Album Description:

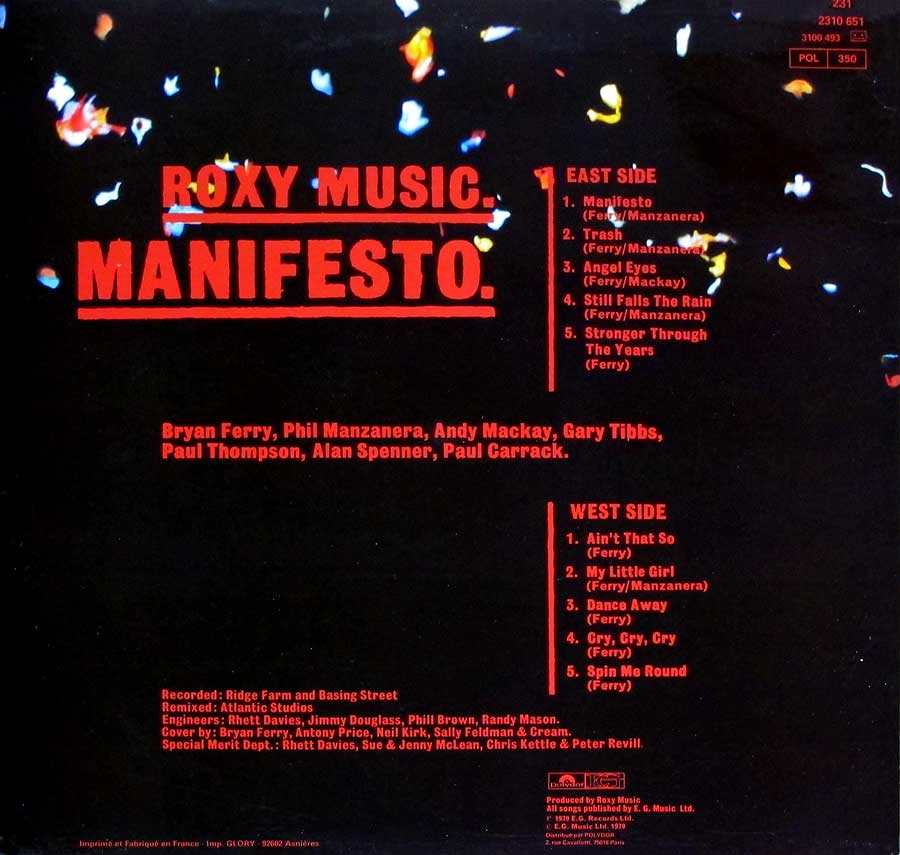

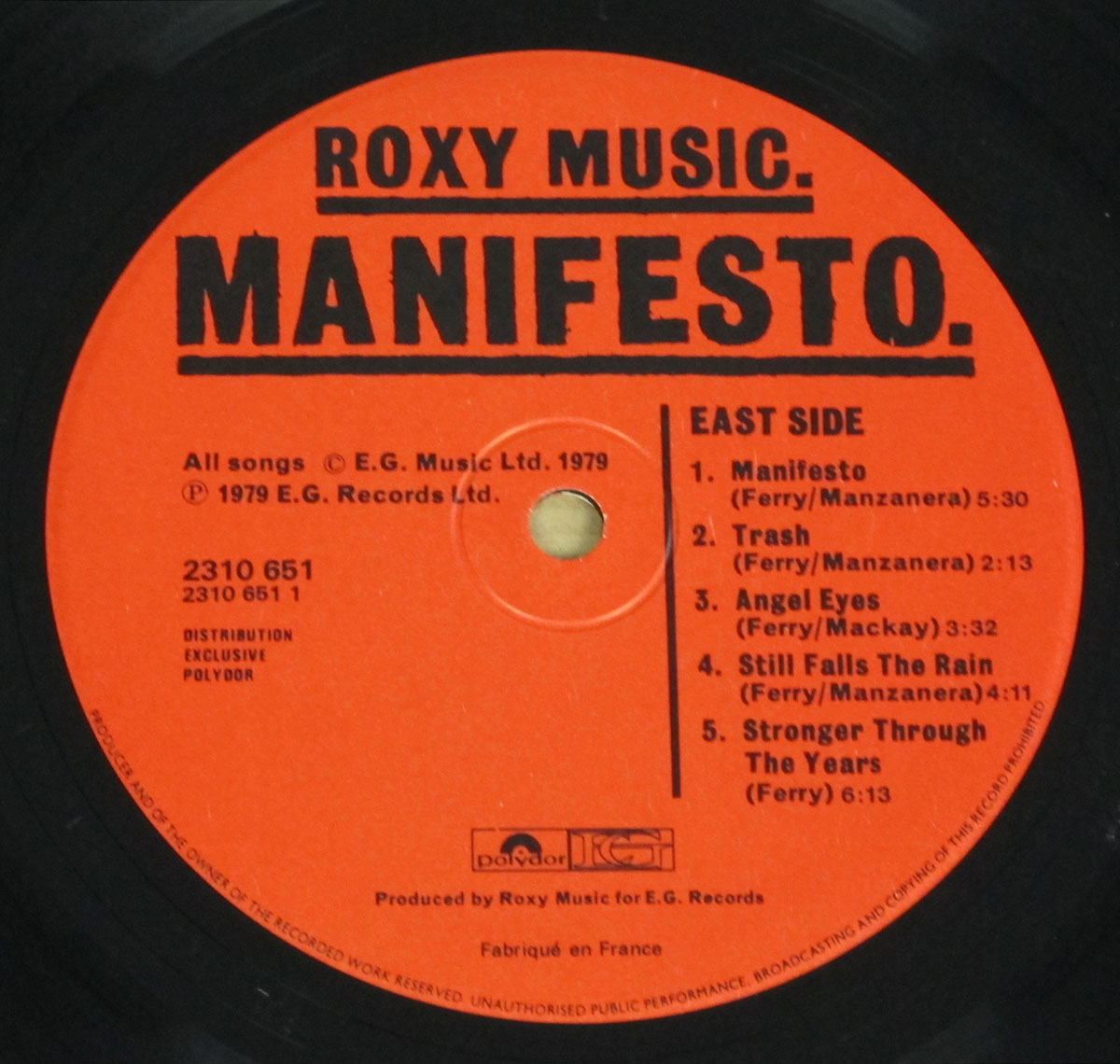

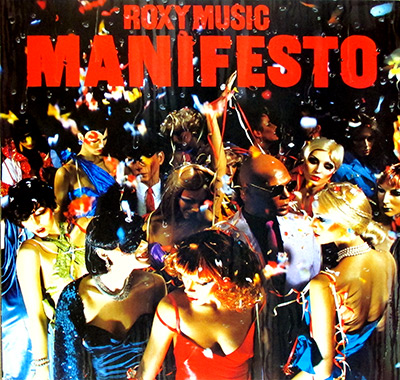

ÒManifestoÓ arrived in early 1979 as Roxy MusicÕs return to album-making after a four-year pause since ÒSiren.Ó Cut at Ridge Farm and Basing Street and remixed at Atlantic Studios, it reunites the core quartetÑBryan Ferry, Phil Manzanera, Andy Mackay and Paul ThompsonÑwhile folding in select guest players. The record balances the bandÕs art-rock imagination with a sleeker, dance-aware pulse that would define their next phase.

The historical moment

The late 1970s were turbulent and fast-moving: punk had blown open the UK scene, post-punk and new wave were taking shape, and dance floors were dominated by disco and sophisticated R&B. ÒManifestoÓ lands right in that crossoverÑa veteran art-rock group reengaging a landscape now occupied by Talking Heads, Blondie, The Police, Japan, Ultravox and a still-shape-shifting David Bowie. RoxyÕs answer is not retreat but reinvention: urbane songcraft, sharper grooves, and immaculate studio finish.

Genre position and peers

File the album under art rock and pop-rock with new-wave economy and a conscious nod to contemporary dance music. Where early Roxy mixed glam volatility with avant pop, ÒManifestoÓ favors space and polish: ManzaneraÕs guitar cuts and curls rather than screams; MackayÕs oboe and sax thread melody and atmosphere; FerryÕs croon steers everything toward elegant, metropolitan pop. In spirit and surface sheen, it sits comfortably alongside albums by Blondie and Japan, yet retains RoxyÕs idiosyncratic harmonies and textural wit.

Musical exploration on the record

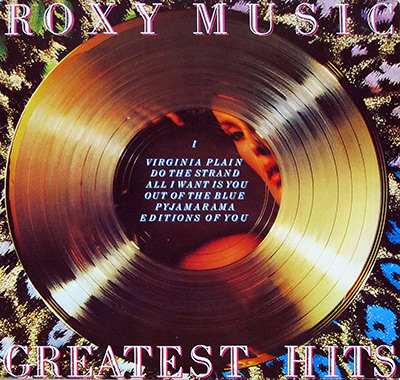

The title track opens like a manifesto in soundÑslow-building, noir and cinematicÑbefore snapping into a taut groove. ÒAngel EyesÓ weds riff-rock to the eraÕs dance sensibility (later re-cut as a sleeker, club-ready single), while ÒDance AwayÓ distills RoxyÕs urbane heartbreak into one of FerryÕs most effortless melodies. ÒStill Falls the RainÓ and ÒStronger Through the YearsÓ stretch out with modal touches and deep, hypnotic rhythms; the latter lets the rhythm section breathe while Mackay and Manzanera sketch long-form arcs rather than short solos. Across the album, arrangements prize contour and feel over spectacleÑhooks delivered with restraint, rhythm sections recorded for glide, not grind.

Key people behind the board

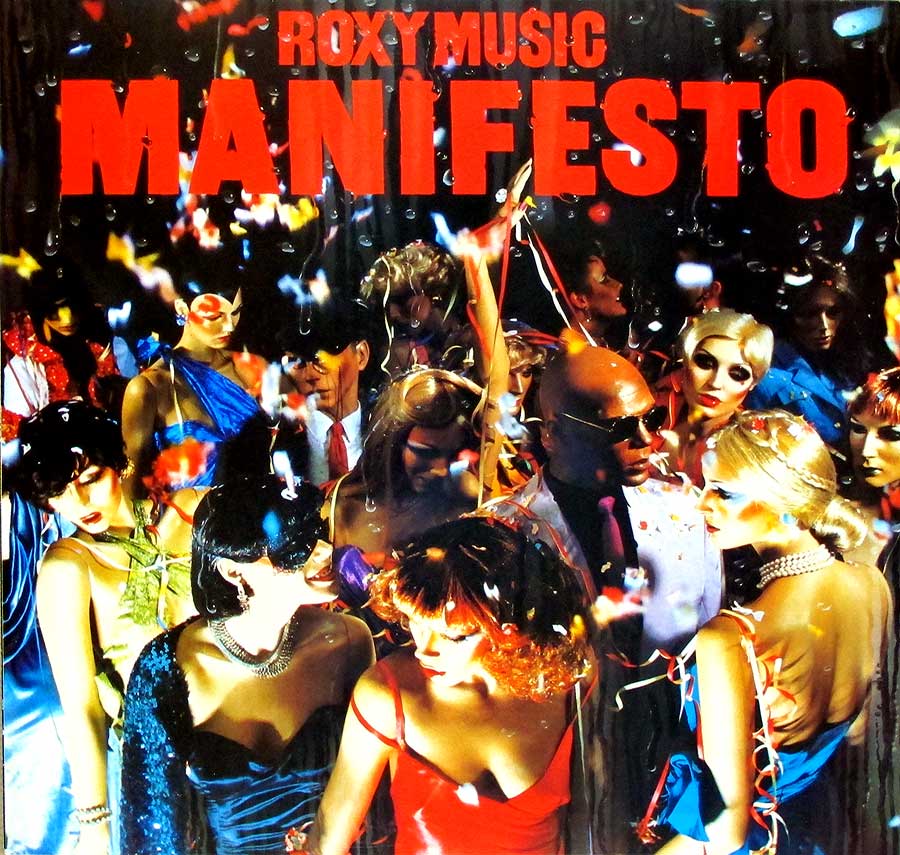

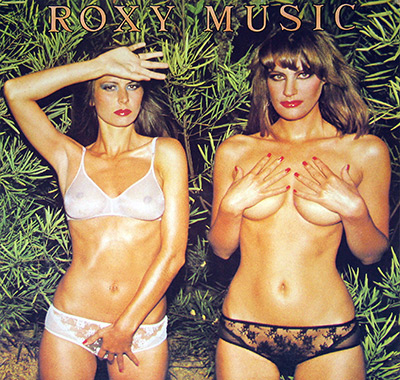

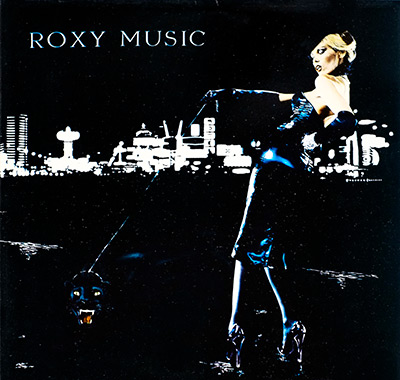

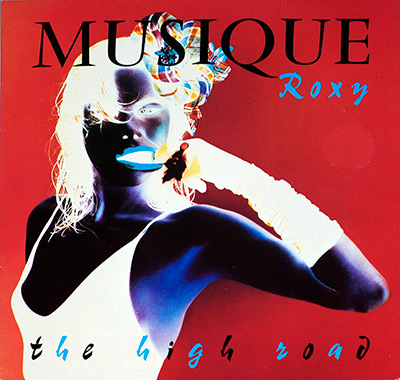

Roxy Music produce themselves, leaning on a trusted studio team. Sound Engineers Rhett Davies, Jimmy Douglass, Phill Brown and Randy Mason shape the recordÕs clarity and punch. The sessions take place at Ridge Farm and Basing Street; remixes at Atlantic Studios add extra gloss. The visual world is equally curated: Bryan Ferry steers the cover concept and design with Antony Price; photography by Neil Kirk, with artwork support from Sally Feldman and Cream, ties music and fashion into the same luxurious frame.

Band story and line-up shifts

Formed in 1971, Roxy Music originally featured Bryan Ferry, Andy Mackay, Brian Eno and Graham Simpson, with Paul Thompson and later Phil Manzanera locking the classic engine. EnoÕs 1973 departure and Eddie JobsonÕs mid-Õ70s tenure pushed Roxy through several evolutions before the mid-decade hiatus. For ÒManifesto,Ó the returning core drafts a small cadre of specialists: Paul Carrack adds supple keyboards, Richard Tee contributes piano elegance, and the bass chair is shared by Alan Spenner and Gary Tibbs. Rick Marotta provides additional drums alongside Paul Thompson, whose muscular swing remains a defining presence.

Points of debate and reception

Two flashpoints accompanied the album. First, the stylistic pivot: longtime fans of the jagged early records read the new smoothness and dance-friendly rhythms as a departure, sparking familiar Òsellout vs. evolutionÓ arguments. Second, the single-focused revisions: ÒAngel EyesÓ was later re-recorded in a more overtly disco style and, on some later pressings, replaced the original LP versionÑfueling confusion (and heated preferences) about the ÒrightÓ mix. Both debates underscore the recordÕs central tension: a band famed for risk and glamour choosing to modernize without surrendering identity.

Why ÒManifestoÓ matters musically

Beyond hits, the album demonstrates a craft shift: economy in arrangements, rhythm sections recorded for glide, and vocals written as architectureÑevery consonant supporting the groove. It is the bridge between the experimental ferocity of early-Õ70s Roxy and the sumptuous, adult pop of their early-Õ80s work, proving that art rock could move bodies as deftly as it teased minds.

Anecdote Ñ ÒDonÕt BlinkÓ

They were twins, ushered into the studio after midnight, told to Òblend in.Ó Around them stood a small army of mannequins: lacquered smiles, frozen wrists, names written in pencil on masking tapeÑÒRuby,Ó ÒVera,Ó ÒNo. 7.Ó A stylist dusted the twinsÕ shoulders, then stepped back to judge whether they looked human enough to pass for plastic, or plastic enough to pass for human.

ÒDonÕt blink,Ó the photographer joked, and the room obeyed. Lights flared, fans hummed, and the bandÕs music leaked from a distant control roomÑjust loud enough to set a rhythm for standing perfectly still. The twins stared ahead, counting silently. One, two, threeÉ clap. Flash. The click of the shutter landed like a metronome.

Halfway through, a mannequin in sequins tipped over with a graceful, catastrophic wobble. Nobody moved for a secondÑthen everyone moved at once. An engineer caught the head; a makeup artist caught the hand; one twin stifled a laugh that shook her shoulders. ÒReset,Ó called the photographer, and the twins exhaled in unison, as if they shared one pair of lungs.

When the last roll of film snapped free, the crew applauded themselves for surviving an evening of motionless work. The twins were thanked, offered lukewarm tea, and slipped out into the London chillÑhair sprayed into small helmets that made the night air bead and run.

Months later, they stood outside a record shop window, staring at the sleeve. There they were: two nearly-living shapes among the unmoving many. A passerby said, ÒGreat ideaÑmannequins.Ó One twin smiled and said nothing. The other blinked, just once, and for a heartbeat the whole tableau seemed to shiftÑlike the photograph was breathing back.