People love to retell Anvil’s origin story like it’s a neat little timeline. It wasn’t. Steve “Lips” Kudlow and Robb Reiner were already making noise together around 1973, bouncing through early band names (you’ll sometimes see “Gravestone” attached to that pre-history), but the actual band that matters starts in Toronto in 1978: Lips. Same two guys at the center, plus Dave “Squirrely” Allison on guitar and Ian “Dix” Dickson on bass. Four friends, one shared volume problem.

LIPS (Steve Barry Kudlow) didn’t “become” Lips like it was a brand decision. He leaned into it. You can hear the intent in the way the songs move: not polite, not careful, more like “turn it up and see who flinches.” In 1981 they put out Hard ’n’ Heavy on their own under the Lips name, then—after getting picked up by Attic—switched the band name to Anvil and re-issued the album as their debut. Some folks call that a rename. I call it a survival tactic… and a small act of stubborn pride.

ANVIL started in Toronto in 1978, and the funny part is how “unfunny” the commitment is. Steve "Lips" Kudlow and drummer Robb Reiner didn’t build a legend so much as they kept showing up—again, and again, and again—like the door to the rehearsal room was the only door that ever made sense. That’s the core of it: not fame, not myth, just stubborn motion.

People call them “pioneers,” which is a little too clean. They weren’t inventing metal in a lab coat. They were plugging into the same dark electricity as Black Sabbath, Judas Priest, and Motörhead—then pushing it forward with a speed-and-grit attitude that later bands openly credit. When I think of early Anvil, I don’t think “historical importance.” I think: cheap amps, bright cymbals, and songs that swing a hammer instead of politely making a point.

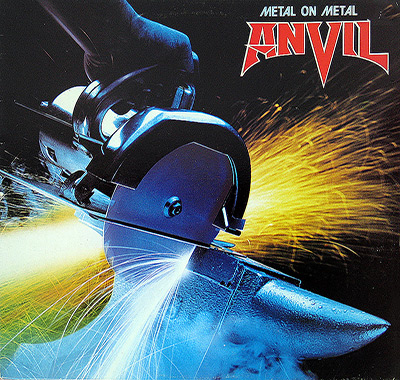

If you want the receipts, start with "Metal on Metal" (1982) and "Forged in Fire" (1983)—records that don’t ask permission. And yes, the story includes the rough years: day jobs, small rooms, the kind of touring that looks glamorous only to people who’ve never slept sitting upright. The 2008 documentary didn’t magically “fix” anything, but it did shove them back into the light for a while—long enough to remind everyone they were still here, still loud, still refusing to behave.

The DIY thing is real—just not in the mythy “they did everything themselves forever” way. Anvil are hands-on because they have to be. They write, they grind, they keep the machine moving, even when the industry would rather you quietly disappear. That’s not a brand strategy. That’s survival with a backbeat.

Anvil’s “longevity” isn’t some inspirational poster. It’s miles. It’s repetition. It’s the same ritual played out in different rooms: load-in, soundcheck, the quick scan of the crowd to see who showed up on a weeknight, then that moment when Robb counts it off like the rent depends on it (because sometimes it does). I’ve seen bands save their energy for a bigger night. Anvil don’t really do that. Even in a small club, they hit like they’re trying to knock the paint off the back wall, and it’s kind of impossible not to respect the sheer nerve of it.

Then the 2008 documentary “Anvil! The Story of Anvil” showed up and kicked their story back into public view. Sacha Gervasi directed it, and he doesn’t treat Lips and Robb like museum pieces—more like two stubborn engines that never learned how to switch off. The film didn’t magically turn them into arena kings, but it did something more interesting: it reminded people that Anvil were still out there, still touring, still making records, still refusing to take the hint. Which is either admirable… or deeply unhealthy. Depends how loudly you like your metal.