with a warning label and a suspicious look from your parents.

It doesn’t sound “new band, nice effort.” It sounds like a band arriving with intent. King Diamond isn’t just singing, he’s acting like the microphone owes him money. And Hank Shermann and Michael Denner don’t “harmonize” so much as circle each other like two switchblades deciding who gets the first cut.

2) Historical and cultural context

The album was recorded and mixed in Copenhagen in July 1983, and then this copy shows up as 1984 France — which feels exactly right for that early-’80s European shake-up, when metal was shedding its polite manners and picking up stranger habits.

People call it “the underground” now like it’s a genre tag. Back then it felt like an actual place. Low ceilings. Sweaty rooms. Tape-traded whispers about bands that sounded like they meant it. Not “edgy,” not “spooky,” but committed in that slightly alarming way.

And while plenty of heavy bands were getting bigger, Mercyful Fate leaned into weirder. Not as a gimmick. As a choice. Which is honestly the only kind of weird that ages well.

3) How the band came to record this album

"Melissa" was cut at Easy Sound Recording in Copenhagen, with Henrik Lund producing and Jacob J. Jorgenson engineering. Those credits matter because the whole record lives or dies on whether it feels present — like you’re right there, close enough to hear the room breathe and the amps glare back at you.

The playing has that “rehearsed hard” backbone, but it never turns safe. You can hear ambition in the twists and long corridors, sure — but you can also hear hunger. The kind that keeps the songs from getting comfortable.

The best part is the attitude under it all: everyone sounds like they showed up knowing this would either get them banned from living rooms… or become the reason certain teenagers stopped caring what living rooms thought.

4) The sound, songs, and musical direction

Sonically it sits in that sweet-ugly spot between blackened atmosphere and thrash-adjacent urgency. The riffs gallop, then hook left. The drums shove everything forward like they’re late and annoyed about it. The melodies flirt with tradition right up until they turn around and bite.

"Evil" doesn’t “open” the album. It kicks the door in and decides your furniture placement is wrong.

"Curse of the Pharaohs" struts around like it owns torchlight and ancient dust. It’s cinematic, but not in a soft way. More like: yes, this is the scene, and no, you don’t get to change the channel.

"Into the Coven" is the catchiest bad idea on the record — an invitation wrapped in threat, with candle smoke in its hair.

"Satan's Fall" is the long ritual. It sprawls. It shifts. It escalates. Like a serial story that keeps getting wilder until you realize the band is daring you to stay in the room. I do. Every time.

And "Melissa" (the title track) doesn’t just land the ending — it stamps the album with that feeling Mercyful Fate does best: this isn’t being played, it’s being summoned.

5) Comparison to other albums in the same genre/year

1984 is one of those years where metal starts splitting into sharper shapes. Faster here, colder there, meaner everywhere. Everyone was committing harder — some with precision, some with rawness, some with pure malice.

If you want three 1984 landmarks for the general weather (not the whole forecast), these do the job:

- Metallica – "Ride the Lightning" (1984): tight, hungry, and sharp enough to slice clean.

- Slayer – "Haunting the Chapel" (1984): short sermon, delivered with a blade under the robe.

- Bathory – "Bathory" (1984): rough, cold, and absolutely not interested in polishing the edges.

Mercyful Fate doesn’t win by being the fastest or the filthiest. Their advantage is the theater. Everything feels staged, lit, costumed — not to impress you, but to dare you to laugh. And the joke is: they’re dead serious.

6) Controversies or public reactions

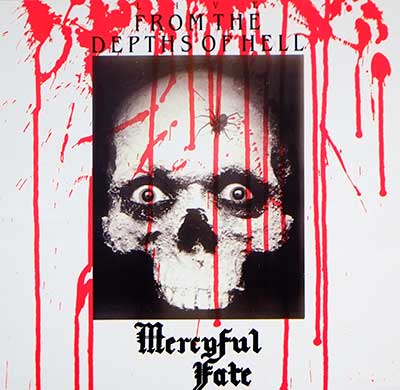

Controversy came pre-installed: occult themes, a vocalist who didn’t treat satanic imagery like a Halloween joke, and a culture primed to panic. So yeah, some people reacted like the record was going to crawl out of the sleeve and eat the family dog.

A couple years later, "Into the Coven" got pulled into that familiar outrage machinery — the kind that treats music like evidence and teenagers like suspects.

Which, of course, only made it feel stronger to the kids who needed it. Nothing sells “forbidden” like adults yelling “FORBIDDEN” into a megaphone.

7) Band dynamics and creative tensions

The fun danger here is the push-pull: King Diamond brings the narrative and character work right up front, while the guitars keep the whole thing muscular enough that it never dissolves into pure stage smoke.

That friction is the engine. Songs like this don’t feel “performed,” they feel negotiated — like everyone’s arguing in real time, then suddenly locking into the chorus with a shared grin.

Even when arrangements stretch out, you never get the sense they’re drifting. Somebody in that room wanted this to matter, and the rest refused to let it go soft. Bless them for that.

8) Critical reception and legacy

"Melissa" didn’t need trophies to spread. It needed believers: tape traders, collectors, guitar obsessives, the people who heard it once and immediately started looking around like, “Wait. We’re allowed to do this?”

Over time it stopped being a curiosity and started acting like a reference point — not because it “influenced” everything in a neat family-tree way, but because it proved you could be theatrical, sinister, and musically sharp all at once without apologizing.

And it still hits for one boring-but-true reason: it sounds committed. Like a real room in Copenhagen where the lights stayed low and nobody, absolutely nobody, was thinking about radio.

9) Reflective closing paragraph

Sliding this French Bernett copy out of its sleeve still gives me that collector jolt — that tiny spike of “I shouldn’t own this,” which is hilarious now, but the feeling is real.

Decades later, the riffs still smell faintly of beer, sweat, candle wax, and misplaced optimism. And if that doesn’t belong in a record collection, then neither does rock ’n’ roll. Deal with it.