George Horn is the Bay Area's quiet mad scientist of lacquer, a Chief Mastering Engineer who kept Fantasy Studios (Berkeley) and CBS Studios (San Francisco) sounding expensive without turning everything into plastic. I follow his trail from 1971 at Columbia/CBS (Coast Recorders), to Kendun Recorders in 1978, then the long Fantasy run from 1980 into the 2000s. In the Tom Hidley-designed mastering room built in the late 1970s, he cut and remastered a ridiculous spread: Charles Mingus and other jazz giants, plus rock lifers like Creedence Clearwater Revival, The Grateful Dead and Santana. In 2008 he opened his own Berkeley mastering room, still chasing clarity like it owed him money.

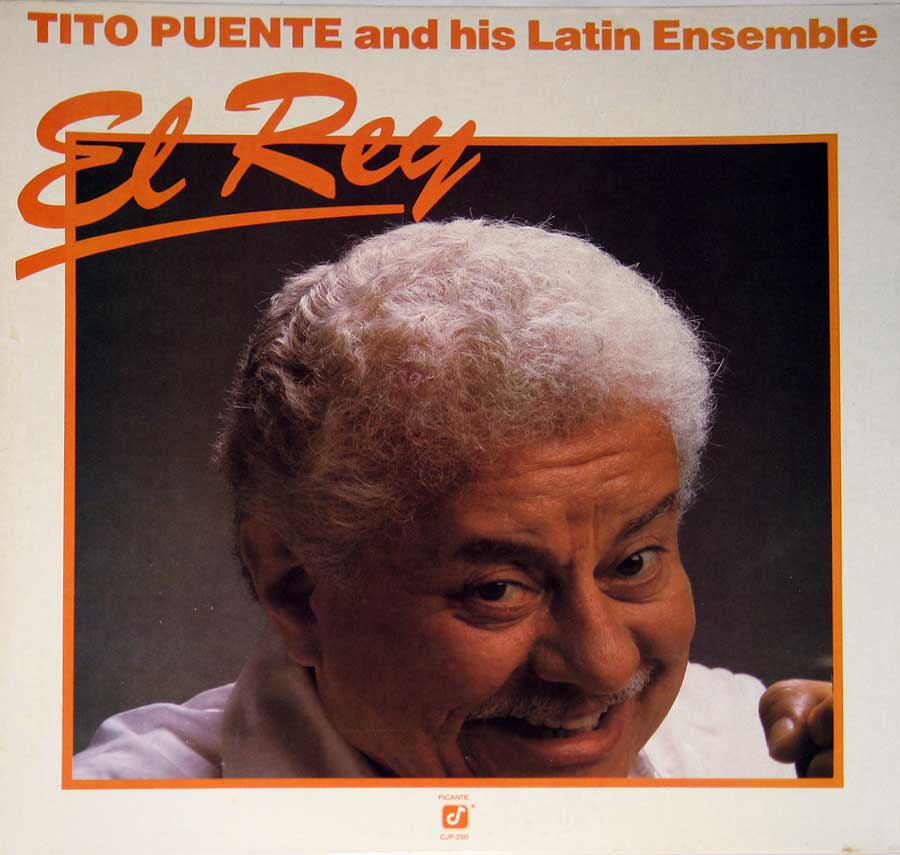

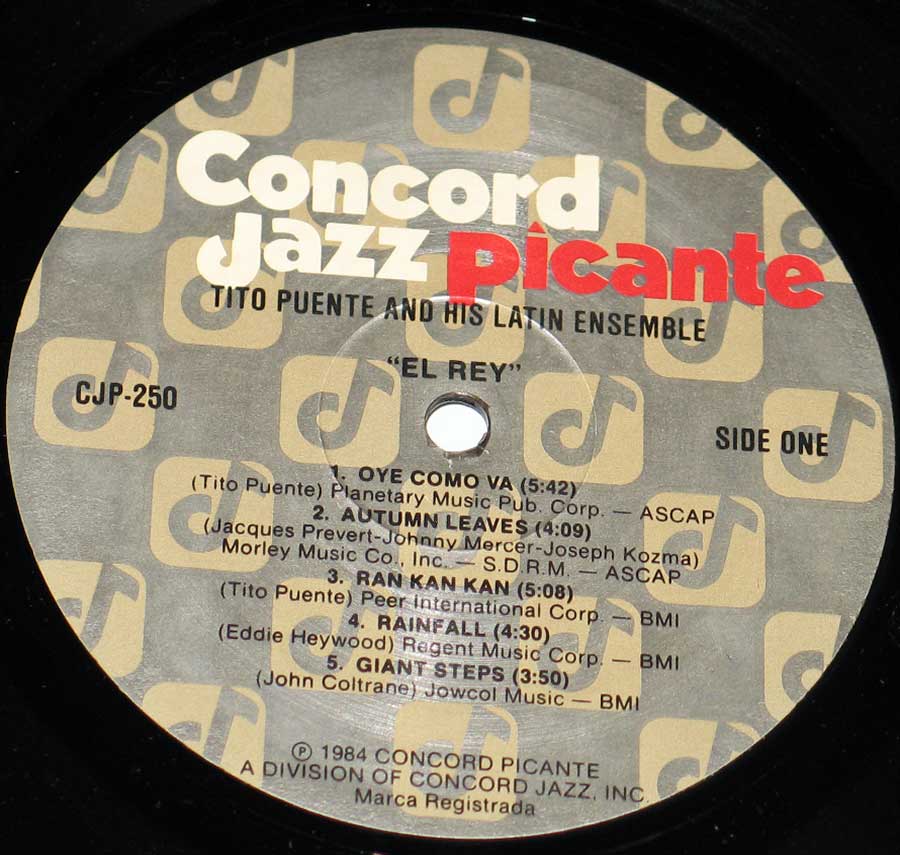

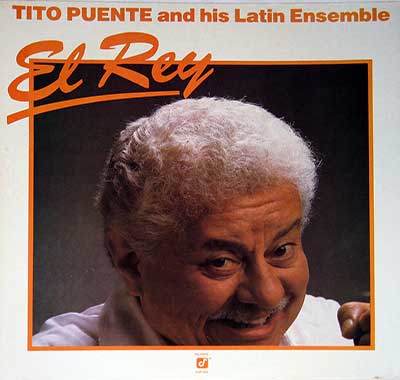

Tito Puente's ÒEl ReyÓ: A Pulsebeat of Latin Jazz in the American Soundscape Album Description:

In the spring of 1984, inside the hallowed walls of San Francisco's Great American Music Hall, a storm of rhythm, brass, and nostalgia erupted under the baton of Tito Puente. The album ÒEl ReyÓÑmeaning ÒThe KingÓÑisn't just a live recording; it's a proclamation. An uncompromising celebration of Latin jazz, it offers a snapshot of a musical form that's as American as it is Afro-Caribbean, as improvisational as it is militant in its danceability.

The Rhythms of Resistance

Emerging in an era where salsa and Latin jazz had been carved into the urban consciousness of cities like New York and San Juan, ÒEl ReyÓ represents the genre's return to unapologetic roots. This was not the overly-polished, crossover-obsessed Latin pop of the late '70s. This was mambo with muscles, cha-cha with teeth. Puente, often cast as a cultural diplomat, here allows the timbales to speak in a primal tongue, backed by a battalion of percussionists who play not behind him but beside him.

Jazz at a Crossroads

By 1984, jazz was splintering. Fusion had cooled. Traditionalists and progressives were at odds. ÒEl ReyÓ doesn't take sidesÑit declares independence. The tracklist is a tour through jazz's immigrant soul: from the standards like ÒAutumn LeavesÓ and ÒEquinoxÓ to Afro-Cuban stormers like ÒRan Kan KanÓ. In the middle of it all is Puente, both maestro and provocateur, taking the bones of the American songbook and wrapping them in conga skin.

The Band as Battalion

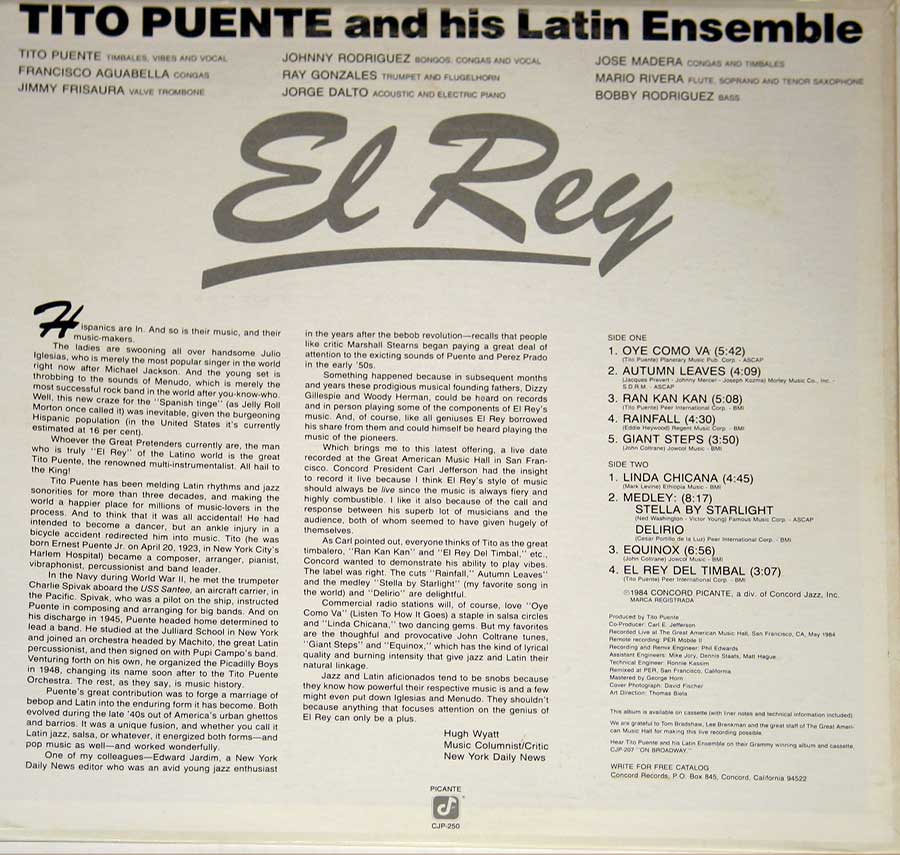

The lineup reads like a fantasy draft of Latin jazz warriors. Francisco Aguabella on congas delivers heartbeat rhythms forged in Yoruba ritual. Jorge Dalto lays down piano lines that flirt with bebop but answer to clave. There's Mario Rivera on flute, Ray Gonzales on trumpetÑmusicians who weren't just accompanying Puente but conversing with him. The solos explode not because they chase complexity, but because they surge with purpose.

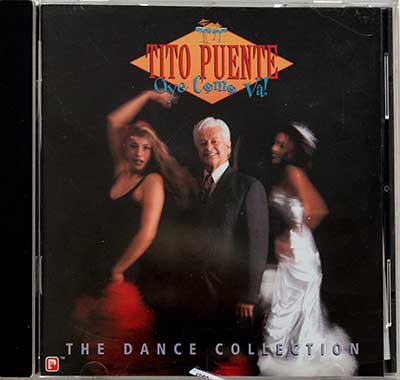

Oye Como Va – The Ripple Effect

A highlight of the album is ÒOye Como VaÓ, not simply as a tune but as an artifact. Originally recorded by Puente in 1963, the song was famously reimagined by Carlos Santana in 1970Ñan electrified version that brought the rhythm to Woodstock and beyond. But on ÒEl ReyÓ, the song returns home. Gone are the fuzz pedals and organ swells. What remains is rhythm and chant, stripped to essence. In this performance, we're reminded that Santana didn't create the vibeÑhe borrowed it from Puente.

Influence or Appropriation?

That borrowing brings us to the album's cultural friction. Puente was always gracious about Santana's cover, but the undertones of ownership and origin run through any serious listen of ÒEl Rey.Ó This album reasserts authorship. At a time when Latin music's textures were being lifted into other genres without always being credited, Puente offers a reminder: this sound has lineage, has names, has meaning. And it was born not in a boardroom, but in barrios and ballrooms.

Echoes in Modern Music

You don't have to squint too hard to find ÒEl ReyÓ in today's grooves. Listen to Marc Anthony's precision phrasing, Ozomatli's percussive urgency, or even Thundercat's jazz-infused basslines, and you'll hear ripples from Puente's tide. And while the album may not be the most commercially known in his catalog, it stands as one of his most musically assertiveÑa field manual for percussionists, arrangers, and anyone who ever dared to put swing into syncopation.

-HOMENAJE-A-RAFAEL-HERNANDEZ-400med.jpg)