Crown of Creation (1968): A Post-Mortem of the Summer of Love

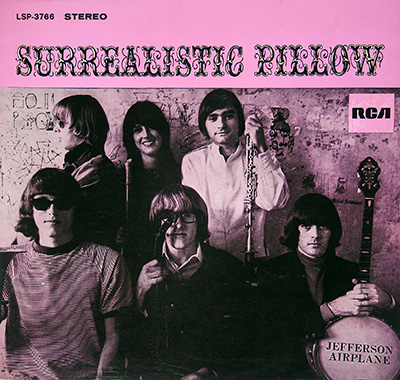

Drop the stylus on LSP 4058 and the room immediately feels smaller. There is no "warm welcome" here. By 1968, the Airplane had stopped trying to be your friend and started acting like your conscience, or perhaps just the person shouting at you in a crowded hallway. The fourth album arrives not as a collection of songs, but as a dense, slightly paranoid update from the front lines of a cultural nervous breakdown. It’s bigger than their previous efforts, certainly, but it’s a cold kind of big—meticulously engineered at RCA Hollywood between February and June, where the band spent four months polishing a mirror to show the world its own frayed edges.

I’ve been staring at a German pressing lately—Made in Germany stamped with that clinical European authority. It suits the music. There’s a precision to the chaos that feels almost industrial. The harmonies are still there, but they’ve lost their "Miracles" sweetness, replaced by Grace Slick’s steel-plated delivery. When she sings, it’s less of an invitation and more of a directive. You can practically hear Jorma Kaukonen in the corner of the studio, ignoring the producer and coaxing jagged, geometric shapes out of his Gibson ES-345. He isn't playing blues licks; he’s sketching a map of a city that’s about to burn down. Jack Casady’s bass doesn’t sit in the mix so much as it prowls through it, heavy and ominous, like something moving beneath the floorboards.

The tracklist is a study in friction. "Lather" is a cruel little piece of theater, a birthday song that feels like a funeral for youth, complete with sound effects that should be kitschy but end up feeling lonely. Then there’s the David Crosby problem. "Triad"—a song the Byrds were too polite (or too scared) to touch—is tucked away here like a quiet scandal. It’s a slow-burn argument for a three-way relationship, delivered with a straight face that still feels provocative decades later. It’s followed by "Greasy Heart," which hits with a sneering, garage-rock snap that reminds you why Slick was the most formidable woman in any room she entered. The whole thing culminates in "The House at Pooneil Corners," a track that doesn't so much end as it collapses into a feedback-heavy realization that the party is over and the bill is due.

There’s a bit of light-fingered literary theft in the title track, too. Paul Kantner lifted the lyrics almost verbatim from John Wyndham’s 1955 novel "The Chrysalids" without bothering to mention it on the sleeve. It’s a bold move, or perhaps just a lazy one, but it fits the era’s "everything belongs to everyone" ethos, even if the copyright lawyers eventually disagreed. The album reached #6 and went gold, proving that in 1968, you could still get the public to buy a mushroom cloud if you packaged it correctly. Looking at the orange RCA Victor label spinning at 33 1/3, you realize this isn’t just "psychedelia." It’s the sound of the door locking behind you. It’s brilliant, it’s difficult, and it’s entirely uninterested in whether you’re having a good time or not.