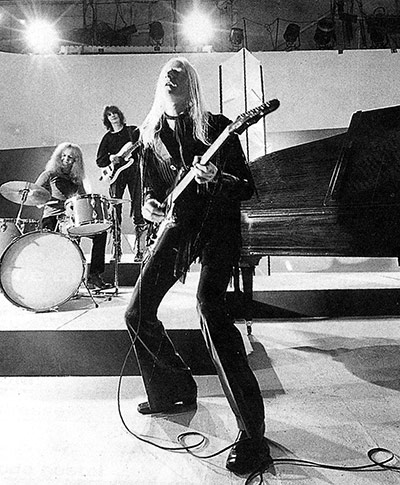

By Jon Millingtowne

'He's a skinny, long-haired, white-haired, pale, blues-living guitarist from Texas. I don't know if Winter is the name he was born with but it's certainly his real name. His incredibly white skin and white hair remind us of the icy season. The word Winter reminds us that if he were in a movie he would play the part of Death. But the truth is he's not in any kind of movie. And he makes music. He makes life. In the days we know little about, the days when history was sung rather than written, those who gave life were called heroes and kings. Ultimately they were called gods. The ritual elevation to gudhood was called apotheosis.

Now, when strangers are brought together at early morning hours by the whimsey of bus depots they still recount the story of how Johnny Winter came to be known. They talk knowingly of the article that appeared in Rolling Stone — the article that told of the Texas music scene in general. It mentioned Johnny Winter in particular. It indicated that he was magnificent beyond the limits of mortality. And then the words Steve Paul are uttered. They tell of how Steve Paul walked out of his New York night club. The Scene. hailed an aeroplane and flew to Texas to find Johnny Winter and bring him to New York to make music and add more life to his scene.

They tell each other of how Steve Paul became Johnny Winter's manager. The record companies fought for the right to record Winter. He and his grout. ultimately signed with Columbia Records. He appeared at the Filmores East and West. rehearsed in rural New York State area and eventually made prestigious public appearances making a lot of friends and money. Buses come into the depot to bear the spreaders of legend to distant parts of the land. There is momentary silence. A dime falls into the juke box (click) and the telling of the legend begins again. Johnny Winter tells a variation of the story. He tells of how he learned to feel blues and how he became unknown and how he was discovered and how he is now.

"I never really felt strange about going Into the black clubs and being in there if the people didn't feel strange about having me in there. In most cases they didn't seem to. There was never one incident. Maybe somebody would say something. There was never any real incidents. Maybe, once in a while. a black chick would ask me to dance just because she'd think, 'well this white cat coming in here. I wonder if he really likes us.' I'd be there listening to the music and not really wanting to dance anyway. If she were a white chick I wouldn't want to dance because I only wanted to hear the music. But instead I'd feel obligated.

That's the only kind of incident that would come up." But Johnny did have some problems with the owners of the clubs he worked in. 'These people had the P.A. control behind the bar sometimes and they would turn it up loud as they wanted. If they thought the band was too loud they'd turn the vocal down so you'd have to play quieter. I'd walk off the bandstand and do horrible things. I also knew club owners who would pick records off the radio and say 'you've got to learn this one next week.' And I did. You had to do it or starve. It was either do that or work in a filling station. "But the way things were going the other guys in the band had it worse than I did. Because I lived with a chick that was working regularly.

She didn't make a lot of money but she made 575-100 a week and I made money and I had a little money that I saved up that I had in the bank from when I was doing well. "We had an old Packard hearse, an old '52 Packard hearse that we have to get fixed up again. It's in Austin. It's a great car. People really, really, really couldn't believe us driving this big old hearse around Texas. Most of our money just went into keeping the car rolling, gas and other things, but it really wasn't as bad for me as it was for those two guys. That's why I hate to see them getting all the criticism. Like people ignore the fact that we're even a band. It's like Johnny Winter.

"At the start, the name of the band was Winter and it was a complete thing we were doing together. Now people are saying, 'Johnny Winter and the two shitty guys that are hanging on.' That's not right because the sacrificed even more than I did. They hadn't been into blues as long as I had. "As soon as I turned them onto blues they got excited and began to learn. I'd play records for them and they were getting into it, too. I played everything I had for them like a lot of Muddy Waters' things, Robert Johnson, Little Walter and just samples of B.B. King.

I'd say 'this is a good example of Chicago Blues and this is a good example of Delta Blues'." Every once in a while. Johnny ventured forth from Texas to seek his fortune. "I'd gone to England once and I was going to go back to England and work over there recording and working over in England. There was a local company that was offering several thousand dollars for me to sign with them, like five or six thousand dollars. At the time, we had nothing. You know like from nothing to have somebody say here's five thousand dollars. Finally it got up to where it was going to be like 10. maybe 15, I can't remember exactly.

"But they'd say things like. 'Well, you can have all the control over the tunes but we can't put that into the contract because what if you get in there and you just go crazy. We've got to have some controls and it's just got to be that way.' And I didn't want that. I knew exactly what I wanted because I've been screwed so many times. These people figure 'you're a musician, man. but I know people and I know what's going to sell. I know what people will pay money to hear so you should do it my way. You're the musician and I'm the business guy so I know better. I thought that I knew better and I didn't even care if I didn't know better.

I still wanted to do it my way. "I've been screwed a bunch of times. Everybody I ever recorded for said 'Listen to this record by Bobby Darin. Listen to how the drums go. And listen, man, this one sells a lot of records. Copy this and write your own words to it and it'll probably be a hit because so-and-so did it last week and this is real big on the charts and this is the sound that's happening now' and all that stuff that, you know, I hated. And I dedicated myself to never doing that again. And I was very wary of it. I just wasn't going to have a manager.I already turned down a lot of things because people would do that.

And I didn't think I'd have a chance to do things exactly the way I wanted." So. back to Texas and back to everything as it was. until that Rolling Stone appeared. And then Steve Paul appeared. "I thought he was a nut. I thought he was crazy. Down there all the people act like him. Steve's a big hype person all the way. He comes on that way. The big hard sell. You gotta come to New York play at my club and well do all this for you' — and the people who ran things down there were short-haired, older people and the people like Steve screwed up. I didn't know what was true. I'd heard of the Scene. I heard of Steve Paul and I really was at the point where I really didn't think he was real.

"I thought he was lust some nut who had read the article and told me he was Steve Paul. I really didn't believe him. I was already supposed to go to San Francisco and I had already promised to go there and work the Matrix and Steve would say 'you've got to come to New York now. First.' And I told him I can't do that. I'll come to New York later. I planned on going. I figured I didn't care how much of a nut he was. If he's going to give me a free plane ticket. I'd go for that. "Hut when I got to San Francisco. he'd call me at places where I had no idea he could find out where I was. I would be eating somewhere and get a call from Steve Paul. And he'd give me the same stuff.

'You got to come to New York. right now, man. It's very important because this week there's going to be a lot of people at the Scene because Hendrix is there and you can jam with him and it's really important that you go right now.' " "I said leave me alone. man. I'll come when I can. He'd bug me every day and talk for an hour on things that I didn't care about. He was telling me the same things over and over. 'You got to get up here. You got to get up here.' I told him I was coming later when I could. I went back to Texas and things worked out so that I could come and I figured I'd go there and see what he could do.

"I didn't really want a manager because I wanted to do everything myself. I figured I'd go up there and chock It out and at least get him off my back so I could say I've been there. And as soon as I wont there. just immediately. I realized that he would do what he said and another thing that I thought he would do that I really didn't want him to do Was try to tell me what to do, how to play and if you wear a red shirt they're going to like you better. and how to commercialize and how to set up for the kids. And he didn't do that at all. He didn't try to make me do these things. Everything he did was natural. If I didn't like it. he'd leave me alone. If I said 'I don't like this it isn't really me.' he'd immediately quit.

"Right away in the first two or three days I knew it would work great. Like, in San Fran-cisco. people liked me just as much as they did in New York. But yet I didn't get any press. Nobody was there. When I was with Steve he took me to Fillmore.' lammed. He did business type things like making sure the photographers were there, making sure the press was there. making sure the right people were there to hear me which is not hype. It's lust good business you know. Well. It's hype in a way but it's not dis-honest. "Hell. I've been playing for ten years and nobody would even listen to me. You got to do someting. You can't sit there hoping.

You got to go out and force them to hoar you. If they like, it. okay. If they don't. "He didn't bother me. He didn't mess with my music at all. We work together real well. And I think he was everything he seemed to be and It's been greet. We have a good re-lationship." And even before the news that Columbia Records paid somewhere between $300,000 and $600.000 the journalists of the land paid court to Johnny Winter. "I've been wanting to say things for ten years and I haven't had a chance to. You know it's great, man. It's not a drag for me at all. It's great that I have people who want to listen, just things like this kind of talking is great for me.

After ten years of talking and having everybody think you're crazy." When the record was made. one of the musicians who augmented the basic trio was Edgar Winter. Johnny's brother. "Edgar is an excellent musician. He's much better than I am technically but we're into such different things. Blues is not commercial and all. but it lust happens that what he's doing is also not commercial. I don't really know what he wants to do. He's never had a chance to do what he wanted. "I'd like to give him a chance to do the same thing that I did. lust have him come up and not have to play with me. Thai would be horrible to have him play stuff that he doesn't want to play.

It would be great if I could help him get musicians that he really enjoys playing with. I think I can because of the whole big deal—albino freak making it—and here's another one so everybody in the record business can't wait to pick up on it. 'That's one thing that almost pisses me off. I was never bitter about the fact that I was different that I had a hard time 1 never felt like 'poor me. why did this happen and all that stuff.' It never really bothered me. And now there have been several things written about me—The world is ready for any freak. any freak can make it' — just because I'm albino and look strange. Now it's supposed to be such a great and wonderful thing.

The magic in the music doesn't really make any difference. "lust because I'm weird people are ready to pick up on it. And for so many years. I didn't make it. especially in the old days of all the teenie hopper regular good looking beach boys. Can you imagine me in that bag. I didn't mind putting up with it all those years. How can people say it's an advantage now and I'm making it now because of that. It's a disadvantage again because people think that's the reason I'm here and that's the reason instead of appreciating the Music. "I'd hate to make it like that because I don't see myself as a Tiny Tim person that's just putting on a show or are there lust be. cause I am a freak.

It's just something that's there. Like some people are black. I want people to like me for my music and for what I do and lust dig that more than anything else. "I consider what I do just talking to people just a conversation. I can't perform. One thing I'm really horrible at and can't do is perform. is act. Like when you walk out there with a big smile and say 'hi there.' It used to be the big thing in the clubs where you are supposed to make everyone happy and keep them drinking. You know. 'water up folks. Last call for alcohol.' I can't do that. If I'm hating something I act like it. If I'm happy. I'll jump around and scream and do all kinds of things.

I can't put it on. It's impossible for me. I just can't. "Whenever I've tried to do it it seemed to me so ridiculous. I know people say the music business changes you. It can't change me. I know what I could do. I play guitar good. I sing good and I do good blues." Two strangers share a table in a night-time neon cafeteria. The coffee steams into the vacuums of their mouths and then words tumble out. Words about life-giving dynamite blues man Johnny Winter. And In the pleasure of these words are the simple truths upon which legends are built:

He plays guitar good; he sings good; and he does good