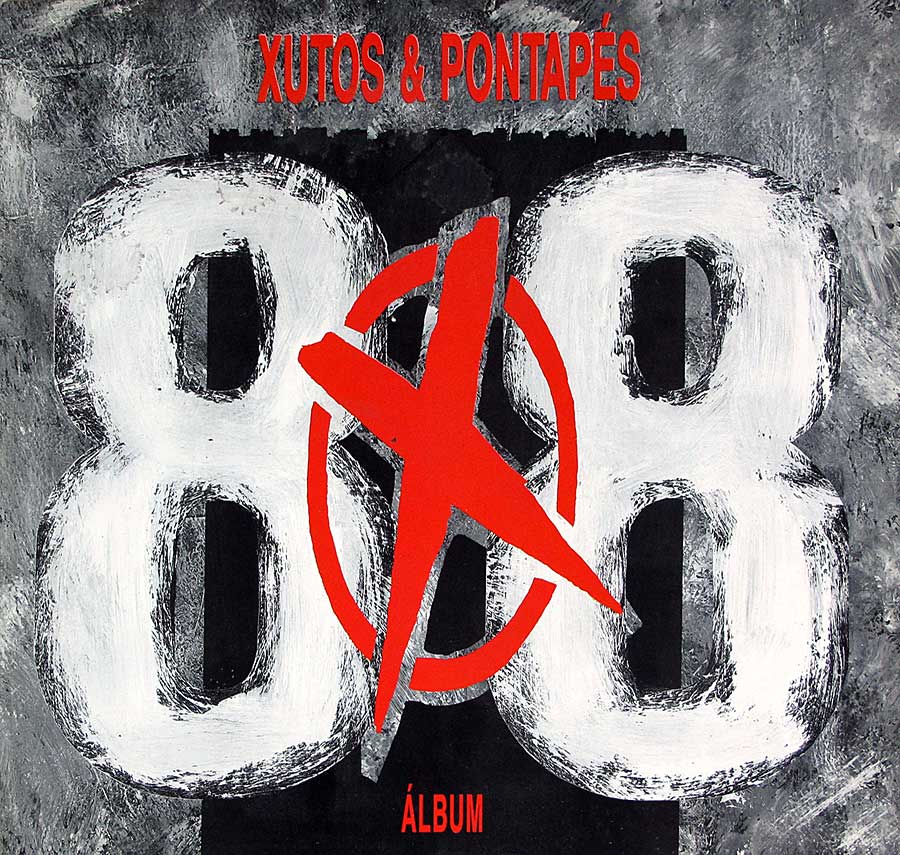

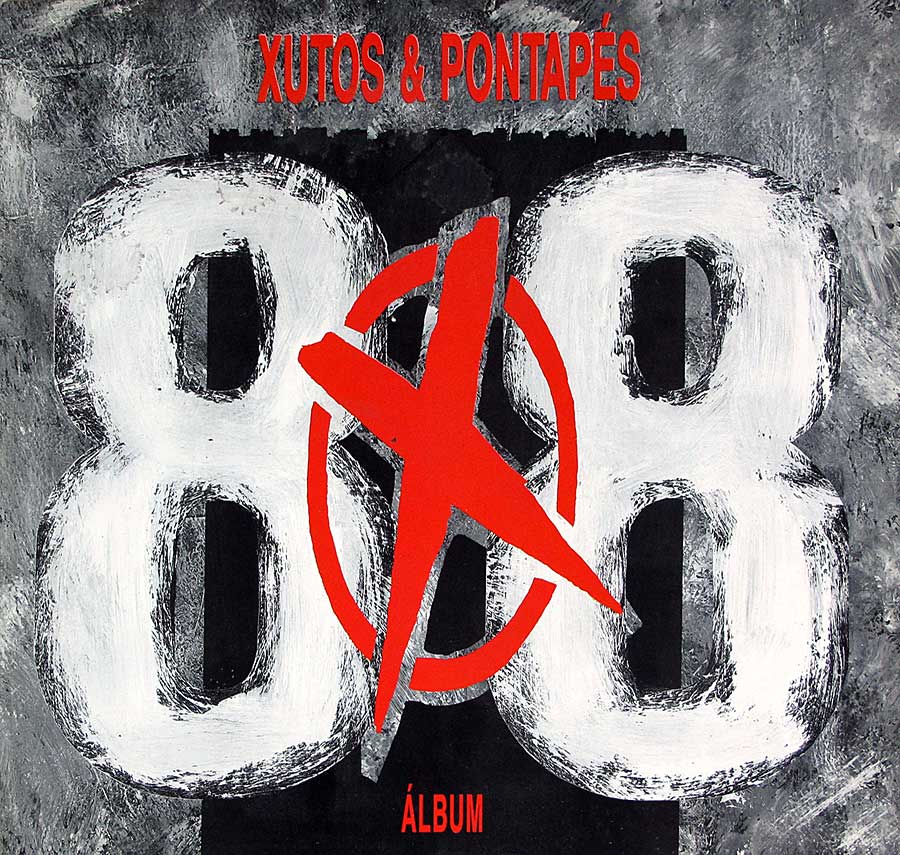

"Album 88" (1988) Album Description:

In 1988, Xutos & Pontapés hit the point where Portugal could no longer pretend rock was a novelty act, and Album 88 is the document of that moment. It sounds bigger, tighter, and more ambitious than their scrappier earlier records, without losing the band’s street-level pulse. This is the album where singalong hooks and punk urgency stop competing and start working together. If you want the cleanest snapshot of Portuguese rock growing up fast, this is it.

Portugal in 1988: the volume knob gets turned up

Portugal was a decade-plus past the Carnation Revolution, and the country was sprinting through modernization after joining the European Economic Community in 1986. The mood on the streets was a mix of opportunity and friction: new money, new media, new cultural confidence, and a youth audience that wanted its own language on the radio. Rock in Portuguese wasn’t just viable anymore; it was the smart move if you wanted to be heard outside a tiny scene.

By the late ’80s, the earlier shock of “rock português” had matured into a real ecosystem of clubs, labels, and national conversation. Acts like Rui Veloso, UHF, GNR, and Heróis do Mar had already proven that local rock could sell, and the next wave pushed harder on attitude and volume. Xutos & Pontapés didn’t arrive from nowhere; they arrived from the same messy, hungry cultural acceleration as the country itself.

Genre map: punk roots, rock ambition, Portuguese voice

Xutos & Pontapés live in that useful overlap where punk is an engine, not a costume. The tempos and chord punches still carry punk DNA, but the arrangements aim for arenas: bigger choruses, sturdier grooves, and melodies built to travel. The sound sits closer to hard-driving rock with punk momentum than to hardcore extremity, and that middle lane is exactly why the record lands with so much force.

In 1988, punk and post-punk around Europe had already splintered into multiple directions, but Portugal’s story had its own timeline and its own urgency. You could feel the scene tugging between underground bluntness and professional polish, between the club and the national stage. Album 88 doesn’t pick one side; it makes the argument that you can be direct and disciplined in the same breath.

Band history: from late-70s Lisbon punk to a sharpened 1988 lineup

The band formed in late 1978 in Lisbon, initially with Zé Pedro, Kalú, Tim, and vocalist Zé Leonel, and their early identity was explicitly punk. After Zé Leonel left in the early ’80s, Tim took over lead vocals while staying on bass, and the group began reshaping itself for a longer run. That shift mattered: it pulled Xutos toward songwriting that could carry both impact and longevity, without sanding off the edge.

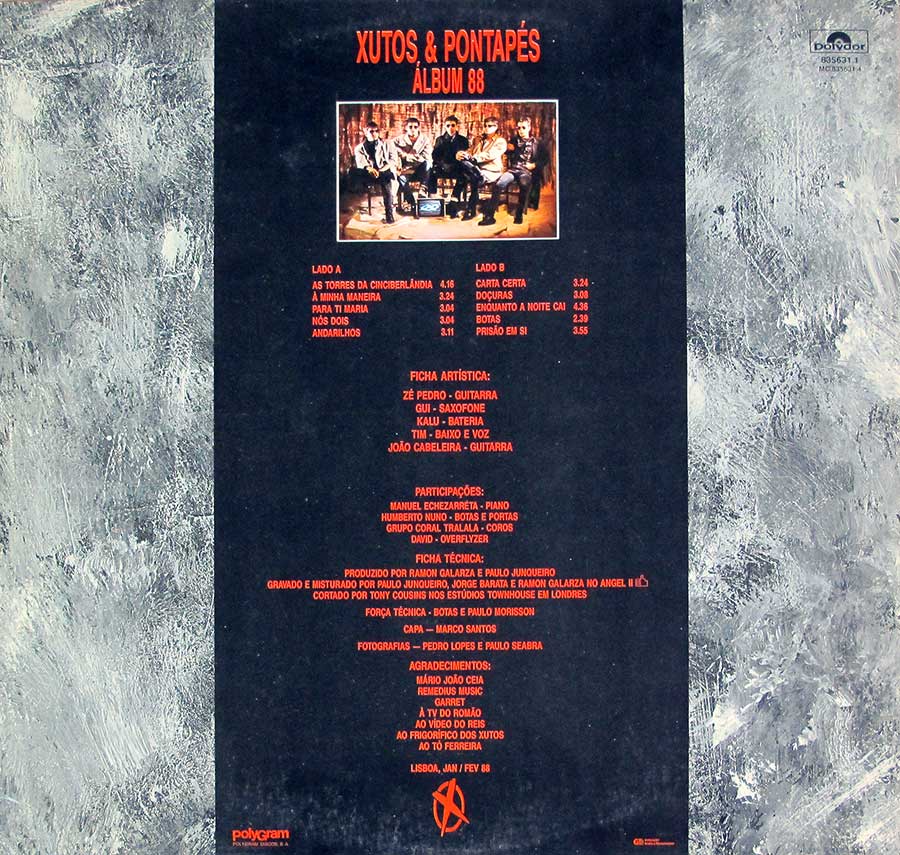

By the time Album 88 arrived, the core lineup had locked into a shape that could handle bigger musical moves. Tim was front-and-center on vocals and bass, with Zé Pedro driving rhythm guitar, João Cabeleira adding lead-guitar bite, Gui coloring the sound with saxophone, and Kalú anchoring it all on drums. It’s a lineup built for forward motion, not just survival.

“Too perfect for a punk band.” That was the complaint. The better question was: why should urgency require bad engineering?

The recording: the people who made it hit harder

A big part of the record’s leap is the first collaboration with producers Ramón Galarza and Paulo Junqueiro, who push the band into a more controlled, high-impact sound. Junqueiro also handled major recording and mixing duties, which helps explain the album’s unified punch. You can hear decisions being made on purpose: where the guitars sit, how the drums cut, how the vocals stay clear even when the band gets loud.

That polish wasn’t about cleaning the band up for polite company; it was about making the songs land with maximum force. The rhythm section feels locked, the guitars are bright but tough, and the arrangements are paced to keep momentum up without turning every track into the same sprint. It’s the sound of a band realizing that craft can be a weapon.

Musical exploration: hooks, covers, and a wider emotional range

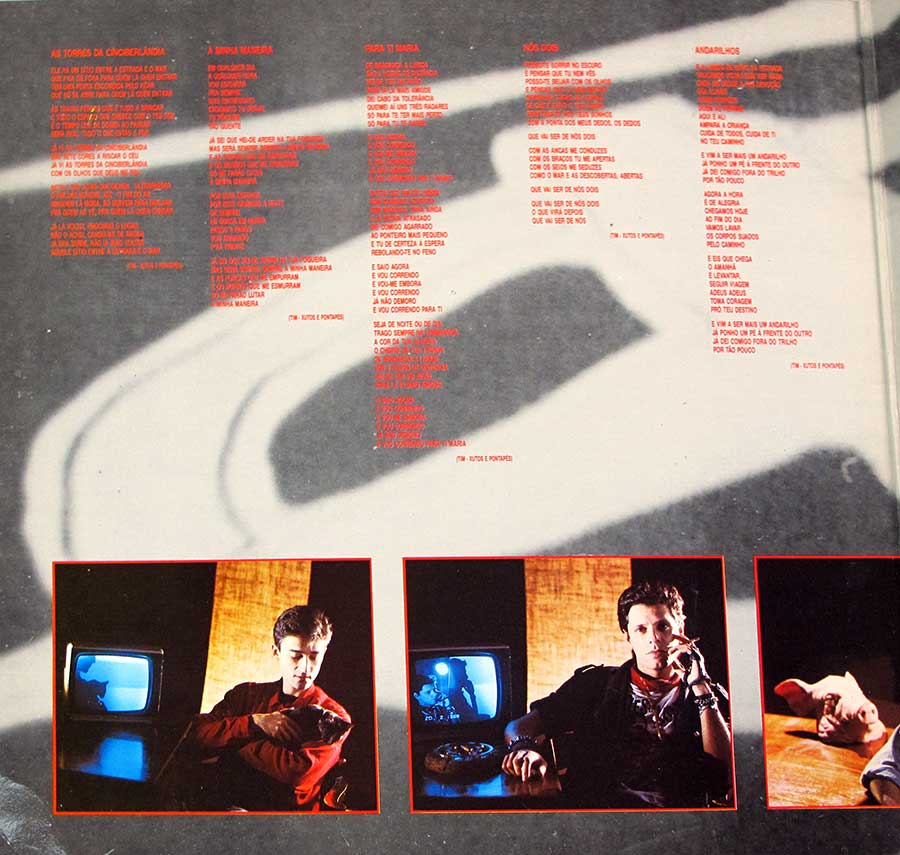

The record moves like a night out that keeps changing neighborhoods without losing the plot. Songs like À Minha Maneira and Para Ti Maria show how Xutos could write choruses that feel inevitable, not manufactured. The band also stretches its palette, letting melody do more of the work while still keeping the attack up front.

Then there’s A Minha Casinha, a classic tune with a long pre-rock history that the band reinterprets rather than merely performs. Dropping a familiar, older song into a modern rock record is a risky move, because it can smell like a gimmick. Here it plays more like a statement: Portuguese rock doesn’t have to borrow its identity from elsewhere; it can remix its own cultural furniture and make it hit.

Standout tracks: where the album shows its teeth

Para Ti Maria is the kind of track that turns a crowd into a choir, built on direct emotion and a chorus designed to be shouted back. À Minha Maneira balances swaggering confidence with a tight, driving structure that never wastes a bar. And Enquanto a Noite Cai brings a darker, late-night tension that gives the album more depth than a simple punch-and-run.

- Hook power: choruses written to survive loud rooms and bad PAs

- Band chemistry: bass-and-drums push the songs; guitars and sax add bite and color

- Range: urgency stays, but the moods expand beyond pure attack

Controversies: not scandal, but a real fight over what “authentic” means

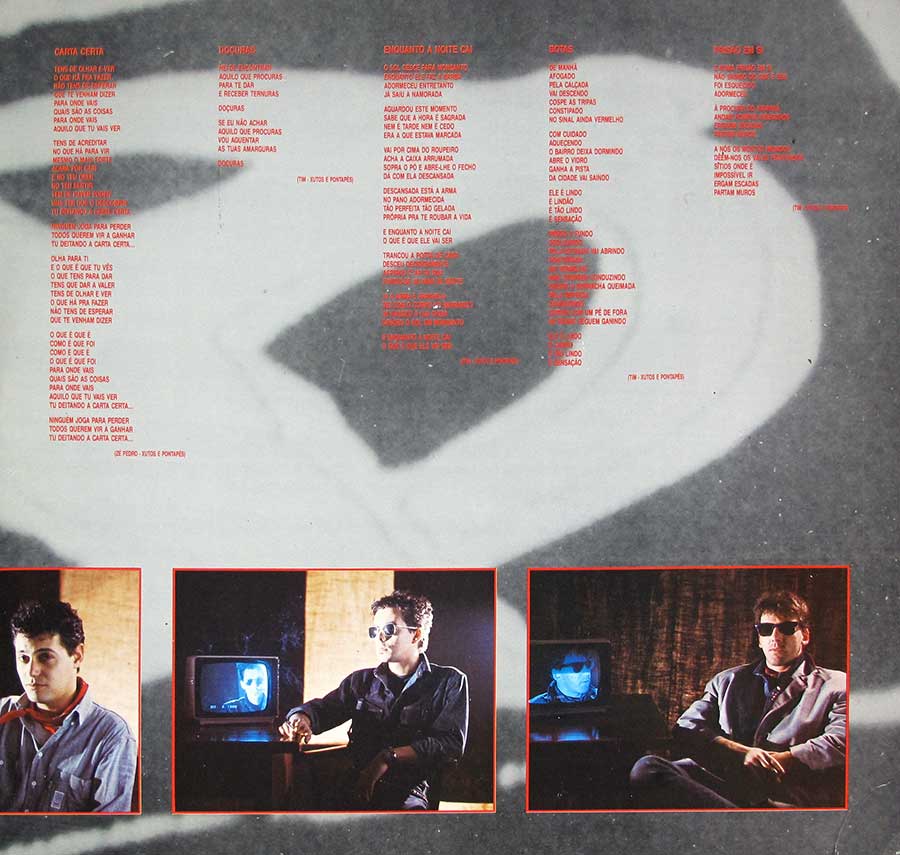

The album didn’t explode because of some tabloid scandal; it sparked a more interesting argument inside rock culture. Some critics and scene loyalists saw the tighter, more technically precise sound as a threat to the spontaneity that punk-coded bands were supposed to protect. In other words: if it’s done well, it must be fake—which is a very convenient way to avoid learning how to play.

The other flashpoint was philosophical, not legal: the band’s choice to blend a broader Portuguese song tradition into a rock framework. For purists, a cover like A Minha Casinha could look like a concession to mainstream taste. For everyone else, it sounded like the band claiming more territory, refusing the idea that Portuguese rock had to stay trapped inside one narrow, imported definition.

External listening and background

If you want to triangulate the album inside the late-’80s Portuguese rock explosion and hear the surrounding weather, these are good starting points. They’re not required homework, but they make the map clearer.