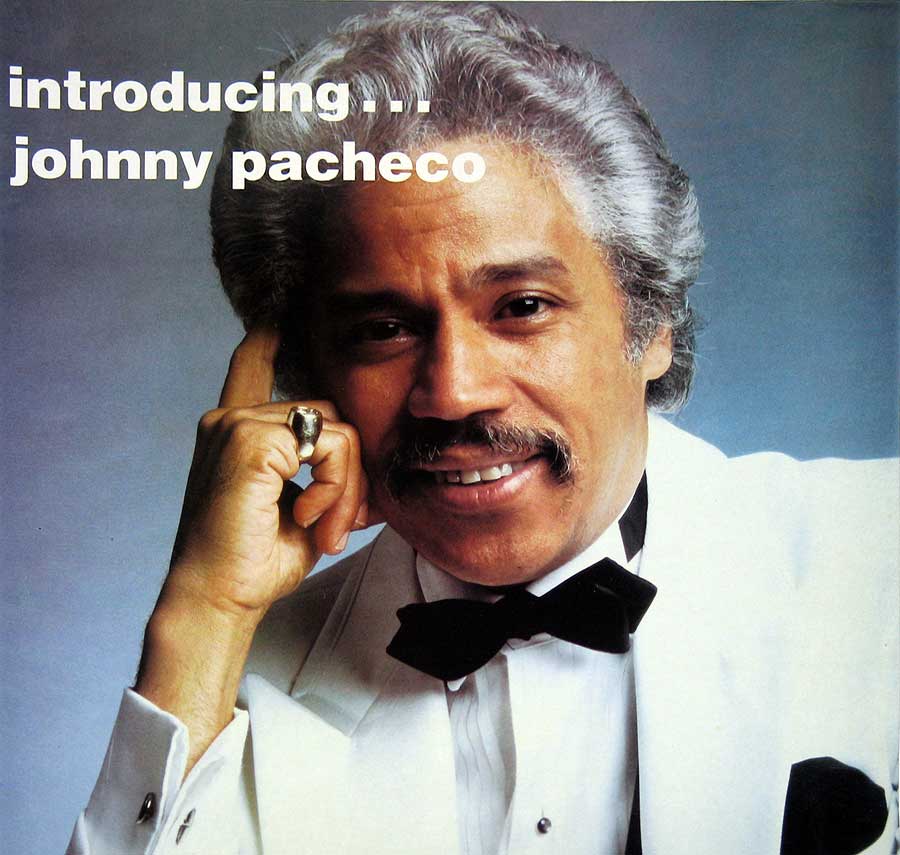

"Introducing Johnny Pacheco" (1989) Album Description:

I’ve got a soft spot for compilations that don’t act polite and call it “curation.” "Introducing Johnny Pacheco" hits like someone shoved the doors open and let the whole room spill out: flute riding high, percussion snapping underneath, and not a second wasted trying to charm you into listening. It’s 1989, it’s Caliente HOT 121, and the record doesn’t ask permission before it starts moving.

1989 in the air: shine on the surface, sweat underneath

Late ’80s Latin releases could come dressed up—clean fonts, cleaner edges, romance drifting into places that used to be all elbows and percussion. Fine. People fall in love, the radio wants hooks, the world keeps turning. But a Pacheco set like this still feels built for rooms with bodies in them, not for polite listening at half volume while someone explains “cultural importance” over cheese cubes.

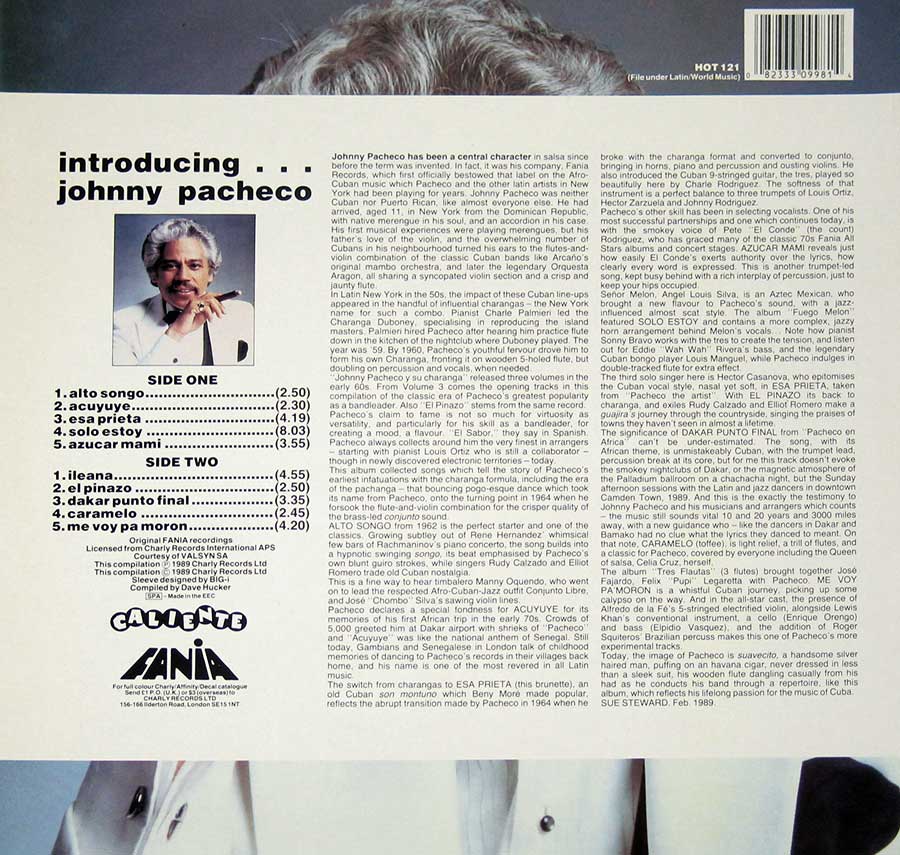

This particular issue—UK, Caliente imprint, Charly sound copyright floating around the label copy—smells like that Charly-world approach: grab the right material, line it up so it plays like a proper night, and get it out where people can actually buy it. Not glamorous. Effective. Sometimes that’s the whole job.

Genre context: where this sits when the salsa aisle gets crowded

Put this next to the heavy talkers and the architects and you hear what Pacheco does differently. Willie Colón and Rubén Blades could turn a tune into a street argument. Eddie Palmieri builds rhythm like scaffolding. Tito Puente comes in with that brass-and-timbales authority. Celia Cruz can light a whole block with one shout.

Pacheco? He drives. The flute isn’t decoration—it’s a steering wheel. He keeps the band pointed forward, even when the rhythm section is trying to drag the car sideways.

- Against late-’80s smoothness: this stays sharper, more bandstand than bedroom.

- Against the grand statement makers: less speech, more motion.

- Against the jazz-leaning experiments: the brain stays employed, but the hips get the paycheck.

The sound: flute that cuts, percussion that argues back

The flute tone here isn’t the polite conservatory thing. It’s bright, quick, a little cocky—like it knows it can slice through horns and still land on its feet. Under it, the groove doesn’t “support” anything. It pushes. It shoves. It keeps poking you in the ribs until you stop standing there like a statue.

The tempos feel dancer-first: not rushed, not lazy—just that relentless forward roll where the pocket keeps tightening, then loosening, then tightening again. You can hear the band breathe together, the way good rhythm sections do when they’re watching the floor instead of worshipping the click track.

Track-listing, but as nightlife

Side One comes out swinging: "Alto Songo" opens the door, "Acuyuye" slips through the crowd, "Esa Prieta" keeps the room honest. Then "Solo Estoy" stretches out—longer, moodier, the kind of track that lets the band lean back and still keep the tension humming. "Azucar Mami" sweet-talks for about half a second, then gets right back to work.

Side Two doesn’t drift. "Ileana" brings a broader breath, then "El Pinazo" snaps you back into the tighter frame. "Dakar Punto Final" and "Caramelo" feel like the moment the band realizes the room’s still with them and decides to press harder. "Me Voy Pa Moron" closes like a last grin on the way out—no bow, no thanks-for-coming speech.

Key people: what they practically contributed

Johnny Pacheco—Dominican-born, New York-shaped, the kind of bandleader who doesn’t need to shout to make the band obey—runs this thing with arranger instincts and a performer’s timing. His playing isn’t floating above the rhythm; it’s leaning into it, pulling it, daring it to keep up.

The only named credit you’ve got on the page is Dave Hucker tied to Charly Records, and the safest, most honest way to frame that is this: he’s the hands-on “put it together” guy. Selection. Ordering. Notes. The unsexy work that makes a compilation feel like a set instead of a random bag of tracks dumped on your lap.

Band events, minus the boring timeline

Trying to talk about Pacheco like he’s a fixed rock lineup misses the point. His world is charanga and salsa culture—players rotate, singers rotate, the scene shifts, the rooms change. Cause and effect isn’t “so-and-so quit.” It’s “the dance changed, so the band changed,” and the leader who survives is the one who can keep the music tight without freezing it in place.

Controversy: nothing dramatic, just the usual bad assumptions

No big public scandal hangs off this release—no famous ban, no tabloid fight worth framing on the wall. The real problem is smaller and more annoying: people treat compilations like they’re biographies. Ten tracks do not explain a life. They open a door. Whether you walk through it is your problem.

Another dumb assumption: flute-led salsa must be “lighter.” Put this on loud. Listen to the percussion argue with your heartbeat. Then tell me it’s light with a straight face.

One quiet personal anchor

I can see this record in a scuffed “LATIN” bin with a hand-written price tag, filed under “P” because somebody couldn’t be bothered with first names. You take it home, drop the needle, and your living room immediately starts acting like it paid a cover charge.