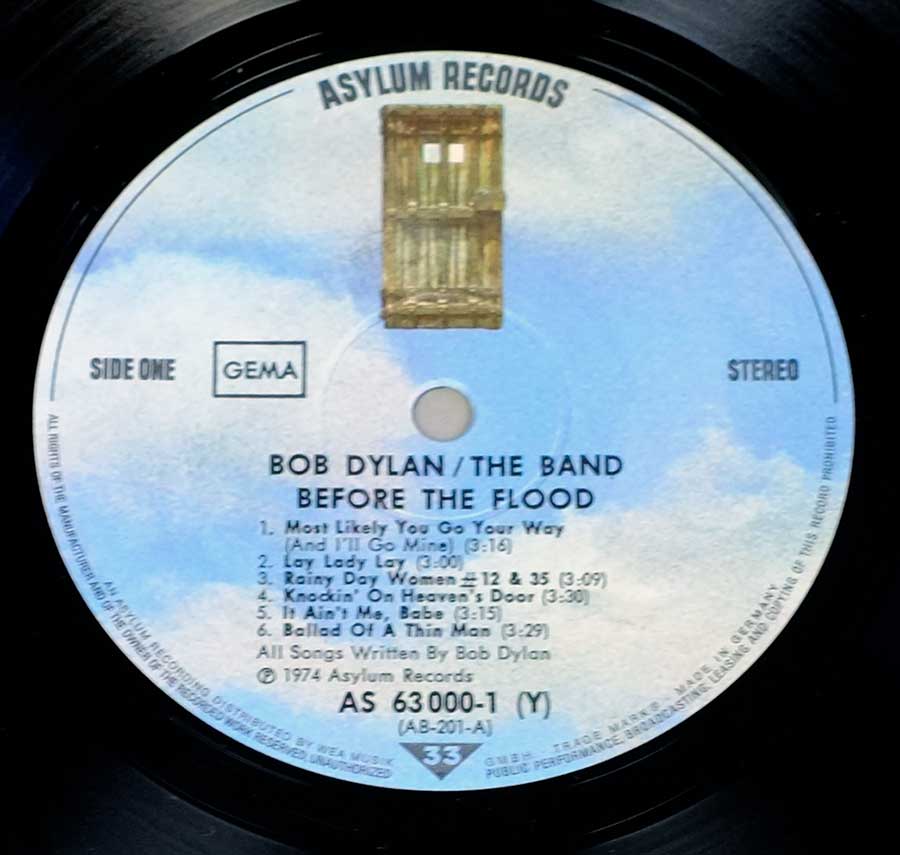

Bob Dylan / The Band — “Before the Flood” Album Description:

Return of the prodigal headliner. After eight years off the road, Dylan walks back into the spotlight with The Band as both engine and brake, filling sports arenas with a roar that turns folk aphorisms into stadium signals. Released in June 1974 on Asylum in the U.S., the double live set captures the heat and hustle of that winter’s short, explosive tour.

Historical context: a tour like breaking news

Dylan’s first full-fledged tour since 1966 had the urgency of a bulletin—mail-order only tickets, demand off the charts, prices nudging the top end for the era. It wasn’t just a concert series; it was a referendum on whether the most written-about songwriter could still command a mass audience on his own terms.

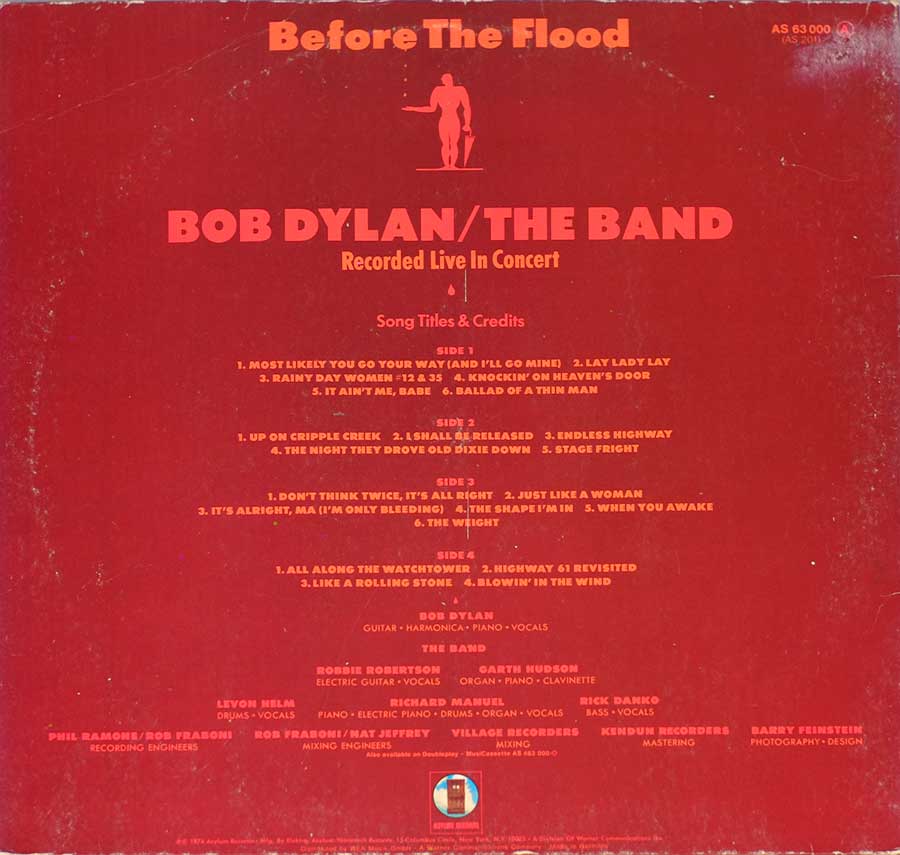

What’s on tape: the Forum fever

The album is largely drawn from the final Forum shows in Inglewood, February 13–14, 1974, with one detour to New York—“Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” from January 30 at Madison Square Garden. That focus gives the record a compressed, end-of-tour intensity: tempos up, edges sharpened, vocals projected like headlines.

Show architecture: three acts and a benediction

The nightly arc ran like theater: Dylan with The Band to open; The Band alone; intermission; Dylan solo with guitar and harmonica; a final electric charge with the whole crew; “Like a Rolling Stone” as civic ritual; “Blowin’ in the Wind” as the soft-focus coda. The design made contrast the star—private voice versus public roar.

Top musicians: the gears behind the grind

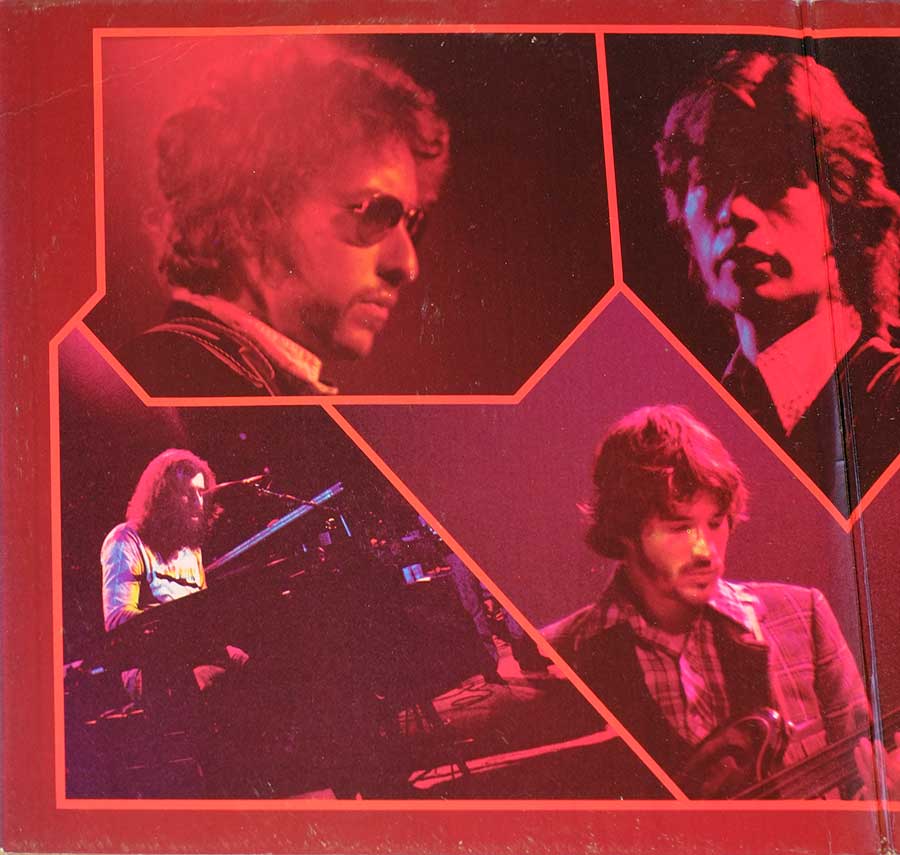

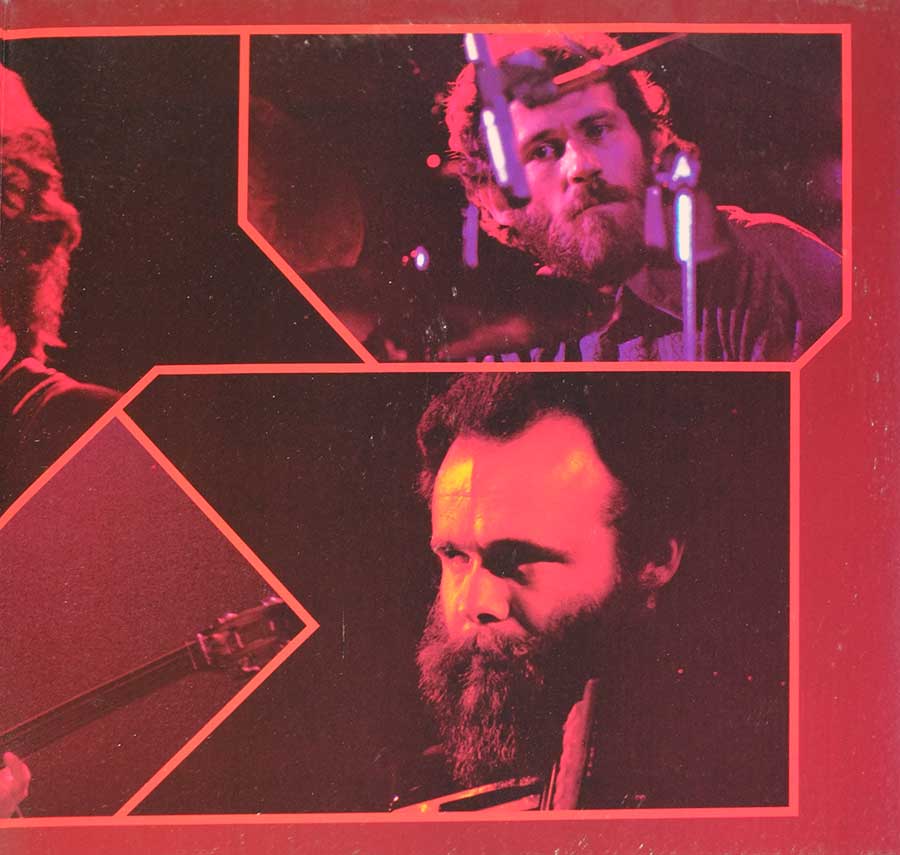

On the Band side, Robbie Robertson’s stinging lines thread through the noise; Levon Helm makes backbeat into plot; Rick Danko’s bass and high harmony keep the songs buoyant; Richard Manuel’s piano and weary tenor bring ache; Garth Hudson’s Lowrey, clavinet, and reeds sketch the margins in neon. Dylan sings, howls, and jabs on guitar, harp, and piano—provoking the band like a columnist poking an editor.

Musical exploration: rewriting the familiar

“It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” stiffens into a march; “Highway 61” turns metallic and mischievous; “Ballad of a Thin Man” is shouted like a verdict. These are not facsimiles from the ’60s—they’re 1974 arena performances, loud and impatient, the songs rebuilt for reach rather than reverie. Contemporary reviewers split: some heard epochal force, others clutter and overemphasis. That tension—the thrill of volume versus the loss of intimacy—is the album’s central argument.

Band historical currents

Studio allies turned equal partners, The Band had just cut “Planet Waves” with Dylan, then stepped into co-billing on the road. On record label chessboards, Dylan was briefly off Columbia and on Asylum, an interlude that ends soon after this set; The Band continued their own path via Capitol. The album freezes that moment of shifting contracts and steady camaraderie.

Controversies and climate

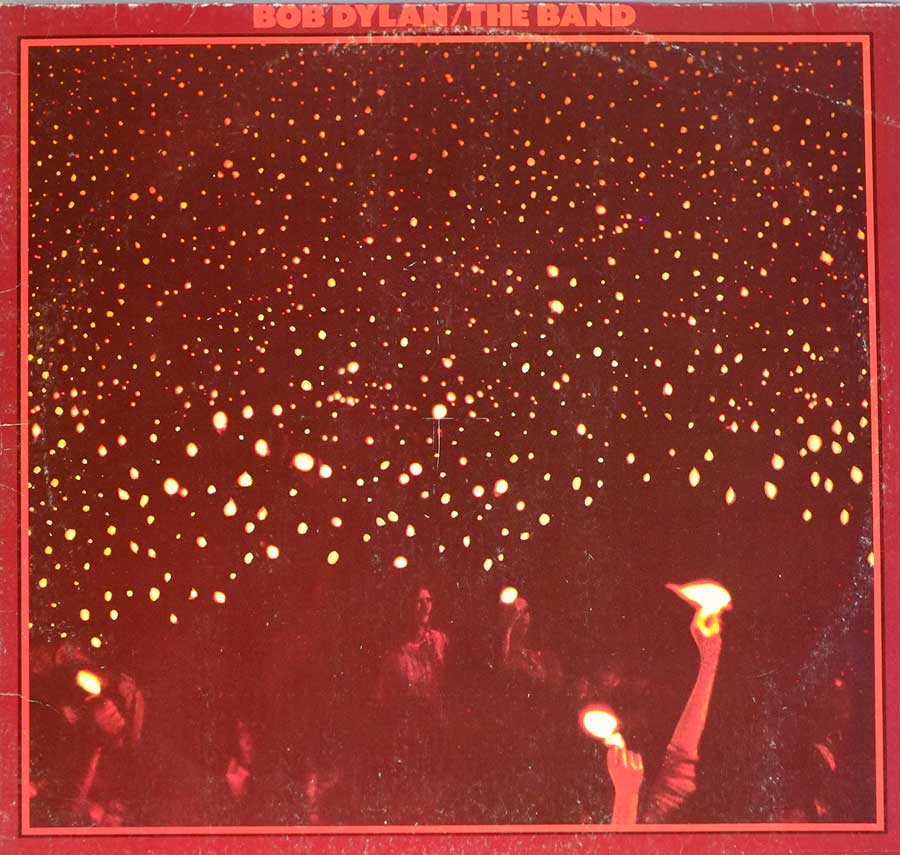

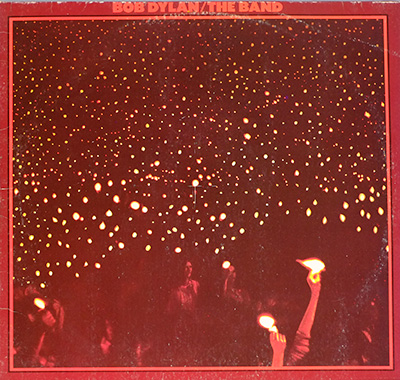

Ticket pricing drew heat; so did the scale—sports arenas and scalpers in the headlines, the old folk-club intimacy traded for spectacle. In the Bay Area, Mimi Fariña publicly scolded Dylan over rumored charitable allocations and the optics of activism versus commerce; Dylan dismissed the rumors with typical side-spin. Outside the debates, the shows felt like civic gatherings where matches flared for encores and the crowd sang as if reading along.

Songs as reportage

“Like a Rolling Stone” arrives not as nostalgia but as a town-hall chant; “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” becomes The Band’s own headline set-piece; “Up on Cripple Creek,” “Stage Fright,” and “The Weight” are local color between Dylan’s dispatches. The running order feels less curated than chased—go where the energy breaks, then ride it to the next corner.

Reception: critics at the barricades

Robert Christgau called it the craziest, strongest rock-and-roll ever put to tape, while Rolling Stone’s Tom Nolan heard more blare than bloom. The split verdict reads like the record itself—one part exclamation, one part question mark—yet it landed high on the charts and in year-end polls, proof that controversy and communion can share the same groove.

Why it matters musically (without the museum glass)

“Before the Flood” isn’t a field recording of authenticity; it’s a document of scale: how a songwriter who once whispered truth into coffee cups learned to shout it across basketball courts, and how a band of Southern Canadian storytellers made huge rooms feel like corners of a bar. The record is argument and answer, test and testimony—the sound of songs built to carry past the rafters and out into the night.