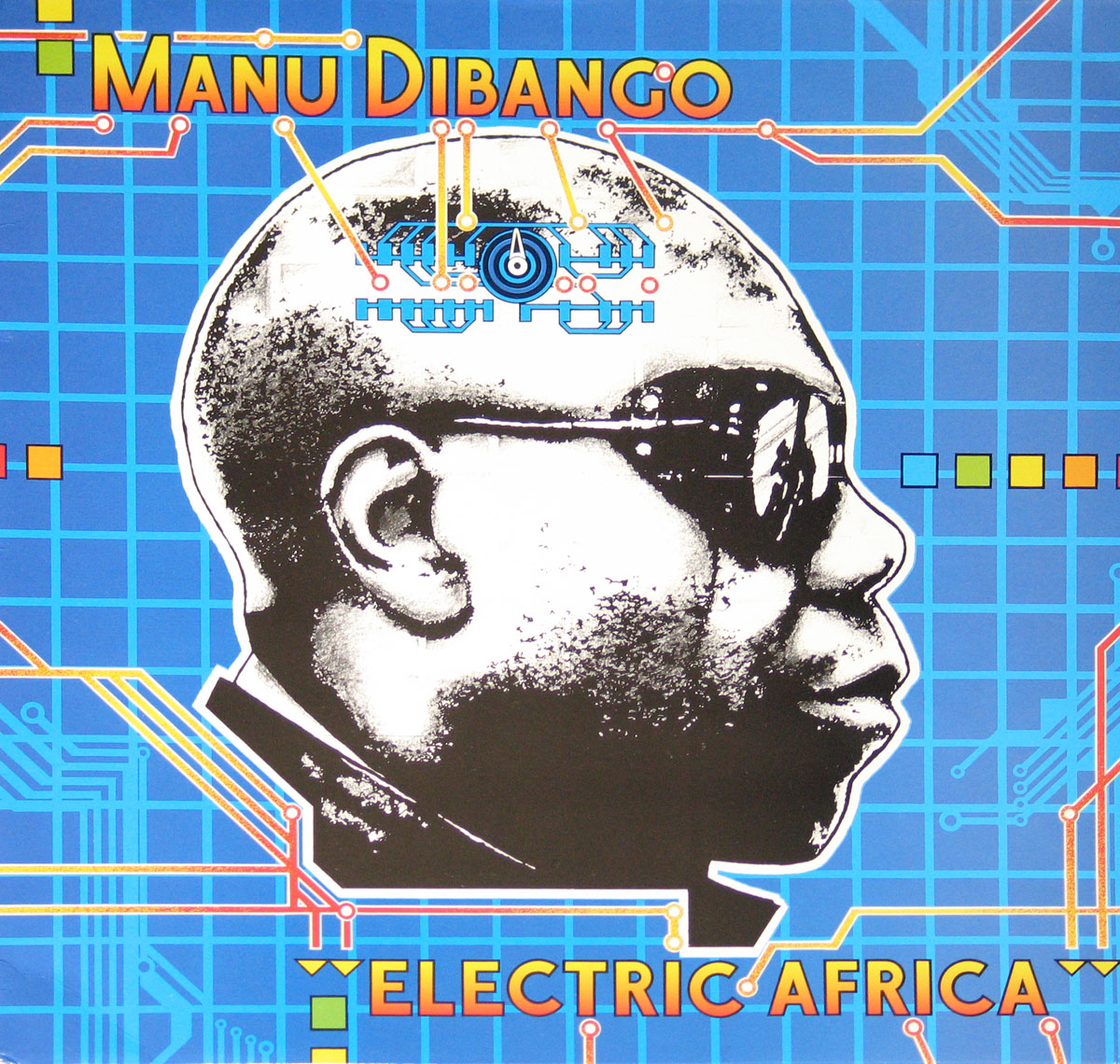

"Electric Africa" (1985) Album Description:

"Electric Africa" is Manu Dibango at the exact point where tradition stops being polite and starts getting interesting: a Cameroon-born sax voice wired into mid-80s studio electricity, with Bill Laswell steering the session like a downtown traffic cop who actually enjoys the chaos. This is Afro-jazz that refuses to sit still, built for movement, built for a room with speakers, and built with the confidence of an artist who knows his roots and still wants to take the elevator to the future.

Where this record sits in 1985

1985 is the year pop goes glossy, drum machines go everywhere, and “fusion” stops meaning a jazz club argument and starts meaning a production strategy. In Europe, especially Paris, African and Caribbean musicians are colliding with new studio tech and new label pipelines, and the result is less “museum” and more “street at night.” "Electric Africa" lands right in that intersection: African rhythm logic meeting a modern studio that can edit, loop, punch in, and amplify attitude.

Cameroon in the mid-80s, and why it matters here

Cameroon in the mid-80s is politically tightening and reorganizing under Paul Biya’s early presidency, with the ruling party structure being reshaped in 1985. That kind of national atmosphere doesn’t write melodies for you, but it does push artists to think hard about identity, language, and what “home” even means when your working life is international. Dibango’s music doesn’t read like a manifesto; it reads like a passport with a lot of stamps and a sax line that never forgot where it began.

The genre: Afro-jazz with a plug in the wall

Call it Afro-jazz, call it Afro-funk, call it “jazz that learned to dance without asking permission.” The core idea is simple: African rhythmic architecture, jazz phrasing, and a production approach that treats the studio as an instrument, not a tape recorder. The sax doesn’t just solo; it leads, comments, teases, and sometimes just flat-out sings over grooves designed to hypnotize.

On records like this, the big musical move isn’t “adding electronics.” The move is letting electronics become part of the rhythm section, so the groove stays hard even when the instrumentation shifts. That’s why tracks can stretch, breathe, and still feel locked in.

This is not “jazz plus Africa.” It’s a modern studio building a new room where both of them can talk at full volume.

Musical exploration: what you actually hear happening

The album plays with contrast: organic percussion against precise programmed time, long melodic lines against tight repetitive motifs, and bright horn tone against darker, thicker low-end production. Dibango’s sax is the human fingerprint on top of a machine-era grid, and that tension is the hook. The grooves keep cycling, but the phrasing keeps arguing, which is exactly why it stays alive.

- Extended track shapes: themes develop like conversations, not radio edits.

- Rhythm layering: hand percussion and programmed elements share the same seat.

- Melodic authority: the sax isn’t decoration; it’s the narrator.

- Studio-as-instrument: texture and placement matter as much as notes.

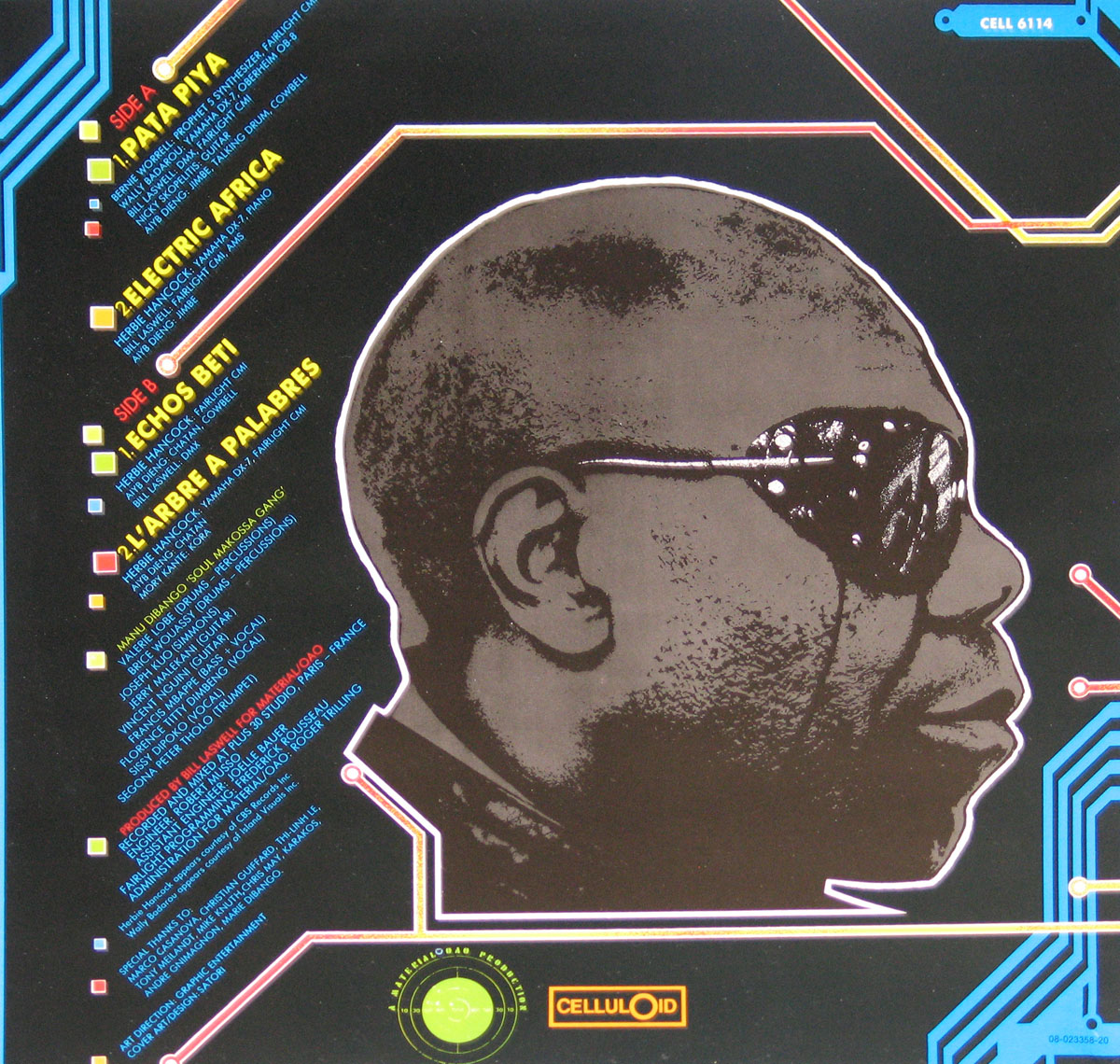

Key people behind the sound

Bill Laswell’s production is the hinge: he brings a composer's sense of structure and a producer’s sense of pressure, keeping the music open while making it hit. Engineering at Paris’s Studio Plus 30 gives the record its clean punch and spatial depth, the kind that makes percussion speak and lets the sax sit forward without sounding pasted on. Players from Laswell’s circle add the sharp edges: guitar that can slice or shimmer, percussion that knows how to carry a long groove, and keyboard colors that widen the frame.

Credits matter here because this is a meeting of worlds, not a one-man postcard. When the rhythm section is part human and part circuitry, the producer and engineer aren’t “support,” they’re co-authors of the soundstage.

Manu Dibango’s road to this session

Dibango isn’t a new face in 1985; he’s an artist who’s already lived inside multiple musical languages and learned how to switch them without losing his accent. Schooling in France as a teenager sets the trajectory: Europe becomes the long base, while Cameroon stays in the bloodstream. By the time he walks into a session like this, he’s not trying on identities; he’s stacking them.

Peers in the same neighborhood, same year

In the mid-80s, the wider scene is full of artists pulling African rhythm and jazz phrasing into modern contexts, each in their own dialect. Some lean harder into political urgency, some into dance-floor drive, and some into pure instrumental conversation. "Electric Africa" belongs to the branch that says: make it groove first, then let the ideas ride the groove like a wave.

- Fela Kuti and the Afrobeat continuum pushing long-form rhythm as a worldview.

- Hugh Masekela and other pan-African jazz voices carrying brass into contemporary production.

- The Paris-based “global groove” ecosystem where African, Caribbean, jazz, and post-punk scenes cross-pollinate.

Controversy (and the honest version of it)

"Electric Africa" didn’t detonate a tabloid scandal or trigger official bans. The friction is more subtle and more common: purists hearing the studio tech and calling it compromise, modernists hearing the tradition and calling it baggage. The record’s “controversy,” if you want to call it that, is the argument it starts about authenticity when the music is clearly designed to travel.

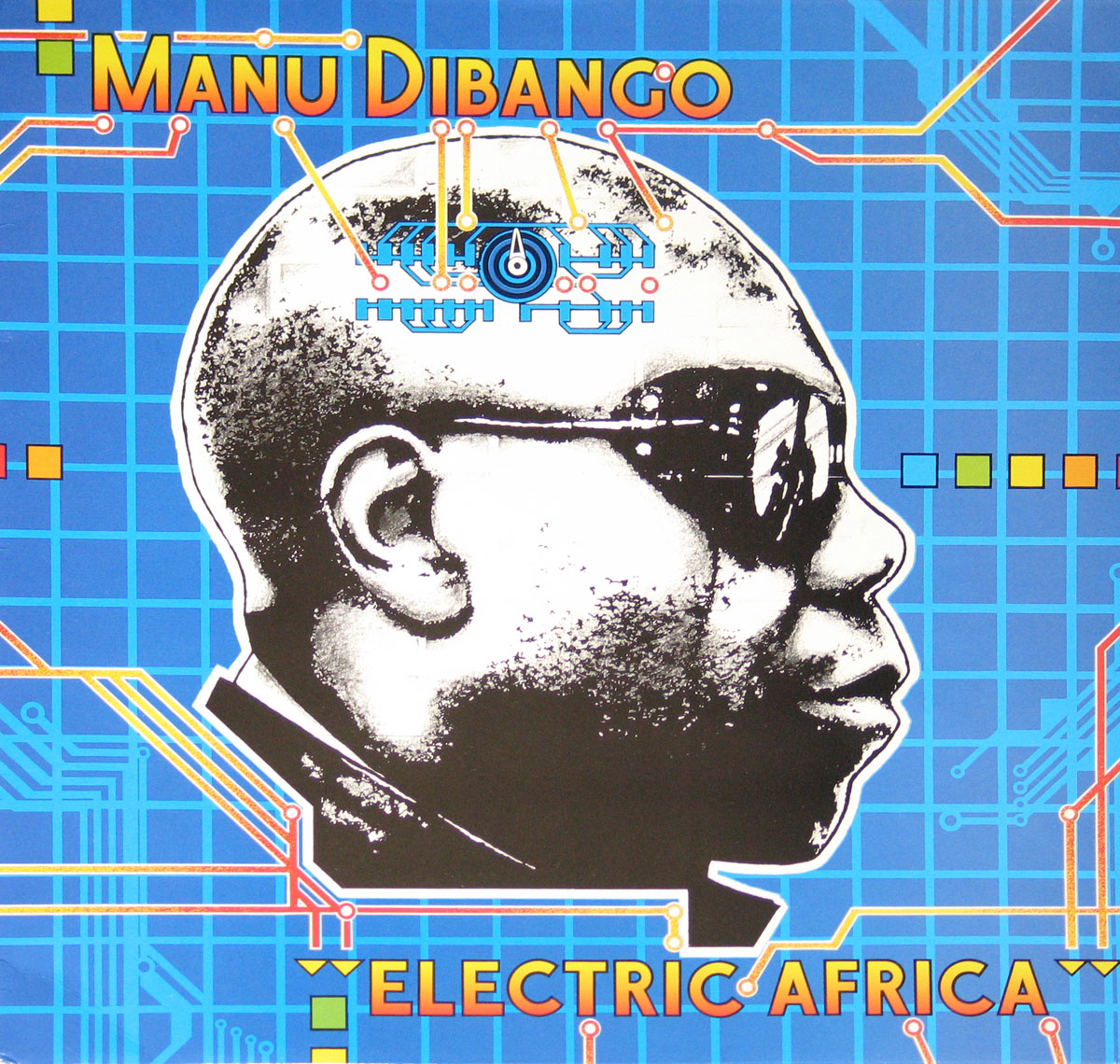

Images from this page

Front cover image used on this page.