Bob Geldof: A Comprehensive Biography

Early life in Ireland: grief, grit, and a front-row seat to a changing country

Bob Geldof was born 5 October 1951 in Dún Laoghaire, near Dublin—an Ireland that still felt small, watchful, and tightly buttoned-up, even as the modern world kept knocking on the door. Losing his mother when he was a kid didn’t give him a “tragic backstory” so much as it gave him a sharper edge and a radar for unfairness. School, odd jobs, and that constant Irish hum of “don’t get notions” all shaped him into someone who’d eventually get very loud about not staying quiet.

Before the microphone: the journalist phase and the outsider’s eye

Before he became the guy yelling into the cultural weather, he worked as a music journalist in Vancouver for The Georgia Straight. That matters, because it trained him to watch scenes like a hawk: who’s faking it, who’s starving, who’s being ignored, and who’s about to explode. He didn’t just want to be in a band—he wanted to say something, and saying something is easier when you’ve spent time documenting other people’s noise first.

The Boomtown Rats: Dublin attitude meets London punk-era oxygen

The Boomtown Rats formed in 1975 in Dublin, then did what ambitious bands did in that era: they went where the industry actually was—London—and tried to survive. The late ’70s were basically a cultural bar fight: punk had cracked the old rules, new wave was turning rage into hooks, and pop was learning how to be sharp again. Geldof fit right into that chaos, because he could sound theatrical and furious in the same breath, like he was reporting live from the inside of the song.

Breakthrough hits: turning social bite into chart power

The Rats didn’t just flirt with success—they landed real punches. “Rat Trap” hit No. 1 in the UK in 1978, with Bob Geldof writing it and Robert John “Mutt” Lange producing it—yes, that Mutt Lange, the guy who knew how to make rock sound huge without sanding off the teeth. It mattered culturally because it was an Irish band muscling into the UK charts during an era when rock was being rewritten in real time.

“I Don’t Like Mondays”: when a pop song walks straight into controversy

Then came “I Don’t Like Mondays”—a massive hit, and also a lightning rod. The song was inspired by the 1979 Cleveland Elementary School shooting in San Diego, after the shooter’s chilling quote got repeated in the news like the world’s worst catchphrase. Musically it’s polished new wave-pop; emotionally it’s a cold stare. It was recorded at Trident Studios in London and produced by Phil Wainman, and it raised the obvious debate: should a chart single go anywhere near real tragedy—or is that exactly what art is supposed to do when reality gets unbearable?

Acting detour: stepping into Pink Floyd’s nightmare

In 1982, Geldof starred as Pink in Pink Floyd – The Wall, directed by Alan Parker and written by Roger Waters. It’s not a cute cameo; it’s a full-body plunge into a bleak, surreal story about fame, isolation, and psychological collapse. If you ever wondered whether Geldof could project “tired of the circus” without saying a word—yeah, he could.

Why the mid-’80s mattered: pop stardom meets global emergency

By the early to mid-’80s, pop had become truly global—satellite TV, mass broadcasting, superstar branding—while politics and humanitarian crises were landing in living rooms with brutal clarity. The 1983–1985 Ethiopian famine hit Western screens in a way that bypassed polite distance, especially after BBC reporting shook the public. This is where Geldof’s story swerves: instead of just writing another angry song, he tried to weaponize celebrity attention for actual money and actual logistics.

Band Aid: one day in the studio, a cultural shockwave

In 1984, Geldof and Midge Ure pulled together Band Aid and co-wrote “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” to raise funds for famine relief. The track was recorded at Sarm West Studios in Notting Hill, London in late November 1984, produced by Midge Ure, and released in early December. The concept was simple and kind of audacious: trap the entire pop ecosystem in a room, remove the usual ego choreography, and press “record” before anyone can overthink it.

Live Aid: the day the planet watched the same show

Live Aid followed on 13 July 1985, staged simultaneously at Wembley Stadium in London and John F. Kennedy Stadium in Philadelphia. Geldof and Ure didn’t just “host a concert”—they engineered a media moment that made charity look urgent, mainstream, and unavoidable. It became a blueprint for how benefit events could work at scale: broadcast-first, globally coordinated, and emotionally direct enough that you couldn’t just shrug and change the channel.

Sport Aid: when the benefit format left the stage and hit the streets

In 1986, the idea expanded again with Sport Aid, which culminated in the Race Against Time, a 10K run held simultaneously across dozens of countries. It wasn’t only about star power; it was about mass participation—millions of ordinary people turning movement into fundraising. Geldof was among the organizers alongside partners linked with UNICEF, which shows how his activism was shifting from “rock star initiative” into bigger institutional territory.

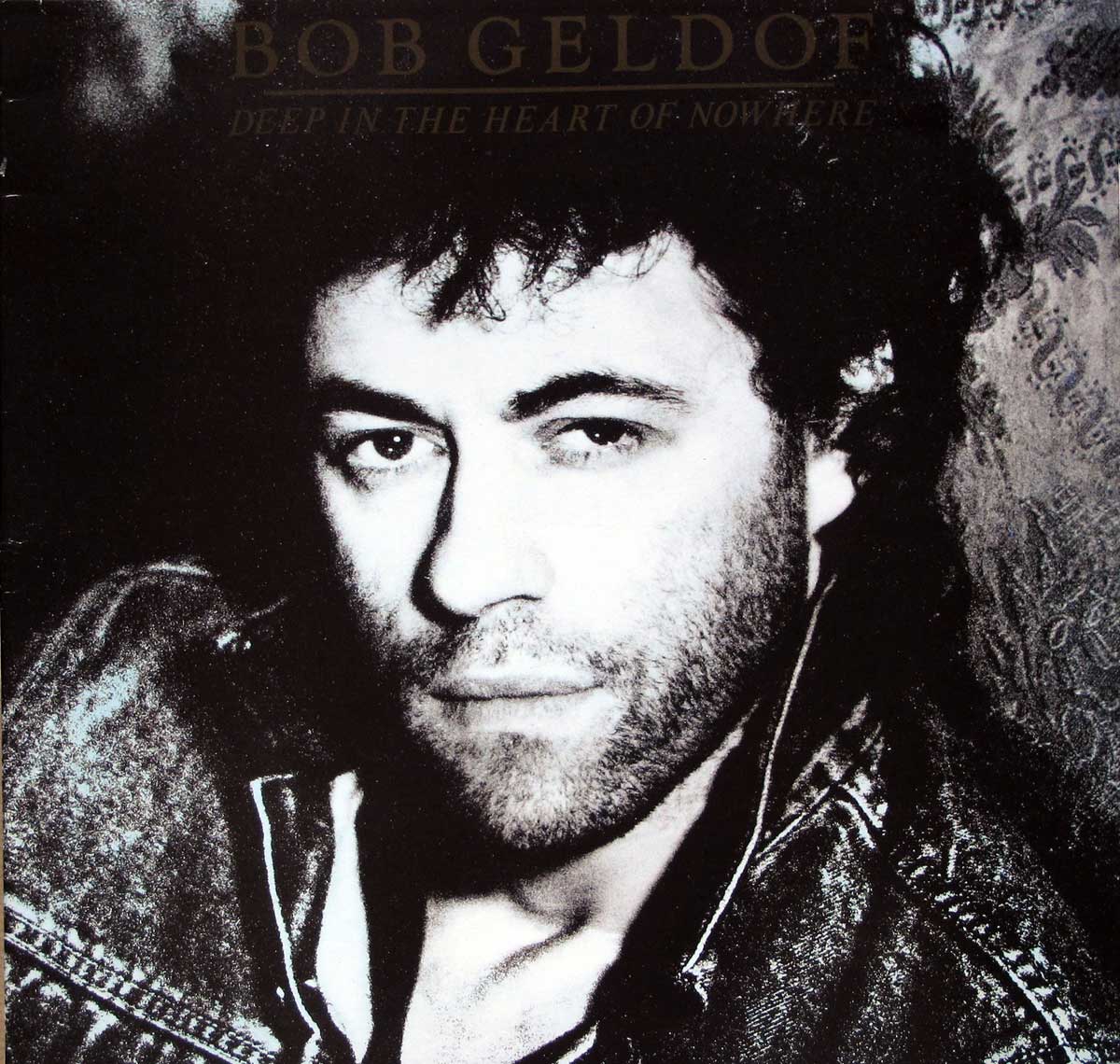

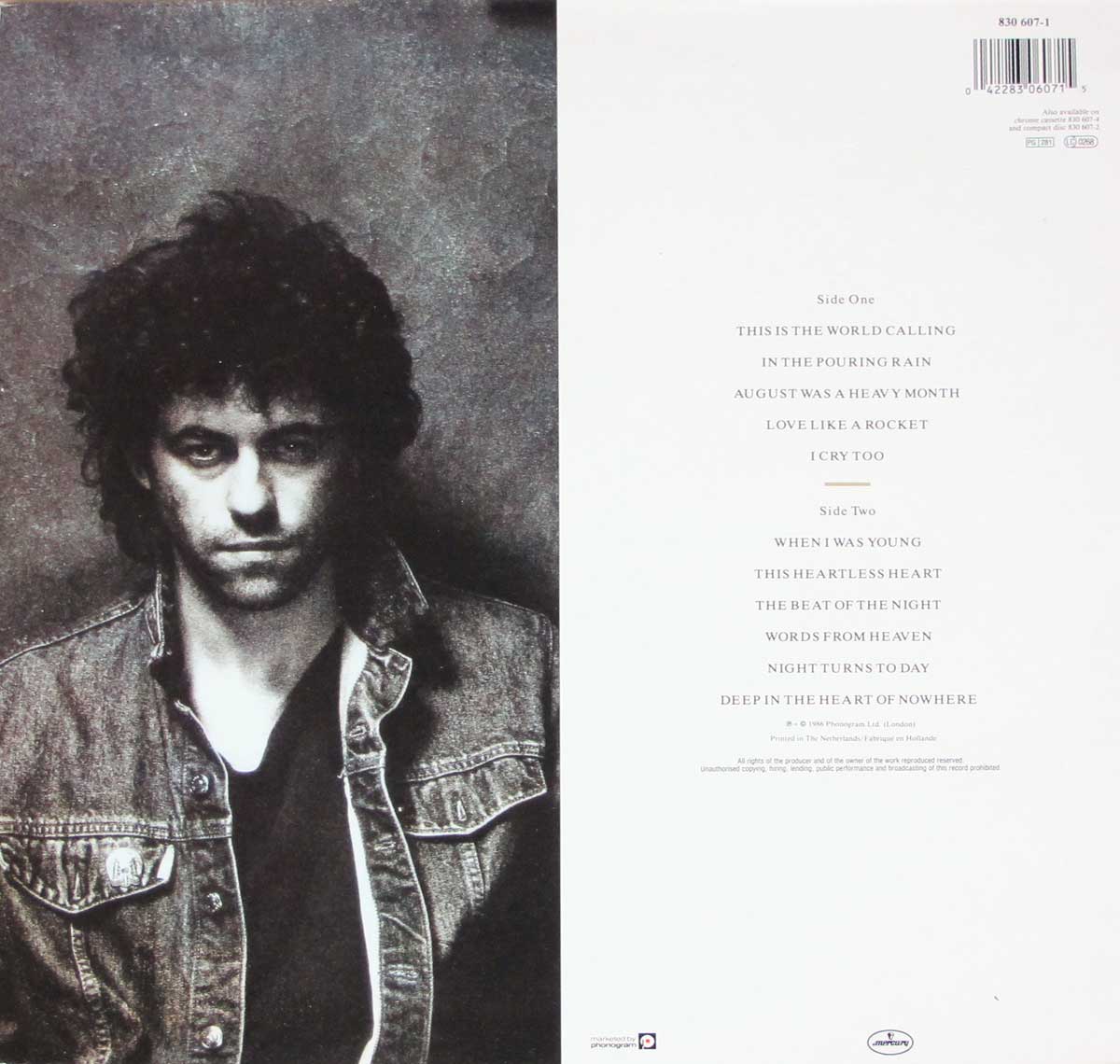

Solo career pivot: stepping out of the band identity

In late 1986, Geldof released his first solo studio album, Deep in the Heart of Nowhere, on Mercury, produced by Rupert Hine. The timing is telling: post-Live Aid fame could’ve turned him into a permanent spokesperson, but he still insisted on being a working songwriter. In my head, this is the era where he sounds like a man trying to balance two lives—artist and agitator—without tearing in half.

The people behind the sound: producers, engineers, studios, and the “invisible band”

If you want the connective tissue across his career, follow the production fingerprints. You’ve got Mutt Lange producing “Rat Trap”—tight, punchy, radio-ready rebellion. You’ve got Phil Wainman producing “I Don’t Like Mondays” and the recording tied to Trident Studios in London—a classic studio name that screams “real deal” era. Then you’ve got the charity end: “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” cut at Sarm West Studios with Midge Ure producing—proof that a studio can become a temporary command center when the mission is bigger than the music.

Controversies: art, activism, and the price of being loudly certain

Geldof’s controversies mostly come from the same engine that powers his best moments: blunt urgency. “I Don’t Like Mondays” got pushback because it turns a real atrocity into a pop narrative, and some listeners will always find that line uncomfortable—fair. On the activism side, “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” and the broader Band Aid/Live Aid era has been criticized for oversimplifying Africa, leaning into stereotypes, and giving off “white savior” vibes even when the intent was genuine. The hard truth is that global charity is never a clean story, and Geldof has never pretended he’s a soft-spoken diplomat about it.

Live 8: pressure politics, not just relief money

In 2005, Geldof and Ure returned with Live 8, a series of concerts timed right before the G8 summit at Gleneagles. The point wasn’t only fundraising; it was political pressure—debt relief, aid commitments, trade issues, the whole messy policy buffet. Live 8 showed how his activism had evolved: less “emergency response,” more “systemic argument,” delivered through the loudest megaphone pop culture can build.

Honours and recognition: the weird moment when the establishment applauds the troublemaker

In 1986, he received an honorary KBE (KBE stands for Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire) for his charity work—an Irishman getting a British honour, which is historically… loaded, to put it politely. It’s one of those moments where the system basically says, “We don’t know what to do with you, so here’s a medal—please don’t bite.” Of course, people still call him “Sir Bob,” even though it’s honorary, because the internet loves a shortcut almost as much as it loves an argument.

The through-line: a songwriter who refuses to stay in one box

When I map Bob Geldof as a whole, I don’t see a neat “musician” lane and a separate “activist” lane—I see one person with a permanently switched-on sense of outrage, using whatever platform is available. Sometimes that platform is a three-minute single, sometimes it’s a global broadcast, sometimes it’s an argument with the world about how charity should look. The vibe is consistent: restless, direct, and allergic to doing nothing just because doing something is complicated.