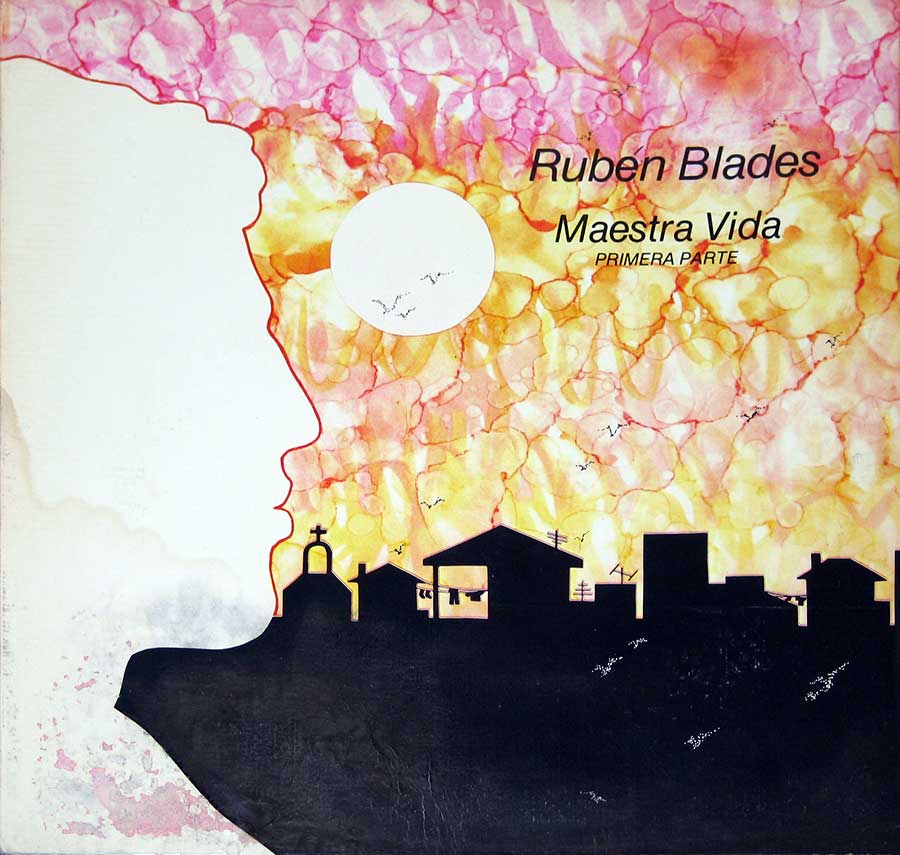

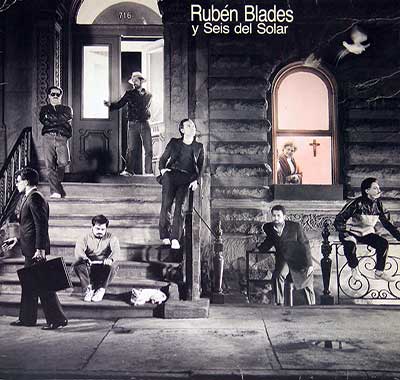

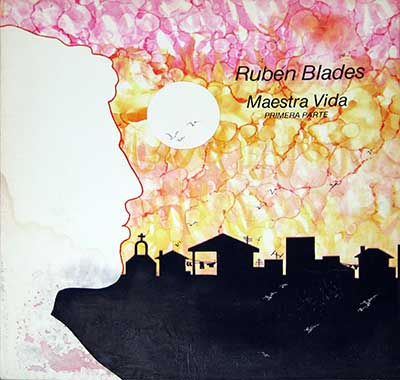

RubŽn BladesÕ First Salsa Opera Steps Onto the Stage (1980) Album Description:

By 1980, New York salsa had outgrown its bar-band adolescence. RubŽn BladesÑlaw student by day, streetwise sonero by nightÑanswered the moment with ÒMaestra Vida: Primera ParteÓ, a narrative song-cycle that treats the barrio like a theater set. The record doesnÕt just collect tunes; it frames characters, conflict, and consequence, and asks salsa to carry a story the way Broadway carries oneÑonly with clave as the pit conductor.

Historical Context: FaniaÕs New York and a New Lyrical Temperature

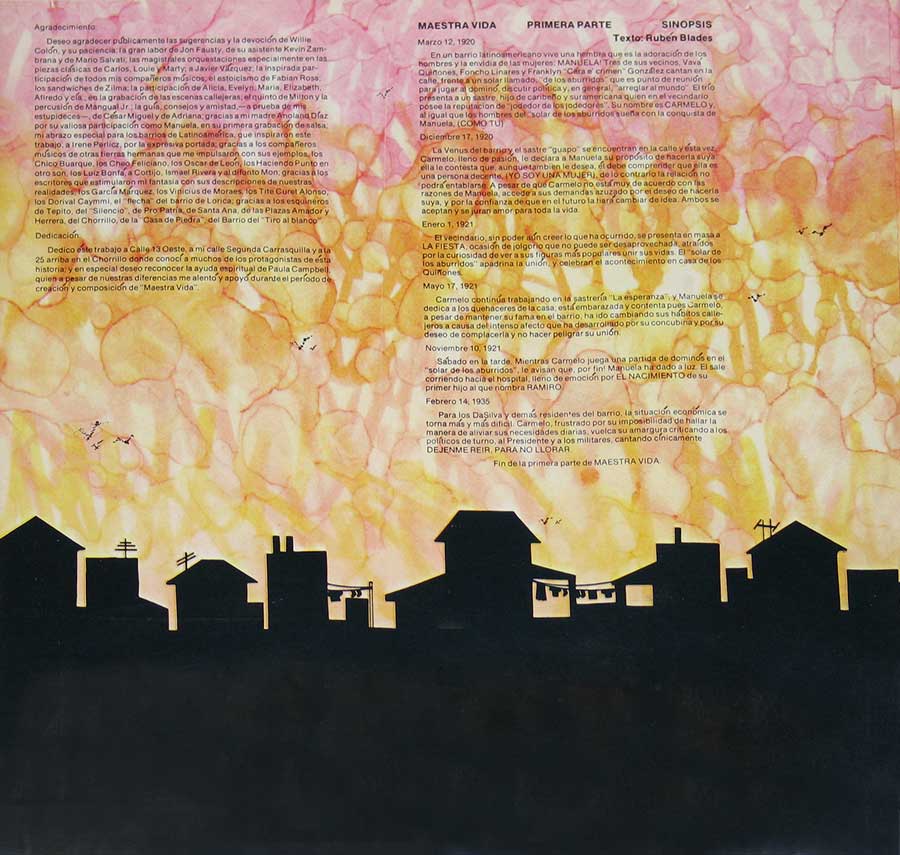

Blades arrived at this project after the seismic jolt of ÒSiembraÓ (1978) with Willie Col—n, the LP that proved social narrative could dance and still sell. Fania, the label that turned Spanish Harlem into a global signal tower for salsa, was at full wattageÑand full friction. The scene fostered big bands and bigger ambitions, and Blades, steeped in nueva canci—nÕs penmanship, set out to write cinema for the dance floor.

Concept & Musical Exploration

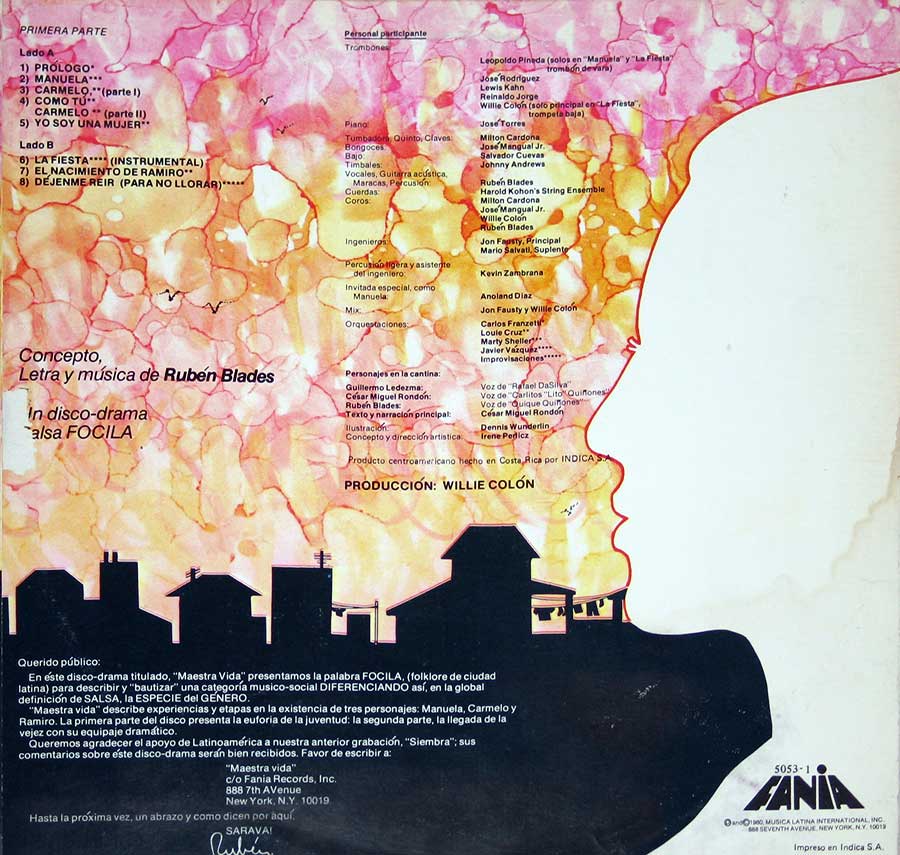

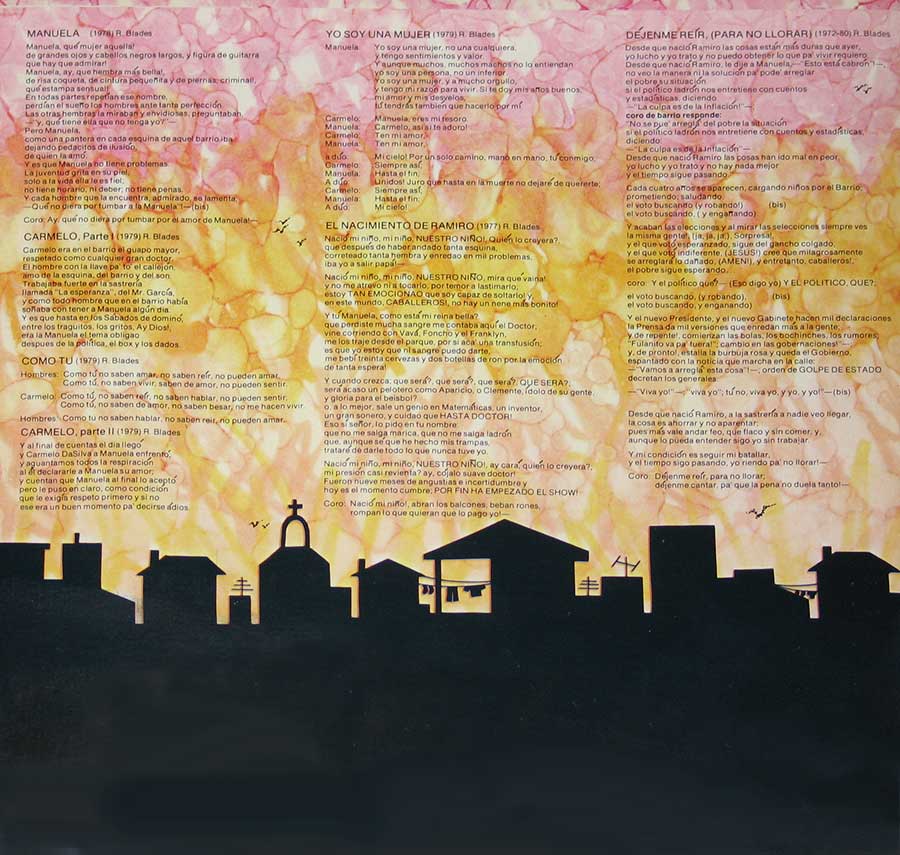

ÒMaestra VidaÓ deconstructs the late-Õ70s salsa formula. Willie Col—nÕs production splices classical motifs, woodwinds, and brass into Afro-Caribbean meters, while excursions through samba, bossa, plena, bomba, and dŽcimas widen the canvas without snapping the claveÕs backbone. The narrative tracks the tailor Carmelo, his partner Manuela, and their son RamiroÑfrom prologue through birth to economic squeezeÑso that each rhythm colors the plot, not just the groove.

Key moments: the radio-trimmed hit ÒManuela,Ó presented here in its full dramatic arc; ÒYo Soy Una Mujer,Ó voiced with flinty dignity by BladesÕs mother, Anoland D’az; and the closer ÒDŽjenme Re’r (Para No Llorar),Ó a bomba-to-plena pivot that ridicules small-town political hypocrisy while CarmeloÕs frustration boils over. ItÕs storytelling with a dance card, equal parts stagecraft and street chronicle.

Players in the Pit: Musicians Who Make the Story Swing

The albumÕs authority comes from identifiable voices in the instrumentation. Trombonist Leopoldo Pineda steps out with a muscular solo in ÒManuela,Ó a line of brass that sounds like a character entrance. Electric bassist Sal Cuevas lays down the elastic, percussive foundation that keeps the suite moving scene to scene. The coro of Milton Cardona and JosŽ Mangual Jr., alongside Col—n and Blades, brands the record with that gritty New York blend of harmony and chant. Arrangers across the sessionsÑCarlos Franzetti, Louie Cruz, Marty Sheller, and Javier V‡zquezÑshape the orchestral swirl around the narrative spine.

Band History in the Frame

Place this LP in the Blades/Col—n timeline and it reads like a hinge. Before it came the commercial and cultural thunder of ÒSiembra.Ó After it, the partnership would deliver more studio chapters before diverging: Blades soon steered toward projects that sharpened his authorial voice, eventually fronting his own ensembles. In 1980, though, the band still bore Col—nÕs trombone authority and BladesÕs narrative urgencyÑan alliance poised between the dancehall and the dramaturgÕs desk.

Controversies: Art, Labor, and the Business of Salsa

The album also lives in the shadow of industry conflict. Around this period Blades clashed with label brass over royalties and helped agitate for musicians to organizeÑmoves that reportedly drew retaliation from executives, even as allies like Col—n and Cheo Feliciano stood close. The tension between art and commerce is part of the recordÕs grain; you can hear the urgency of a writer who knows the stakes extend beyond a dance floor.

Years later, strains within the Blades-Col—n orbit surfaced in court filings tied to performance-fee disputes, a reminder that the eraÕs creative glories were chased by hard business weather. While those legal battles sit outside the albumÕs narrative, they color the partnershipÕs historical backdrop and the working conditions around salsa at the time.

What the Record Sounds Like in the Room

Think of ÒPrimera ParteÓ as a small theater with great acoustics: strings and French horns usher you to your seat; a percussion battery places you at a corner table where the story unfolds; trombones argue and affirm; the coro acts like a Greek chorus from El Barrio. BladesÕs phrasingÑequal parts poet, reporter, and soneroÑthreads the scenes until politics and romance share the same dance step.

Why It Matters Inside 1980

Without leaning on its later reputation, the significance in the year of release is clear: this is salsa proving it can carry theater-grade narrative weight without forfeiting swing. It captures a New York Latin community arguing with itself about power and possibilityÑand sets a literary bar for the genre that many would measure against thereafter. In that sense, ÒMaestra Vida: Primera ParteÓ is less an album than an evening at the playhouse, with the band in the orchestra pit and the neighborhood onstage.

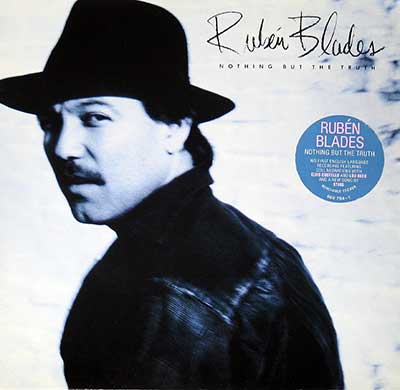

About RubŽn Blades

"Rubén Blades Bellido de Luna" is a Panamanian salsa singer, songwriter, lawyer, actor, Latin jazz musician, and politician, performing musically most often in the Afro-Cuban and Latin jazz genres. As songwriter, Ruben Blades brought the lyrical sophistication of Central American nueva canción and Cuban nueva trova as well as experimental tempos and political inspired Nuyorican salsa to his music, creating thinking persons' (salsa) dance music. Ruben Blades has composed dozens of musical hits, the most famous of which is "Pedro Navaja," a song about a neighborhood thug who appears to die during a robbery (his song "Sorpresas" continues the story), inspired by "Mack the Knife." He also composed and sings what many Panamanians consider their second national anthem. The song is titled "Patria" (Fatherland).