The Secret History Behind the “Porky Prime Cut” Etchings

I learned the “Porky” thing the same way most people do: by accident. A record on the platter, a desk lamp aimed at the runout, and that little moment where the dead wax flashes back at you like it’s trying to confess something.

The name behind it is George “Porky” Peckham — born in Blackburn, raised around Liverpool, and already deep in the business by the time he landed in the cutting room at Apple Studios in late 1968. Not a frontman. Not a myth. A cutter with sharp ears and a refusal to behave.

When he was happy with a lacquer, he didn’t just let it leave the room quietly. He scratched his grin into it. “A Porky Prime Cut”, sometimes just “Porky”, and other times the sideways little alter-egos like “Pecko” or “Pecko Duck”. It wasn’t stamped. It was etched — handwriting, attitude, and a tiny act of vandalism that somehow became tradition.

Collectors love to treat that phrase like a guaranteed upgrade. I get it. I’ve done it too — seen the mark and felt my expectations rise before the needle even drops. Sometimes the hype pays off: the cut feels bolder, more alive, like someone leaned forward and said, no, we’re not playing polite today. But it’s not magic. It’s a person making choices, and people are inconsistent creatures on a good day.

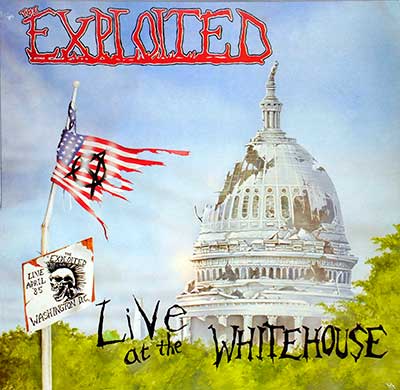

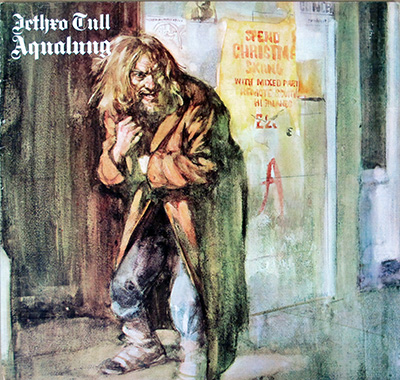

The fun part is how wide his fingerprints spread. You’ll find him hiding in plain sight on all kinds of UK pressings — punk and post-punk especially. Joy Division turns up with Porky inscriptions on releases like “Transmission”. Buzzcocks too. And then you get the famous geek-bait like Led Zeppelin IV, where “Porky” and “Pecko Duck” have sent more than a few of us down the rabbit hole with a loupe and a smug grin.

Peckham also had the kind of brain that enjoyed tricks: the Monty Python album with the “three-sided” gag (two concentric grooves on one side) is the sort of idea that sounds like a prank until you remember the cutter has to actually make it work. Which he did. Of course he did.

What I like most is that it doesn’t feel like branding. It feels like presence. A human leaving a little scrawl where the industry usually hides the hands that shaped the sound. And yeah — every time I catch that mark in the light, I still get that stupid little jolt of connection. Not reverence. More like a wink that says: relax, I was here, and I wasn’t boring.

References

- George Peckham (overview, Apple Studios start, inscriptions)

- Discogs: “Porky” (George Peckham) artist profile

- Muzines: “Cut It Out” (One Two Testing, 1984) — Peckham in the cutting room

- Sound & Vision: “Porky’s Prime Cuts” (background + inscriptions)

- Discogs: Joy Division “Transmission” (example matrix/runout with “A Porky Prime Cut”)

- Led Zeppelin IV “Pecko/Pecko Duck” explainer (context for the inscriptions)