"Hörzu" The history of Germany's Popular Magazine

I don’t think Hörzu “became” a national institution so much as it quietly moved in and refused to leave. Postwar Germany was rebuilding everything — houses, routines, even the idea of a normal week — and there it was: a weekly paper planting itself right on the living-room table. It starts in 1946 as a radio-program guide, which sounds humble until you remember what radio was then: the room’s heartbeat. Hörzu didn’t preach. It just pointed. And people followed.

By 1950 it’s already pushing one million in circulation. That’s not “growth,” that’s a habit forming. Then the numbers get almost rude: about 4.2 million copies in 1962, with one media study saying it was read by “every third” West German. Around 1969 it crests at roughly 4.3 million, and the same study frames it as Europe’s highest-circulation magazine at the time. At that point you’re not buying a magazine. You’re participating in a weekly ritual whether you admit it or not.

The 1970s and 1980s don’t magically grant Hörzu its power — they just make the power visible. Television stops being a novelty and starts acting like the second fireplace. Color shows up, variety multiplies, and suddenly the week is organized around broadcast hours the way it used to be organized around train times. Hörzu doesn’t “cover” that shift. It rides it, like it planned the whole thing.

And then there’s the ceremonial flex: the “Goldene Kamera” award, introduced in 1965. That’s Hörzu stepping off the sidelines and onto the stage, going from “here’s what’s on” to “here’s what matters.” Even later, the print run stays absurdly big — the German-language record gives 4,438,600 copies for 1979. Nobody prints that many copies for a niche. That’s furniture-level presence. You don’t notice it until it’s gone.

In the 1980s, the air gets noisier. More channels, sharper competition, audiences splintering into smaller and smaller tastes. Hörzu still hangs on, partly because it has a recognizable personality — including Mecki the hedgehog mascot — and partly because it leans into what it’s always been good at: comfortable, mainstream entertainment served with a reassuring sameness. Not edgy. Not trying to impress you. More like, “Relax, I’ve got the week handled.” Which is either comforting or mildly annoying, depending on your mood.

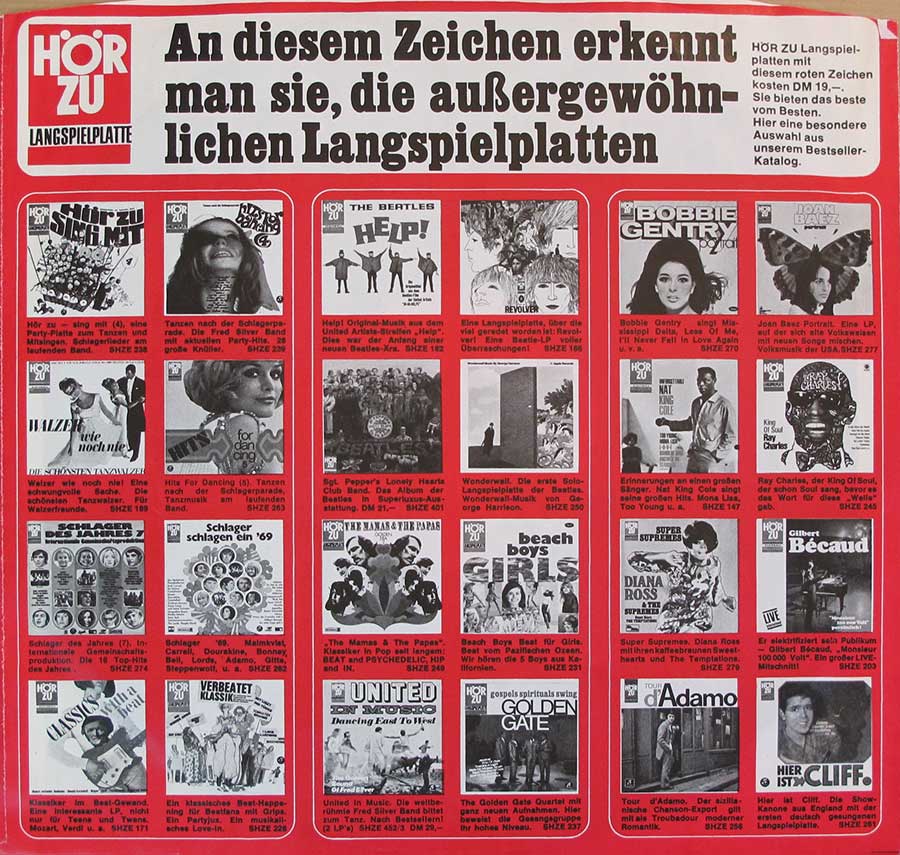

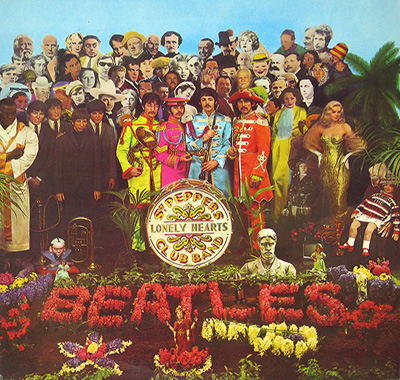

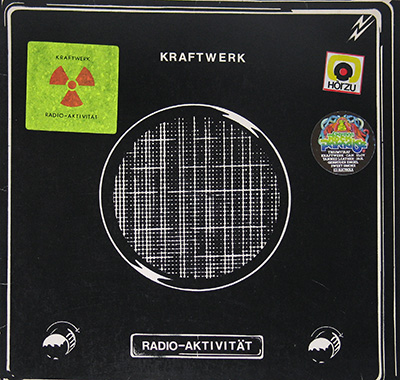

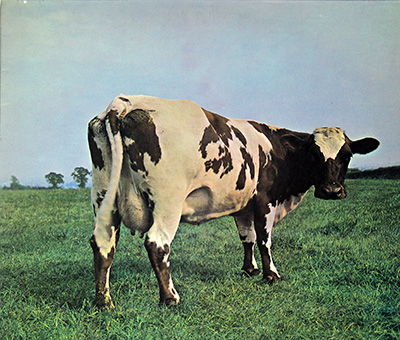

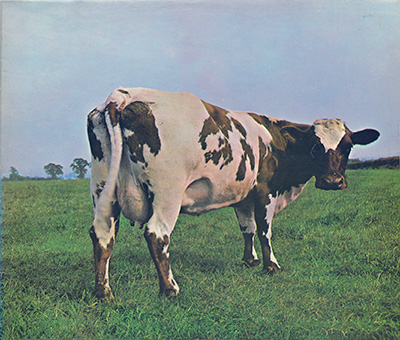

People love to add the little disclaimer: “It wasn’t a music magazine.” Fine. But it still got its hands on music in a very direct way. The English-language record notes Hörzu produced and released LPs from 1963, tied to Electrola in Cologne — which is basically the magazine saying, “You know what? We’re not just listing culture. We’re selling it too.” Then in 1968 it goes further and launches “HÖRZU Black,” aimed at more progressive and avant-garde material. That’s the fun part: the safe weekly guide also had a darker little side-pocket for the adventurous stuff. People contain multitudes. Magazines do too.

The covers help explain why it stuck. During the 1970s and 1980s, the German-language record points out that artist Jörn Meyer painted 65 Hörzu cover images in a naïve-painting style — and that run both boosted his reputation and supported the magazine’s popularity. Sixty-five covers is not a “collaboration,” it’s a whole era of visual wallpaper. You see that kind of imagery over and over — kitchens, waiting rooms, kiosks — and it stops being “art.” It becomes background memory. The kind you don’t realize you’ve stored.

Later, Axel Springer press material still talks up Hörzu’s reach, pitching it as a leading weekly program magazine in Europe with millions of readers. Corporate language always tries to sound eternal, which is cute. But the real point is simpler: Hörzu lasted because it sat where schedules, celebrities, and shared leisure all bumped elbows. Not glamorous. Just effective. Like a well-used remote with the labels worn off.

So yeah, in the 1970s and early 1980s Hörzu isn’t a “trend.” It’s infrastructure — the weekly dashboard for the German living room, where TV, radio, and even record-buying lived in the same evening ecosystem. In my head, it’s always the same picture: the latest issue folded once, corners getting soft, somebody circling a program with a pen that barely works, and everyone pretending they’ll throw it away on time. They never do. Of course they never do.