"Zynobeat" (1989) Album Description:

"Zynobeat" lands like a small-country curveball in the late-80s New Wave shuffle: tight, restless, and allergic to polite background music. B4 Nothing come out of Switzerland’s Rheintal/St. Gallen orbit with a rhythm section that wants to move, a guitar that likes corners more than chords, and just enough horns and percussion to keep the songs breathing like they’re happening in a room, not a laboratory.

Switzerland, 1989: clean streets, messy nights

Switzerland in 1989 isn’t screaming revolution in the newspapers, but the rooms where bands play never cared about the national brand image anyway. The trick was circulation: small scenes, a lot of cross-border listening, and radio that could still surprise you between the obvious hits. By July ’89, "Zynobeat" is turning up on DRS 3 playlists out of Basel, wedged into the same weekly chatter as international pop and rock like it belongs there (because it does).

That’s the vibe: a band from a place people imagine as quiet, delivering music that’s busy, nervous, and kind of smug about it. Not “look at us, we’re Swiss,” more like “look at you, assuming we wouldn’t make trouble.”

Where it sits in New Wave (and who it argues with)

"Zynobeat" lives in that late-80s zone where New Wave stopped pretending it was just skinny ties and started flirting harder with funk muscle and rock bite. If you need a mental map, think of the tense groove-logic you’d get from bands that liked rhythm as much as riffs: the sharp angles of Gang of Four, the art-funk swing of Talking Heads, the Manchester-adjacent pulse of New Order, the synthetic pop sheen of Pet Shop Boys, and the moodier edge circling The Cure.

B4 Nothing don’t copy those bands so much as steal a few good habits: keep the tempo honest, keep the groove impatient, and let the vocals sound like a person trying to get a point across before the room changes its mind.

The sound: attack, space, and that “don’t blink” momentum

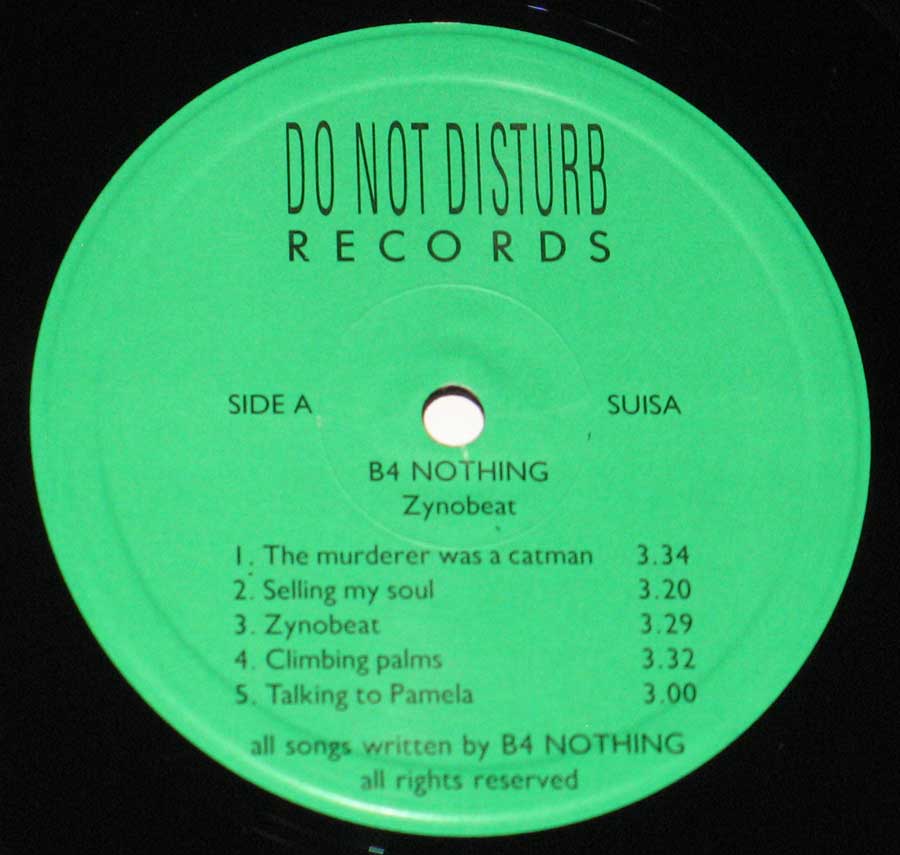

The core lineup is built for forward motion: Enrico Rutz up front; Tom Littleship handling guitar and vocals; Niki Lippuner on bass; Mike Weilenmann on drums. Then the guests show up like a second hand on a clock: Patt Wettstein on percussion, Edi & Beat on horns, Walter K adding vocals, and Dani Ruhle dropping “keyboard noises” that feel less like decoration and more like weather in the room.

The feel is physical: bass lines that walk instead of pose, drums that snap rather than bloom, and guitar parts that jab at the edges to keep everything from getting too cozy. When the horns come in, they don’t “sweeten” anything (thankfully); they puncture.

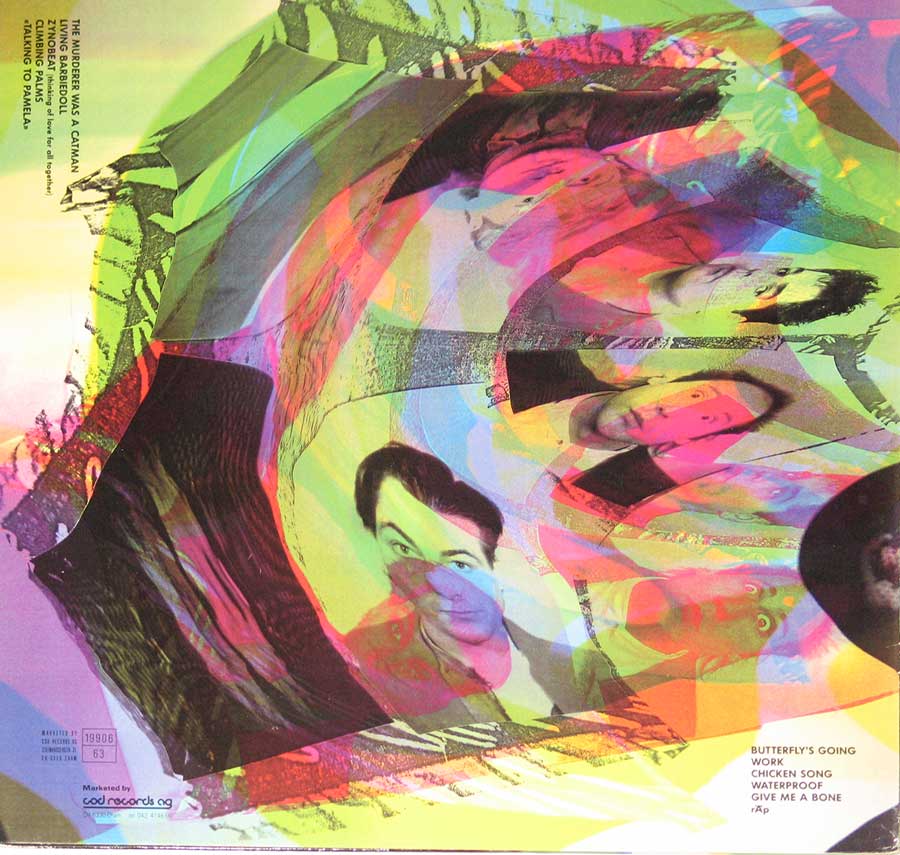

Three tracks that tell you what you’re dealing with

The titles alone give away the band’s attitude, and the album follows through. "The Murderer Was A Catman" kicks the door open with that half-smirk storytelling energy: absurd on the surface, sharper underneath. "Selling My Soul" has the kind of hook that doesn’t need melodrama; it just keeps pushing the chorus back at you until you either admit you like it or start lying to yourself.

And the title track, "Zynobeat," is the thesis: a beat that leans into cynicism without collapsing into it, like they’re dancing while rolling their eyes. It’s not nihilism; it’s stamina.

Who did what (the practical, not the myth)

The production credits are refreshingly direct: produced by B4 Nothing with Walter K, recorded by Hansjurg Meier at Tonspur in Buchs, and mixed by Dani Ruhle at Masters in St. Gallen. That reads like a band keeping its hands on the steering wheel instead of handing the keys to some studio personality with a haircut and a manifesto.

- B4 Nothing / Walter K (production): the choices stay close to the band’s intent, with a band-led feel rather than a “producer’s concept album” vibe.

- Hansjurg Meier (recording): captures a lineup that’s built around groove and timing, not studio trickery.

- Dani Ruhle (mix + keyboard noises): shapes the edges and adds texture without turning the songs into special effects.

Band movement: lineup as cause and effect

The cleanest way to understand this record is to look at the band’s continuity. SwissPunk’s discography notes B4 Nothing releasing "Rheinvalley-Call" in 1987, then arriving at "Zynobeat" in 1989 with a focused core lineup anchored by Rutz, Littleship, Lippuner, and Weilenmann. That two-year step matters: you can hear (and see in the credits) a band tightening the machine while still leaving room for guests to rough up the surface.

It’s not a romantic “they grew up” story. It’s more practical: a band figures out which people make the songs move, then builds the album around that engine.

Controversy: none, but plenty of confusion

There’s no documented scandal attached to "Zynobeat" in the sources that actually bother to list facts. The bigger problem is the boring kind: name confusion. People mix up artist and title (B4 Nothing vs. "Zynobeat"), which is the sort of mistake you make when you’ve seen the name once, at 2 a.m., half-asleep, scribbled on a playlist log or a shop receipt.

Still, that confusion is almost flattering. It means the name stuck, even when the listener didn’t.

One quiet anchor (because real listening happens somewhere)

Picture late-night radio in ’89: DRS 3 out of Basel, the DJ moving fast, not over-explaining, tossing "Zynobeat" into the stream like it’s normal. You sit there with a cheap speaker, wondering how something this wired came out of a country everyone thinks is asleep.