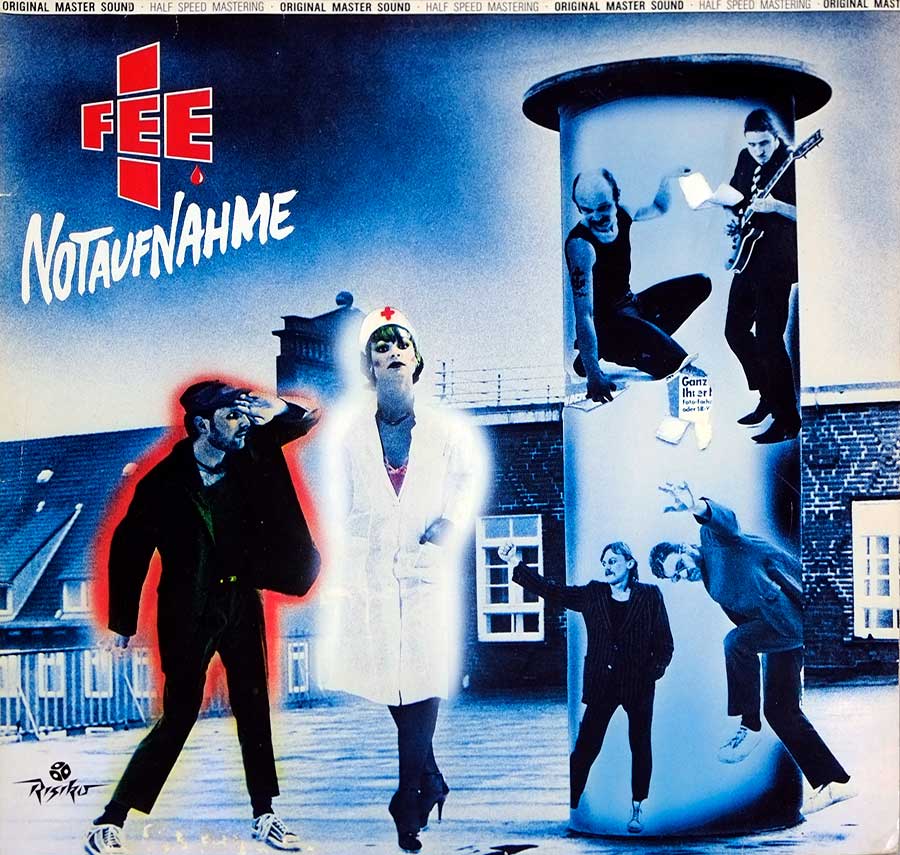

"Notaufnahme" (1981) Album Description:

FEE’s "Notaufnahme" doesn’t stroll into the early-’80s NDW party with a polite handshake; it shoulders the door and starts talking fast. Two vocalists trading lines like they’re cutting each other off, guitar kept sharp instead of heroic, keyboards bright enough to feel slightly clinical, drums locked in with that anxious bounce NDW loved when it wasn’t busy pretending it didn’t care. It’s German New Wave with a pulse and a bit of a mean grin, recorded and mixed by people who understood that “clean” and “alive” aren’t the same thing.

West Germany, 1981: what the air felt like

West Germany in 1981 wasn’t a relaxed place to make pop music, even when the synths were smiling. The country had Cold War hardware in the headlines and a loud peace movement in the streets; that tension seeped into clubs and rehearsal rooms, where everything sounded a little tighter, a little more impatient, a little more “mach schneller.” NDW fed off that mood, part Spaß and part Krawall, with a stubborn refusal to do Anglo-American rock cosplay.

That matters here because "Notaufnahme" behaves like it knows time is limited. The grooves don’t lounge, they move. Even when the hooks are catchy, the delivery stays clipped and slightly skeptical, like the singer is already rolling their eyes at the next line.

Where it sits in NDW without getting precious about it

NDW had plenty of angles in 1981, from art-school sarcasm to hard-edged body music to radio-friendly bounce. FEE land in the lane where the band still sounds like a band, not a studio concept with rented hairstyles.

- Compared with DAF, this is less mechanized and more conversational, more human breath between hits.

- Compared with Fehlfarben, it’s more wired and punchy, less grey-sky post-punk drift.

- Compared with Ideal, it’s less poised, more schraeg around the edges, like the songs were tested live and corrected on the fly.

- Compared with Trio, it’s busier, with more moving parts and fewer blank stares.

- Compared with Nena’s pop-facing side of the era, FEE keep the bite in the vowels.

What it sounds like when the needle drops

The attack is brisk and upfront, the kind of sound where the drums feel close enough to count the stick hits. Guitar doesn’t bloom; it cuts, then gets out of the way. Keyboards act like neon tubing in a stairwell, bright, narrow, and slightly cold, filling gaps without turning the whole room into fog.

The vocals are the tell: two voices, not harmonizing like a choir, more like a debate that refuses to become polite. That push-pull keeps the songs from turning into novelty, even when the titles flirt with it. NDW at its best always sounded like it was in a hurry to make its point and then disappear into the crowd.

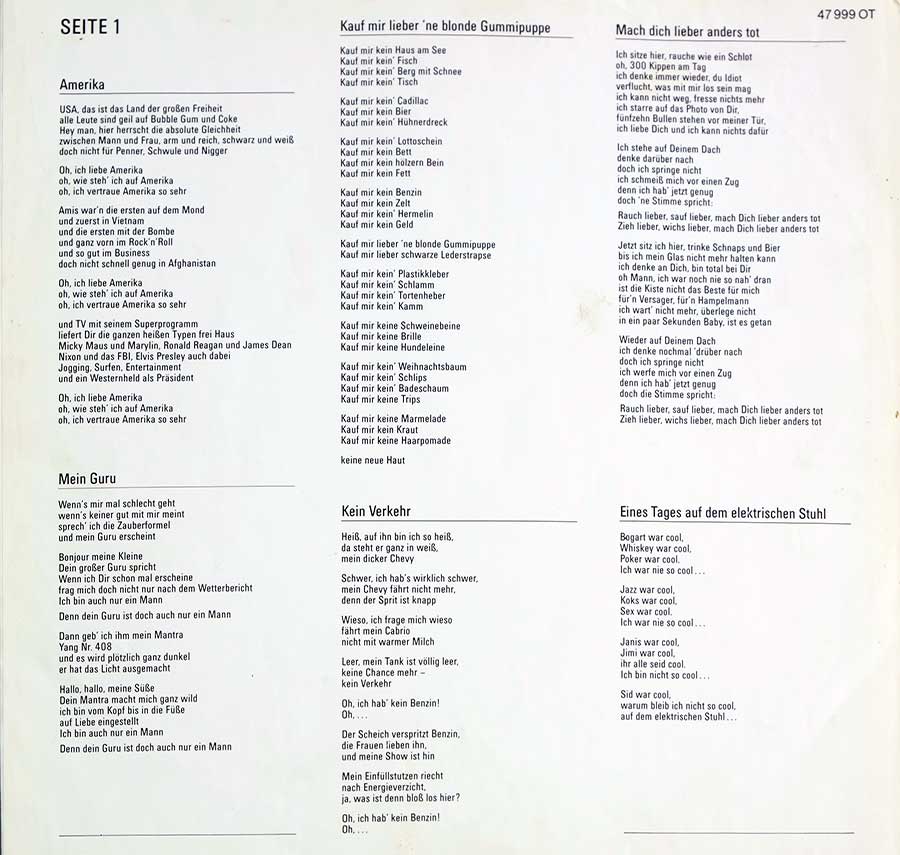

"Overdrive" is the obvious jolt: it leans into speed and tension, the rhythm section pushing like it’s late for something. "Amerika" and "Mein Guru" snap with that sly momentum NDW used when it wanted to sound catchy and critical in the same breath.

Who actually made it sound like this

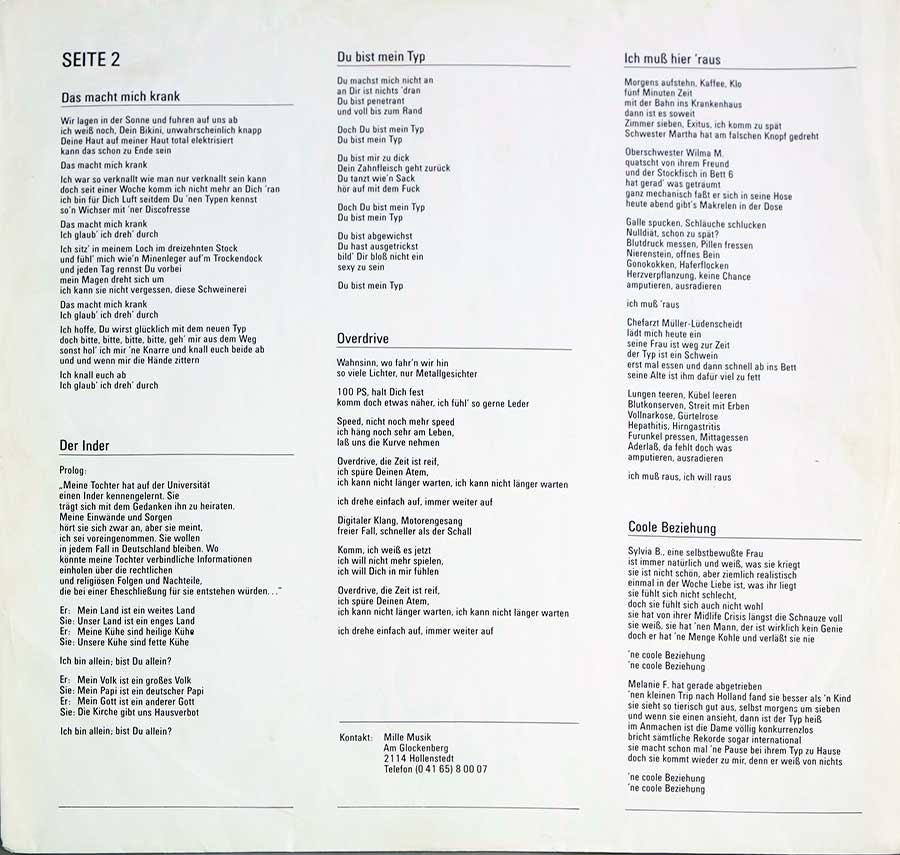

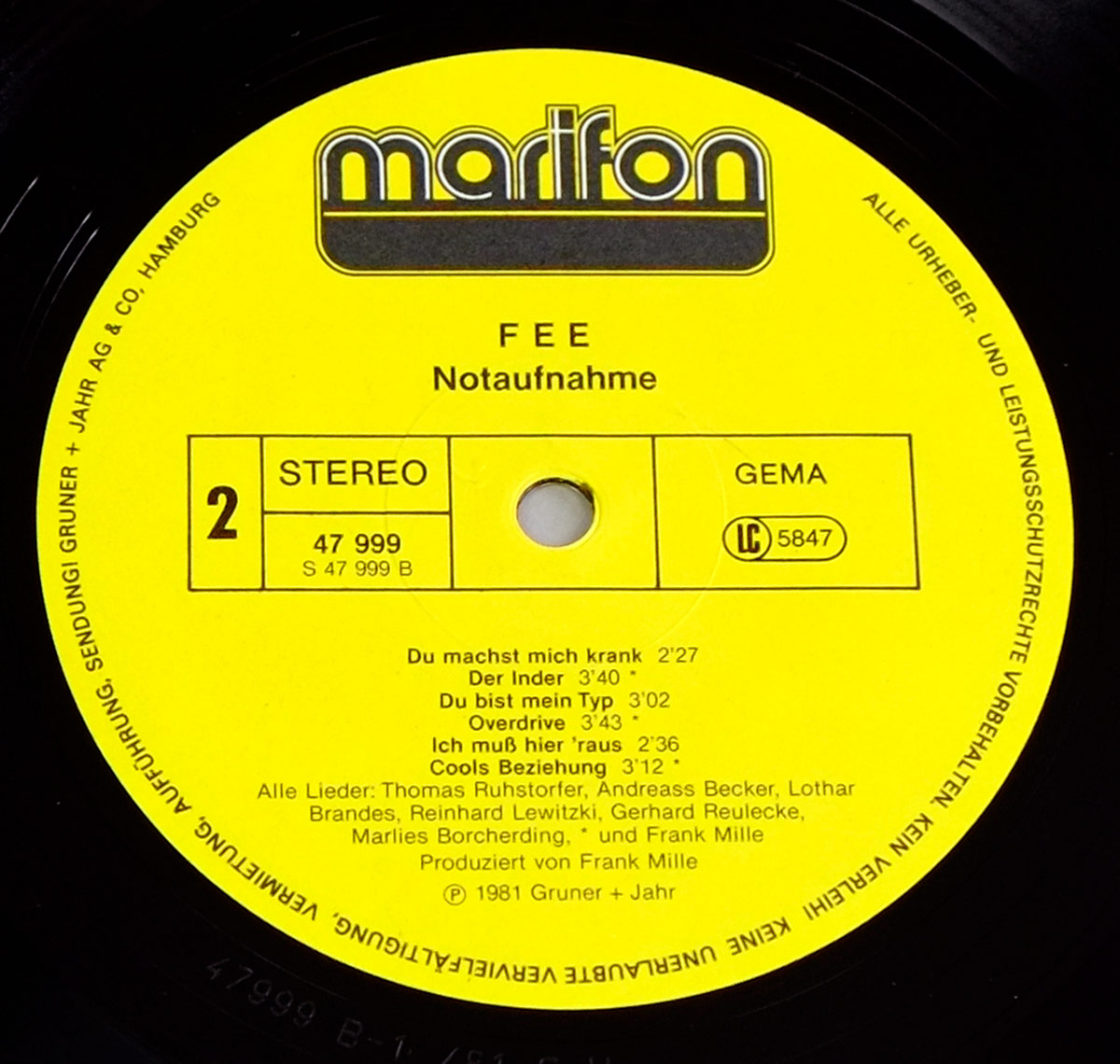

Frank Mille is credited as producer, and the record behaves like a producer record in the practical sense: lean balances, little patience for sludge, and a clear decision about what sits forward. Recorded at Mille Musikstudio, mixed at Studio Maschen in Maschen with Bernd Joost, the chain reads like people who cared about immediacy more than atmosphere. That’s not a philosophical stance; it’s a set of decisions that keep the rhythm section tight and the vocals right in front of you.

The credits also show a band that didn’t hide behind mystery. Names, roles, and track times are laid out like paperwork, which fits the NDW habit of acting casual while controlling the frame. It’s not romantic, but it’s honest.

The messy part: lyrics, provocation, and the misconception people cling to

No fake controversy is needed here; the printed lyrics already do enough damage on their own. "Amerika" contains offensive racial slurs on the inner sleeve, and anyone pretending it’s “just cheeky NDW satire” is working too hard to excuse it. Satire doesn’t get a free pass just because the tempo is bouncy.

The more useful way to read it is as a document of what some people thought they could get away with in 1981, especially when the scene rewarded shock and speed. That doesn’t make it admirable; it makes it revealing, and it’s worth saying out loud instead of polishing it into trivia.

A small, quiet anchor

Late night, small radio, the kind of signal that fades when a truck passes, this is exactly the sort of record that would make you sit up because the vocals sound like they’re talking at you, not performing for you. Next day, you’d find it in a shop bin under “NDW,” half the staff dismissing it, the other half smirking like they’d found a secret.