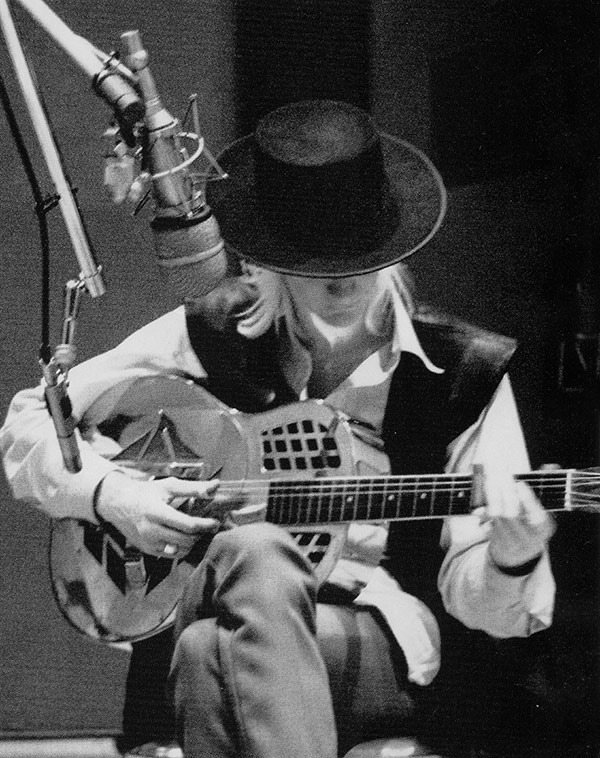

In the late Sixties, the explosive albino bluesman Johnny Winter was considered the fastest guitarist on the planet and hailed as Jimi Hendrix’s equal. With the fresh reissue of his first two albums, Guitar World revisits the groundbreaking work of this essential player.

BY Andy Aledort

" THE EXPLOSION OF THE YOUTH CULTURE in the late Sixties was real surprising to me ," says guitarist Johnny Winter. "It was an amazing time, because things were changing so much, so fast. It was a great time for me and my group to come onto the scene and play the way we really wanted to play." In fact, the time was perfect for Johnny Winter. The late-Sixties culture put an emphasis on individuality: looking, acting and sounding different, and doing one's best to stand apart from the status quo were encouraged, appreciated and, in the music world, often rewarded with fame. Winter scored high on all counts. A white-haired, rail-thin guitarist from Beaumont, Texas, Winter was blessed with unprecedented gifts: he was a blindingly fast virtuoso picker and slide player and an explosive singer and mad-genius interpreter of the blues. Moreover, he looked as if he'd arrived from another dimension. His effect on people was immediate and compelling.

"I first met Johnny Winter in 1968," recalls bassist Tommy Shannon, a member of Johnny's band from 1968 to '69 and, later, of Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble. "I thought he was superhuman. I had never seen an albino before, and he looked beautiful to me, like an angel. When he started to play and sing, it was the most powerful thing I had ever heard. He was like a god."

Twenty-four years old at the time, Winter was already a seasoned professional; he'd been performing live since the age of seven and recording since he was 11. In his youth, he began amassing an encyclopedic knowledge of blues guitar styles, spending "every penny of my lunch and grass-cutting money buying every blues record I could find," he says, "from the earliest rural field hollers to the most sophisticated jazz/blues. I became totally fascinated by it." Ironically, by the time Shannon met him, Winter had given up on pursuing a career in blues music. When Winter, Shannon and drummer Uncle John "Red" Turner began performing in Houston, their repertoire favored more commercial forms of music, including Top 40, r&b and pop, with a blues tune or two sprinkled in the mix.

But in 1968, the forefront of rock became occupied by two formidable power trios: the Jimi Hendrix Experience and Cream, featuring Eric Clapton. Both bands twisted the influences of blues and rock into entirely new musical forms. And both were achieving huge success. At the urging of Shannon and Turner, Winter agreed to adopt the power-trio format of these bands, performing high-energy music they dubbed progressive blues. "Red tried to convince me that we could play blues and make a decent living doing it," Johnny says. "I said, 'I know that you can't, because I've tried to for my whole life.'"

"The success of Hendrix and Cream were the main reasons why Red felt so sure about us making it ourselves. We weren't influenced by their music; we shared that common ground before we had ever heard their records. It was more that their success gave us hope and the encouragement to do it. When they were making lives for themselves, and we figured we could do the same thing. Red said that we should play the music we wanted to play no matter how bad the money was, because it would eventually pay off. It turned out Red was right."

In late '68, the then-new Rolling Stone magazine published a lengthy article about Winter, praising his talents and hailing him as a brilliant blues guitarist. Describing Winter as "a cross-eyed albino with long, fleecy hair, who plays some of the gutsiest, fluid blues guitar you've ever heard," the article piqued the interest of music mogul Steve Paul, who took on the guitarist and his group. Winter's rapid-fire ascent to superstardom began with a six-figure signing bonus and the release in early '69 of his first CBS record, Johnny Winter. Confusion ensued from the start with the concurrent release by Imperial Records of The Progressive Blues Experiment, an earlier demo tape that was a strong outing as well. The upside was that Winter suddenly had two solid albums in circulation simultaneously, both receiving prodigious attention. Overnight, a new guitar hero was born.

From the beginning, the similarities between Winter and Hendrix were evident. They even shared a studio associate in producer/engineer Eddie Kramer, known for his work with Hendrix and credited as production consultant on Johnny Winter. "The parallel between Johnny and Jimi is that they were both very striking individuals in terms of their persona," says Kramer. "Both were very much in control of what they wanted to capture on their respective recording sessions. The feeling that Johnny generated in the studio was quite palpable; when you heard him playing, it was powerful as hell, spectacular to watch.

"At that moment in time, Johnny was looked at as the white blues superhero of the guitar. As with all of the guitar heroes, you got the feeling that Johnny was in charge of his own destiny. As a result, Johnny Winter is a classic blues/rock record. It set the tone for the era."

To accurately grasp the magnitude of Johnny's initial impact on the rock scene, imagine a completely unknown guitar player getting on stage with Jimi Hendrix and not merely holding his own but earning Jimi's instant respect. That's exactly what happened on Winter's first visit to New York City, shortly after signing on with Steve Paul. Jimi was so mightily impressed that he immediately began jamming and recording with Johnny at any opportunity with the expressed intention of."

"The feeling that Johnny generated in the studio was quite palpable; when you heard him playing, it was powerful as hell." — producer Eddie Kramer

"...of learning a few things from him.

Johnny’s rise to superstardom was briefly derailed in 1971 when he entered drug rehabilitation. He reemerged in 1973 with the stunning Still Alive and Well and became the highest-paid performer in rock at the time.

Criminally, the passing of time since has not served Johnny Winter’s legacy well. Although he is clearly one of the most innovative and widely influential guitarists ever, he is virtually off the radar compared to the stature of his peers Hendrix, Clapton and Jimmy Page. Two new reissues from Sony/Legacy may help to reinvigorate Winter’s legacy. The label has released Johnny Winter and Winter’s second album, Second Winter, with deluxe packaging and bonus tracks, including Winter’s Live at Royal Albert Hall concert, recorded in the spring of ’70 and included as a bonus disc with Second Winter.

In this Guitar World exclusive, Johnny and his bandmates—Shannon, Turner and Johnny’s younger brother Edgar, who handled keyboards, sax and backing vocals—got together to discuss the heady days that resulted in these magnificent recordings.

...

GUITAR WORLD : Johnny, it’s easy to romanticize your rapid ascent to fame after Johnny Winter was released. But what was life like for you and the band before you were “discovered”?

JOHNNY WINTER : We were starving our asses off! When Tommy, Red and I first got together in Houston, we played mostly pop music—Top 40—and were making a good living. Anything that anybody wanted to hear, we could play it, because you had to be able to play everything in those days to get a good club job. Or even a bad club job! I’d sneak in a blues every once in a while; we could get away with playing [T-Bone Walker’s classic] “Stormy Monday” because people knew it from hearing it on the radio. But there was no money to be made playing blues, as far as I could tell. It was Red who convinced me to give it a try.

GW : Was there a good blues scene in Houston?

JOHNNY : Austin was better, so we moved there and began playing at a place called the Vulcan Gas Company. It had been an old hotel, and it was all torn up, with bats living upstairs—it was a pretty funky place!

It’s also where we recorded The Progressive Blues Experiment, using just a two-track machine and playing live. We played there once every couple of weeks, and we still played regularly at places in Houston like the Love Street Light Circus and Feelgood Machine.

At that time, we were focusing on original...

"Our success boosted our confidence, and we were influenced to experiment more with "Second Winter" and be creative with our originals."

— Johnny Winter"

"arrangements of blues tunes like “It’s My Own Fault” [included on The Progressive Blues Experiment and the reissued Second Winter bonus disc, Live at Royal Albert Hall], “I Got Love If You Want It” [Progressive Blues] and “Good Morning Little Schoolgirl” [Johnny Winter]. But we went from making a decent living playing Top 40 to making next to nothing at all.

GW : How did the fans react to your change from Top 40 to blues?

UNCLE JOHN TURNER : Many of them freaked out. They were shaking their heads, telling him that he was going to ruin his career. We could empty a packed club in five minutes! The truth is, we were the only ones who really believed in what we were doing. We starved till that Rolling Stone article. After the article came out, that same empty club was filled to capacity, with a line out the door.

JOHNNY : People were used to us doing soul [r&b] music, and when we started playing blues-rock and Hendrix songs, they got upset! Unc is really the one who encouraged me to pursue playing blues and blues-based music, because he thought that the success of Cream and Hendrix had paved the way. When it turned out he was right, it was a great, great feeling.

TOMMY SHANNON : Ours really was a “rags to riches” story. We literally went from sleeping on floors one night to living in a mansion the next, playing gigs for $5,000 a night.

GW : Johnny, after Steve Paul tracked you down in Austin, you came up to New York alone in order to secure a record deal. On your first night in town, you sat in with Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper at the Fillmore East [captured on Al Kooper & Mike Bloomfield—Fillmore East: The Lost Concert Tapes (Columbia/Legacy)] for a blues meltdown of the B.B. King classic, “It’s My Own Fault.” What do you remember of that time?

JOHNNY : That time was a whirlwind. I wanted to see everything that I could, all at once.

GW : When introducing you, Bloomfield says, “this here is the baddest motherfucker, man!”

JOHNNY : Mike was an old friend and had been saying good things about me. I remember that the day after playing with him, I went down to the Scene Club and played with Jimi Hendrix.

TURNER : One of the very first things that Johnny did when he got to New York was confront Jimi Hendrix, and they had a serious guitar-slingin’ battle right away. It freaked Jimi out; he didn’t know there was anyone else around as good as he was."

JOHNNY : Within days, Steve started to negotiate with different labels, and there was a “bidding war” between Atlantic and CBS. I ended up going with CBS for a reported $300,000 deal.

TURNER : We thought we’d have to work our way up, but it really was like a “Cinderella” story, from sleeping on floors to sleeping in mansions within twenty-four hours. We didn’t work our way up; we were on top from almost the very start.

GW : At the end of January ’69, the band went to the CBS studios in Nashville to record your debut, joined by blues luminaries Willie Dixon on bass and Walter “Shakey” Horton on harmonica, with Johnny in the production chair. Were there any specific goals for this record?

JOHNNY : With Johnny Winter, I just wanted to put out the best blues record I could, with some originals and some rearrangements of good blues tunes. Ultimately, I was very happy with the way the band played together.

TURNER : Once we started playing with people like Hendrix, we knew we had to find our own musical approach. In the mass of talent that was surrounding us, we had to stand out, we had to be different, and we had to be ourselves, too. That’s when we began developing our way of presenting these ideas based on Johnny’s enormous talent. We chose not to be like Hendrix and Cream, because that’s what Johnny wanted to do. We were looking to apply our roots to something new.

GW : Johnny, your encyclopedic knowledge of blues guitar is well represented on the reissue of Johnny Winter. There are examples of...

"open-tuned acoustic slide guitar [“Dallas,” Robert Johnson’s “When You Got A Good Friend”] and hard-driving electric slide [“Country Girl”]. And then there’s [the Bobby “Blue” Bland chestnut] “Two Steps from the Blues,” which showcases your incredible range as a vocalist.

JOHNNY : I love “Two Steps.” It’s one of my all-time favorite songs. When we put these songs together in the studio, they all came together very naturally. Two of the originals, “I’m Yours and I’m Hers” and “Leland Mississippi Blues,” were just songs that came to my mind at the time we were recording the albums. We worked out the arrangements and recorded the tunes, simple as that.

GW : One of the earmarks of your guitar style is blazing speed and precision, as exemplified by the single-string tour-de-force “Be Careful With a Fool” and your propulsive take on the Sonny Boy Williamson song “Good Morning Little Schoolgirl.”

JOHNNY : Playing with speed just felt right to me, and I wanted to be able to do it whenever I wanted. It really just came naturally. I wasn’t trying to do anything in particular, other than play what I was hearing in my head.

GW : A great many tracks on Johnny Winter, Second Winter and Live at Royal Albert Hall reveal Johnny’s gifts as an improviser. Like the saxophonists John Coltrane and Charlie Parker, he displays an endless wellspring of ideas, delivering streams of perfectly realized riffs, one after another, with a relentless forward propulsion and momentum. This live-wire, open-channel quality to his playing is what puts him in a class all by himself.

EDGAR : I agree. Johnny’s fluidity does remind me of modern jazz players. There is an incessant quality and intensity in what he plays that is unique to him as a guitar player. He never lets up; it’s an endlessly flowing tapestry of long lines, as opposed to leaving space. The relationship of the ideas in his solos, even though there are a lot of notes, does have an inherent sense of construction. In blues and rock guitar, there’s never been anyone else that plays like that.

JOHNNY : We were trying to bring a “fever-pitch” energy thing to the blues, which people were not doing at the time. A good example is the live version of “Tell The Truth” from Live at Royal Albert Hall, which is really good—"

"very high energy. It’s representative of the type of soul/r&b material Edgar and I were doing when we were younger.

GW : What are your feelings on Johnny Winter today?

JOHNNY : It’s my first “real” record and I’m very proud of it. That original lineup with Unc and Tommy is my all-time favorite band, and Edgar’s contributions on saxophone, piano and as an arranger were great.

SHANNON : I am very proud of Johnny Winter. It introduced everyone to Johnny in the first place, and now that it’s been rereleased, it will remind people of his greatness. It’s something of great substance from the past that shouldn’t be forgotten.

TURNER : The passing of time really makes us appreciate this first record so much more. After our struggle, it was wonderful to realize that we were right, and with our very first record we accomplished everything that we’d been striving for. We had set a goal, and we had achieved it. The “hicks from Texas” had really made the big time, something all musicians sort of misguidedly strive for. We had a formula we were committed to and were proud to be with such a talented young man. It was a wonderful, incredible experience.

GW : What happened after Johnny Winter was released?

TURNER : After recording the album, Steve Paul held us back till the record came out, and he had a very organized, planned promotional assault. Once we started working, we played about three jobs a week. He’d borrowed the money—about $20,000, $30,000, which was a lot back then—to promote this project, which kept us going until we started to make some money. Our first job wasn’t till May or June, when we played a big Seminole Indian reservation. Then all of the Pop festivals happened that summer; once a week we’d play for about 100,000 people.

SHANNON : The summer of ’69 was the era of the big rock festival, and we played all of them: the Denver Pop Festival, the Miami Pop Festival, the Toronto Pop Festival and, of course, Woodstock. It was amazing. We shared bills with the greatest bands ever, like Jimi Hendrix, the Who, the Allman Brothers, Blind Faith, Led Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones, Sly and the Family Stone and Frank Zappa.

Life—and the world—was simpler then. It wasn’t hard to get a record deal if you had a really good band. And there was no such thing as corporate sponsorship; the artists created the music and the audience supported the artists. The country was more innocent then; there was less disparity economically."

"...and there was not the terrorist situation like we have today. People lived for the music, and they weren’t asleep; they were active participants in the shape of their culture.

The feeling back in the late Sixties was that there were unlimited possibilities for greatness in life, for good feelings and powerful connections, for everyone. There was a spiritual unity that crossed over from music into every aspect of life.

GW : Did the spirit of the times translate to the music you recorded for your next album, Second Winter?

JOHNNY : Our success boosted our confidence, and we were influenced to experiment more with Second Winter and be creative with our originals. We were discovering new things with the more rock-oriented songs like “The Good Love” and “Fast Life Rider.” I used a wah-wah for both tracks, which is something I hadn’t done before and haven’t done since. On the song “I’m Not Sure,” I used an electric mandolin that was made for me by my friend Minor Wilson. He put a bass pickup on it, and it was a lot of fun to play.

TURNER : The otherworldly vibe of that song can be attributed to the unusual instrumentation: Johnny’s electric mandolin is backed by Edgar on an early synthesizer set to a harpsichord-like timbre. That was an attempt to sound wild, to do something different. Shortly after Johnny got the electric mandolin, Robbie Robertson of the Band saw it and asked him how to get one. It was the only one like it at the time.

JOHNNY : All of the songs came together pretty quick; I never really had to show Unc or Tommy exactly what to play. I’d run a tune down for them and they’d have it right away. I always wanted to get each song recorded within the first couple of times we played it, so that freshness and excitement would be there in the performance. When you play a song too many times and mull over it, it begins to sound worse; it loses its feeling. All told, we did the whole record in about two weeks.

EDGAR : Johnny’s style of recording is very much in the blues tradition. It’s very live, very immediate, and he doesn’t spend a lot of time in the studio. If you don’t get the song in one or two takes, it’s on to the next song! Johnny was the right person to be at the helm.

GW : Second Winter illustrates a great diversity in musical styles: experimental rock [“Memory Pain,” “I’m Not Sure,” “The Good Love,” “Fast Life Rider”], traditional blues [“I Love Everybody,” “Hustled Down in Texas”], swinging jazz [“I Hate Everybody”] and rock and roll standards [“Johnny B. Goode,” “Miss Ann,” “Slippin’ and Slidin’”].

TURNER : In choosing the music for the..."

"...album, we went back and looked at the songs we all loved. It was primarily black music, and that manifested itself in our own music.

JOHNNY : There are a lot of different styles of music on Second Winter. “Memory Pain” is one that we just whipped together for the album. I used a Gibson SG for that track, and it could have been the gold-top Les Paul for most of the other tunes, plus my Fender XII, with six strings on it, for the slide cuts. We were experimenting with recording techniques then, and for “Memory Pain,” we put the guitar amp in the stairwell to get a different kind of a sound.

TURNER : I have never heard the original track; it’s by Percy Mayfield, but I have no idea what it sounds like. Johnny sat there and showed us all of the parts, but he never told us what to play. We naturally interpreted it together.

GW : The guitar tone is pretty distorted on that tune. Were you using a distortion pedal?

WINTER : No, I never have used distortion pedals except on very rare occasions, like on [the unofficially released cut] “Livin’ in the Blues.” I just had the amp turned up real loud.

GW : One of the standout tracks on Second Winter is Johnny’s original composition “I Love Everybody,” which features a great arrangement and a totally original updating of the country blues played electrically, similar in approach to Johnny Winter’s “I’m Yours and I’m Hers.”

JOHNNY : “I Love Everybody” is one of my favorite tracks I ever recorded. It sounds like two different slide guitars on the intro, but it’s really the same guitar, panning back and forth. It’s a funky beat, played with a nice blues feel.

GW : Second Winter also includes the counterpart, the fast swing, “I Hate Everybody.”

JOHNNY : That one was hard to play! There is a lot going on in that tune.

GW : Second Winter’s standout cut is the cover of Bob Dylan’s “Highway 61 Revisited,” which takes its strength from your relentless electric slide guitar fireworks.

JOHNNY : “Highway 61” is a song we did because I’ve always been a big Dylan fan. You can’t be my age without loving Bob Dylan! We’d been doing the song in clubs for quite a while, but I hadn’t done it on slide before. It worked out real well.

UNCLE JOHN : There are a couple of Dylan songs that people have been given credit for improving on. One is Jimi Hendrix’s version of “All Along the Watchtower” and the other is our version of “Highway 61.” Bob now plays “All Along the Watchtower” like Jimi, and he rocks up “Highway 61” pretty good, too. That song still gets loads of airplay today.

GW : When Second Winter was originally released, it was a three-sided double album..."

"...in other words, the second side of the second vinyl disc was blank.

JOHNNY : That shocked people, and the record got a lot of attention because of it. We wanted to put out everything that we’d recorded, and what we had amounted to three sides. The funny thing is, the length of those three sides is about the same length as the average CD today.

GW : This deluxe reissue of Second Winter features as a bonus Live at Royal Albert Hall, a previously unreleased live concert that captures the group at the peak of its powers at the culmination of your 1970 European tour. What do you remember from that time?

JOHNNY : We were real glad to be touring Europe at that time. We felt we had something to prove; we wanted to take our music to every part of the world, if we could. And the crowds loved us over there. It’s a good representation of what we sounded like at the time.

EDGAR : The thing that really stands out to me, on all three new releases, is the energy, invention, originality and the sense of adventure. These records represent the closest Johnny and I came to collaborating. If you listen to the Live at Royal Albert Hall show, Johnny does the first part of the show as a three-piece, and then he says, “Let me bring out my little brother, Edgar!” I was living with the band at the Quadrangle [in upstate New York] and that’s where I first worked up “Frankenstein” [the Edgar Winter Group’s hit single from their 1972 album, They Only Come Out at Night] in its original form. It was a training ground for all of us, but especially for me. This experience gave me the confidence to front my own band and pursue my own style.

I think Live at Royal Albert Hall is an honest representation of our band. A lot of it is very raw, especially for me; I was still searching at the time. But Johnny had been doing his thing for a while, and he is amazing on it. It incorporates the early blues stuff he did with his trio, like “Help Me” and “It’s My Own Fault,” plus things like “Frankenstein,” which represented new ideas. This is what makes it such a vital and interesting release. It makes perfect sense to put the Albert Hall show together with Second Winter, because what we did live was deeply connected to what we had done in the studio.

JOHNNY : I’m real happy people will get a chance to discover, and rediscover, Johnny Winter and Second Winter, and the live Royal Albert Hall show is a great bonus. That period was a very exciting time for us, and I think the music stands up well today.