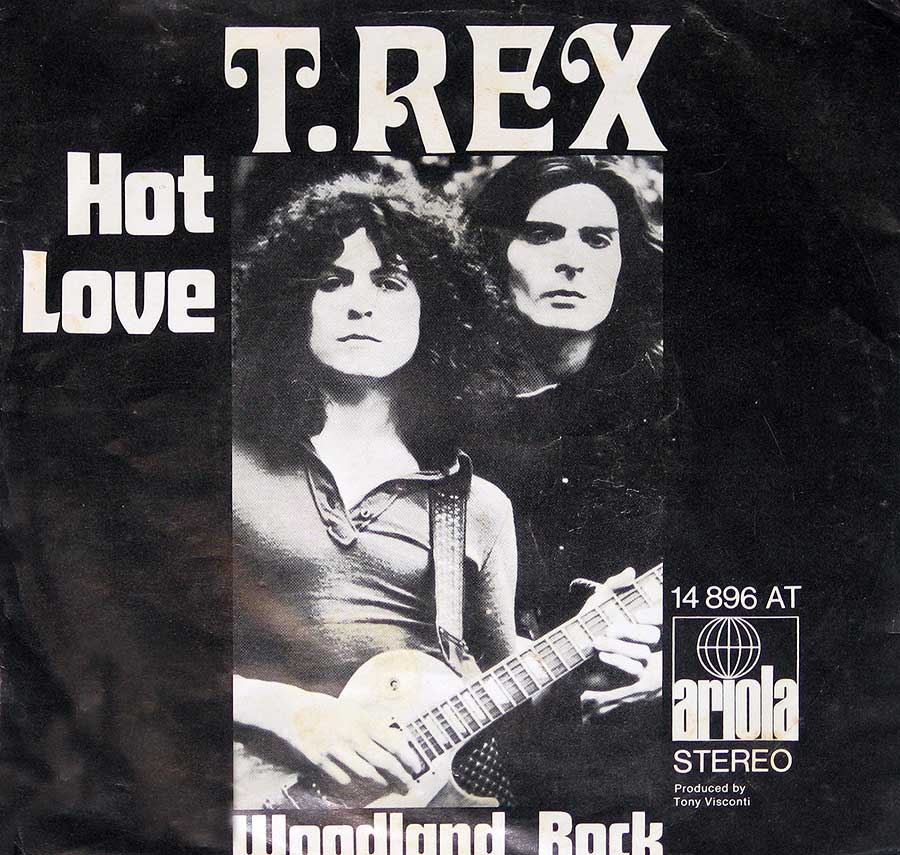

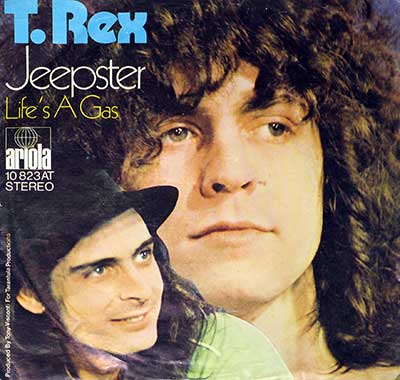

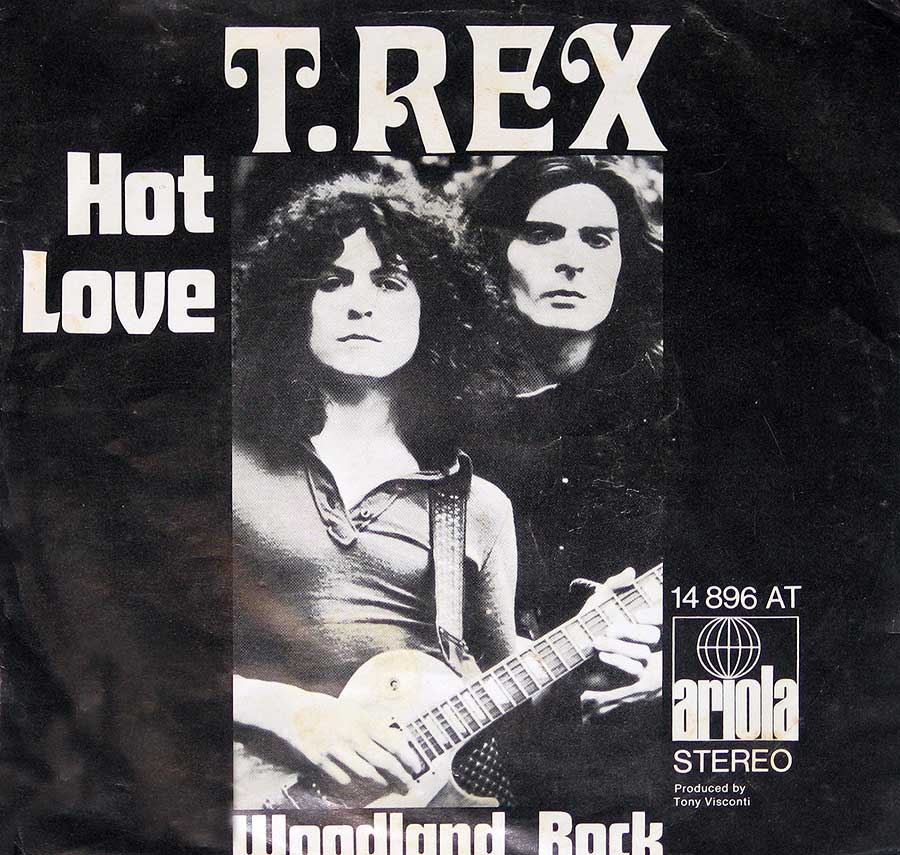

"Hot Love" b/w "Woodland Rock" (1971) Album Description:

T. Rex hit the UK in early 1971 with “Hot Love” and didn’t so much climb the charts as move in and change the furniture. It went to No. 1 and stayed there for weeks, and the song’s big-sparkle groove made rock feel dangerous again without having to play louder than a jet engine. The A-side is pure glam ignition: a stomp you can wear, a hook that grins back, and Marc Bolan singing like he’s already halfway down the runway. Flip it over and “Woodland Rock” shows the same band with the lights turned lower and the teeth a little sharper.

Britain, 1971: the hangover and the glitter

Britain in ’71 was living between busted post-’60s dreams and the first hard edges of the decade: strikes, headlines, and a lot of kids who didn’t feel like waiting politely for the future to arrive. Rock had split into tribes—heavy, progressive, rootsy—and plenty of it took itself so seriously you could hear the frown lines through the speakers. “Hot Love” shows up like a bright match: it doesn’t argue, it moves.

Glam rock before it had a rulebook

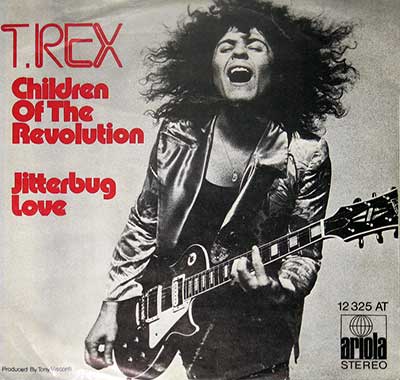

Glam rock wasn’t a museum label yet; it was a reaction, a new pop muscle with old rock ’n’ roll bones and fresh paint. You can line it up beside David Bowie circling his own reinvention in 1971, and the early momentum building toward bands like Slade and The Sweet as they sharpened their pop-metal punch. T. Rex didn’t invent flash, but Bolan gave it a beat you could march to.

- Glam’s basic move: simple chords, big hooks, and a rhythm section that walks like it owns the street.

- Glam’s attitude: theatrical, sexy, sly—less “guitar hero” and more “pop star with a switchblade grin.”

- Glam’s collision: ’50s rock ’n’ roll swagger rerouted through modern amps and a youth culture ready for costumes.

The sound: satin stomp with bite underneath

“Hot Love” runs on a thick, rolling pulse—part boogie, part chant—where the guitars glitter instead of growl. Bolan’s vocal rides the groove like he’s leaning into the mic to tell you a secret, then laughing when you believe him. The track is all texture: handclap snap, elastic rhythm, and a chorus that lands like a spotlight.

“Woodland Rock” feels like the after-hours room behind the main stage, darker and a little rougher at the edges. It keeps the momentum but trades some shimmer for grit, like the band is reminding you they didn’t come out of a fashion magazine. Together, the two sides make a neat little statement: glam can smile and still hit.

Key people: the song, the studio, the spark

Marc Bolan wrote it and performed it like a man who understood that pop isn’t the enemy of danger—it’s the delivery system. Producer Tony Visconti keeps the track clean but not polite, balancing that stomp so it hits radio like a fist wrapped in velvet. Recorded at Trident in London, the sound comes out tight, bright, and confident, like they knew exactly what they were building.

“Hot Love” is the moment where rock stops brooding in the corner and starts flirting with the room.

Band story in fast cuts: from woodland folk to electric heat

T. Rex began as Tyrannosaurus Rex in 1967, a Bolan-led, psychedelic-folk creature that felt like a campfire dream with better vocabulary. As the years turned, the sound electrified and the name shortened, like they were shaving off the old skin to move faster. By the early ’70s, the group had grown into a tougher unit around Bolan, built for singles and stages instead of incense and acoustic spells.

The early lineup changes weren’t drama for drama’s sake; they were the mechanics of transformation. Bolan kept the creative wheel, and the band around him evolved as the music demanded more punch and less mist. By the time “Hot Love” hit, T. Rex sounded like a band that had finally found its street clothes.

Controversy: not riots, but raised eyebrows and a new kind of swagger

The “Hot Love” storm wasn’t about police reports; it was about posture, presentation, and how pop television suddenly looked different. When Bolan brought satin and glitter to prime-time performance, it rattled a certain kind of gatekeeper who liked rock to stay rugged and male-coded. The controversy was the quiet kind: snarky commentary, muttered discomfort, and then the obvious reality—kids loved it, and the culture shifted anyway.

In a genre that had been splitting into seriousness and heaviness, glam’s refusal to be solemn was the provocation. “Hot Love” didn’t ask permission to be pretty, loud, and catchy at the same time. That was the shock: the audacity of joy, dressed up like trouble.