"Ommadawn" (1975) Album Description:

"Ommadawn" is Mike Oldfield doubling down on the idea that a rock album can be built like a film: two long movements, no pop safety rail, and a whole lot of atmosphere that still hits with physical weight. Released in 1975 on Virgin Records and produced by Oldfield himself, it turns English progressive rock into something more global and more human, pulling in voices, pipes, brass, and drums without turning into a tourist brochure. The headline is simple: one person, an absurd range of instruments, and a stubborn refusal to trim the edges for radio.

Where Britain Was in 1975

England in 1975 was running hot and tired: economic anxiety, labor tension, and a culture that felt like it was being renegotiated in real time. That pressure bled into music, especially the progressive scene, which had gotten big enough to be both ambitious and a target. Rock was no longer just rebellion; it was also business, spectacle, and a serious argument about what counted as art.

Progressive rock in that moment was at a pivot point: it could go grander, or it could collapse under its own cape. Bands in the same neighborhood were pushing long-form structures and studio craft, but the audience was starting to split between people who wanted more adventure and people who wanted less pretension. Oldfield doesn’t argue with either side here; he just builds his own weather system and lets everyone deal with it.

Prog Rock Around the Same Year

In 1975, the genre’s big names were still playing with scale and texture, and the studio was basically another band member. If you were hearing extended suites, shifting time feels, and layered keyboards and guitars in the air, you weren’t imagining it. The difference is Oldfield does it without a traditional band lineup, which makes the focus less about group personality and more about one composer’s internal logic.

- Extended-form rock was still normal in prog: long tracks, recurring themes, side-long structures.

- Folk and regional color was sliding into the genre more openly: pipes, recorders, unusual percussion, voices used like instruments.

- Studio layering was the craft flex: sound built in passes, not captured as a single performance.

The Big Musical Gamble

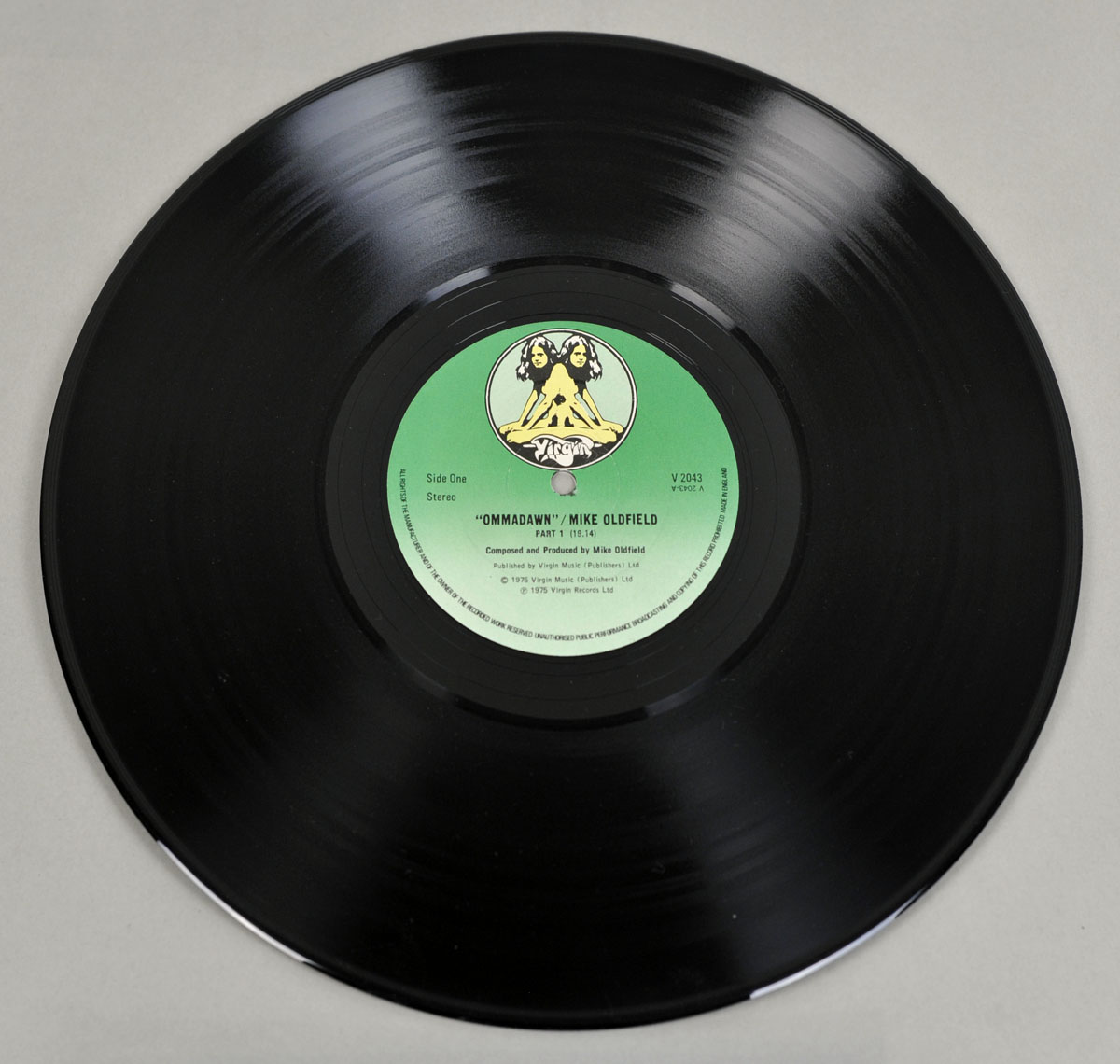

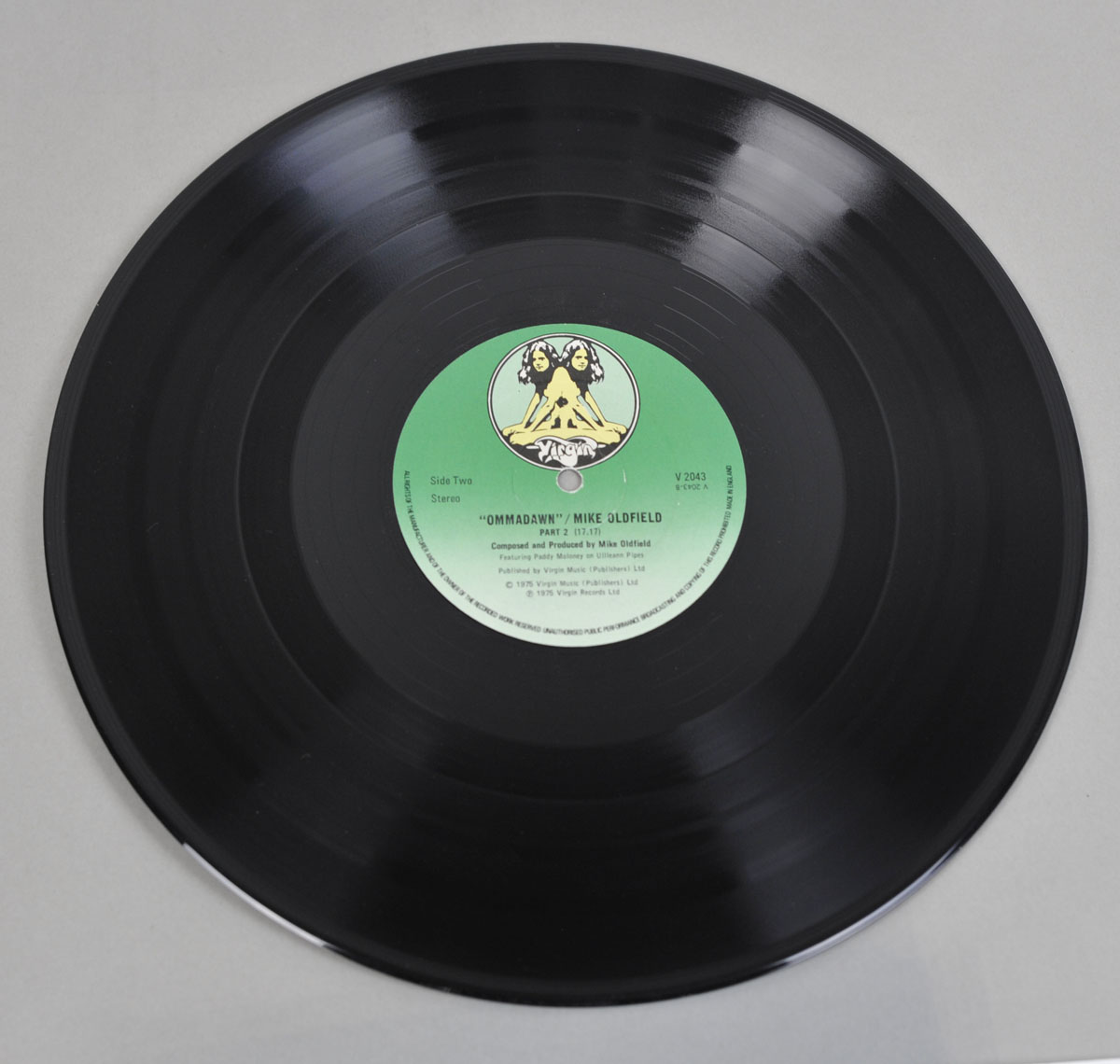

The track list tells you the plan: "Ommadawn, Part One" on side one, "Ommadawn, Part Two" on side two. That’s not minimalism; that’s commitment. Instead of a batch of songs, Oldfield gives you a pair of journeys where themes evolve, disappear, and come back wearing different clothes.

The core sound is Oldfield as a one-man instrument factory: acoustic and electric guitars, basses, keys, percussion, and synthesizers, stacked like architecture. The mood shifts fast, but not randomly; bright folkish passages can turn into darker, heavier surges, then lift again into choral warmth. The album keeps reminding you that “progressive” isn’t about complexity for its own sake, it’s about motion.

It plays like a suite, but it breathes like a late-night session: disciplined structure, sweaty emotion.

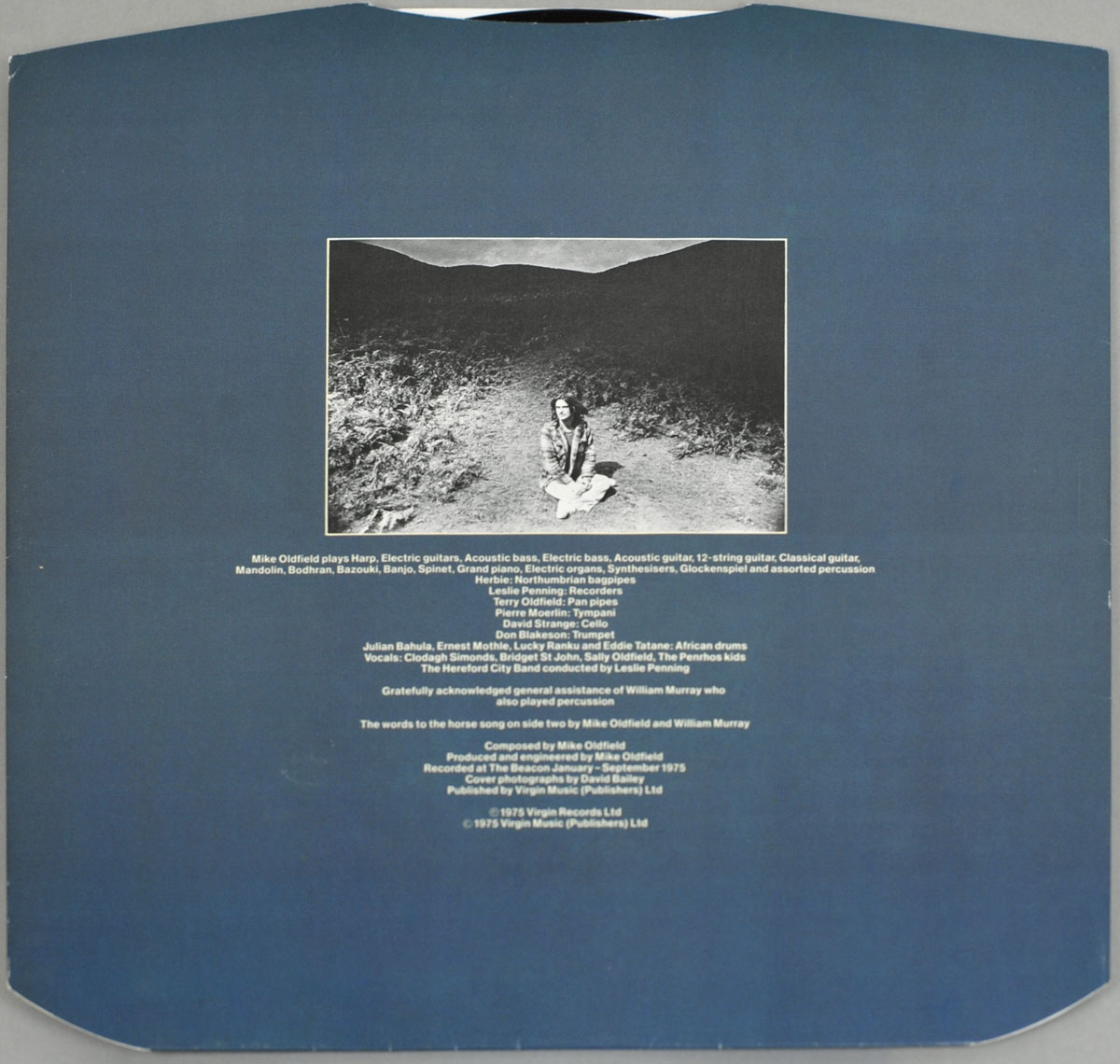

Key People on the Recording

Oldfield is the producer and the main engine, handling an extreme list of instruments and vocals while keeping the whole thing coherent. That kind of control can turn sterile, but here it stays tactile because the guest players don’t feel like decoration. They show up when the music asks for them, and they change the room.

- Mike Oldfield – producer; guitars, keys, percussion, synthesizers, vocals, and more

- Leslie Penning – recorders; also conducts The Hereford City Band

- The Hereford City Band – brass

- Paddy Moloney – uilleann pipes

- Jabula (Julian Bahula, Ernest Mothle, Lucky Ranku, Eddie Tatane) – African drums

- Pierre Moerlen – timpani

- Sally Oldfield, Clodagh Simonds, Bridget St John, and others – vocals

- Don Blakeson – trumpet

- David Strange – cello

There’s even an honest little footnote that tells you how these sessions went: Herbie’s Northumbrian bagpipes were recorded but unused on the final album. That’s not trivia; it’s a snapshot of a composer editing a giant canvas, keeping what serves the piece and cutting what doesn’t. The confidence isn’t in adding more, it’s in knowing when to stop.

Oldfield’s Timeline Into This Album

By 1975, Oldfield wasn’t an unknown trying to get a band noticed; he was a solo artist with momentum and expectations. "Tubular Bells" put him on the map, "Hergest Ridge" proved it wasn’t a fluke, and "Ommadawn" is the move where he widens the palette rather than repeating the trick. Virgin Records is part of that story too, because the label’s early identity was tied to taking big swings on artists who didn’t fit neat categories.

Since this is a Mike Oldfield record, the “line-up changes” are less about who quit and more about who gets invited into the sound. The personnel list is the real band photo: pipes, timpani, African drums, brass, choral voices, and children’s vocals on "On Horseback." It’s a rotating cast built around one composer’s hands and head.

Controversy, Such As It Was

"Ommadawn" didn’t arrive with a scandal headline attached, and it didn’t need one. The friction was structural: two long parts, no conventional single, and a production approach that basically ignores radio formatting. For some listeners and gatekeepers, that was enough to count as “difficult,” which is the polite industry word for “we don’t know how to sell this without lying.”

There’s also the quiet controversy that always hovers over a record like this: the moment progressive rock becomes a culture-war argument about excess. In 1975, that debate was already brewing, and albums built from long movements were easy targets. Oldfield’s answer is to keep the music grounded in melody and pulse, so the ambition reads as craft instead of ego.

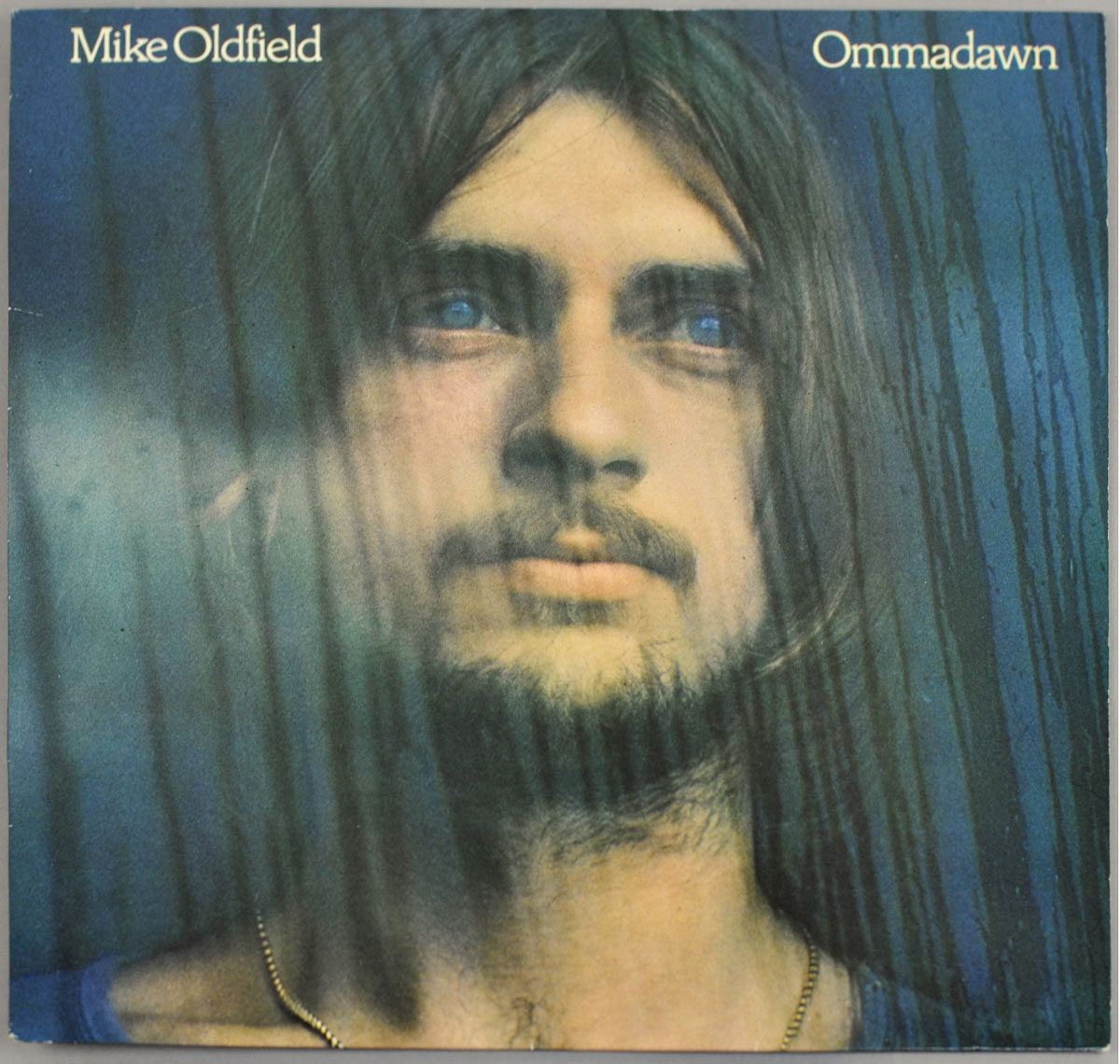

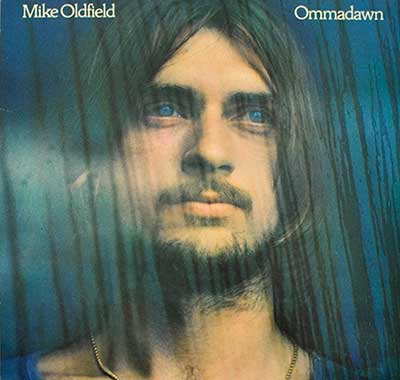

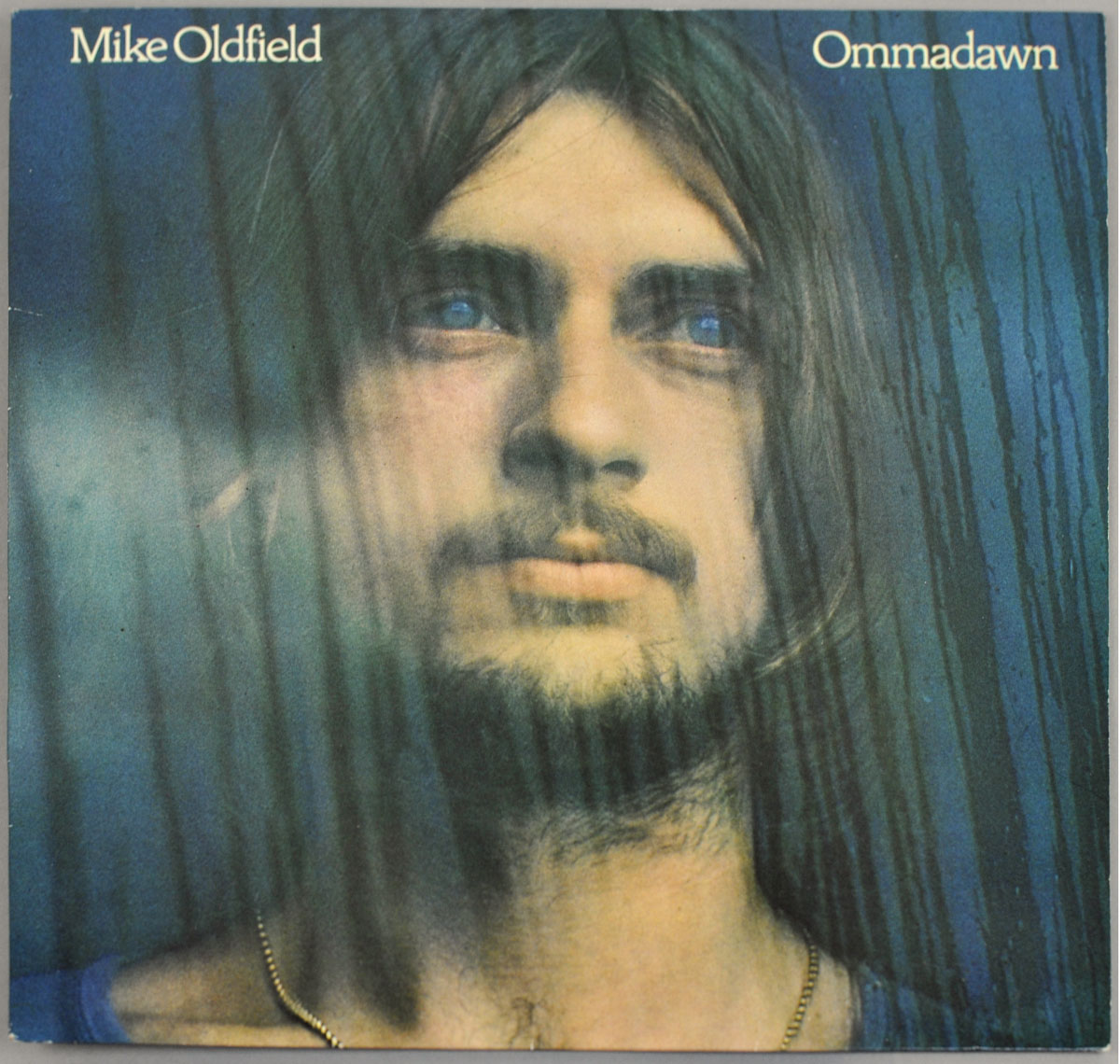

Visual Identity

The cover photography is by David Bailey, and it fits the album’s personality: clean, direct, and confident enough to let the music do the talking. That matters, because prog sleeves in the mid-70s could swing wildly between mythic fantasy and design concept art. Here, the visual presentation feels more like a statement of intent than a distraction.

How to Listen Without Overthinking It

The best way in is to treat each side like a narrative arc, not a track you can sample in the background. Listen for the way percussion changes the temperature, and how the pipes and voices don’t “guest-star” so much as redirect the whole piece. When the album swells, it’s not showing off; it’s building momentum the way a good band does live, except it’s happening inside the studio.

- Start with side one and follow the themes as they shift from acoustic intimacy to full ensemble weight.

- Notice the contrast points: folk color against electric force, tight rhythm against open-air drift.

- Let side two feel like the answer, not the sequel.