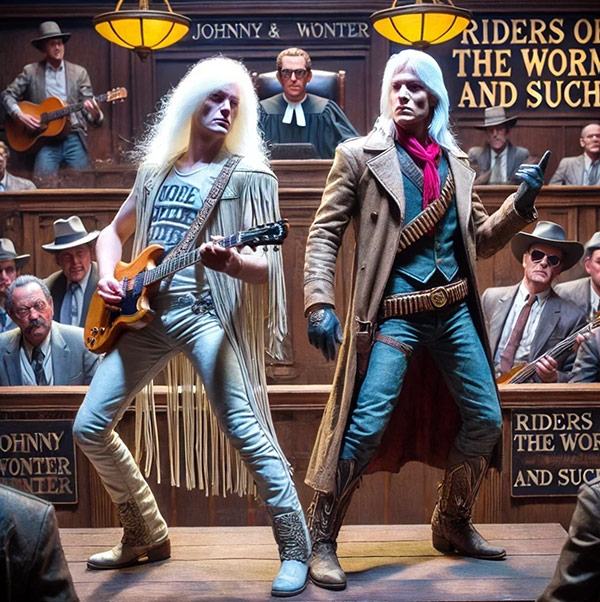

The Whittier Law School and the Motion Pictures Association of America et al. filed Amici Curiae briefs in the suit between musicians Edgar and Johnny Winters and DC Comics, Joe Lansdale, Tim Truman, Sam Glanzman, and DC's parent company, Time Warner. The Amici contain statements that the filers hope the Supreme Court of California will take into consideration before hearing the case on April 1st.

Amici Curriae are simply brief files with the Court for its consideration on a given matter. Organizations with vested interests for either the plaintiff of defendant can file amici.

Going into the background of the case, the matter began in 1996, when the

Winter Brothers filed suit against Lansdale, Truman and Glanzman

, writer, penciller, and inker, respectively, of DC's Jonah Hex: Riders of the Worm and Such

Worm was the second of three Jonah Hex stories produced by Lansdale, Truman and Glanzman - Jonah Hex: Two Gun Mojo was the first, in 1993, Worm was published in '95, and Jonah Hex: Shadows West was published in 1999. The problem with Worm according to the Winters was the creative teams' portrayal of "The Autumn Brothers," Johnny and Edgar, who were half-human, half-worm creatures which were allegedly the offspring of the rape of a human woman by a giant worm. In the three issues in which they appear, the Autumn Brothers are shown as having very light complexions and long white hair, similar to the Winter Brothers, who are albinos. The Autumn Brothers were eventually killed by Hex and his companions.

The Winters filed suit in Los Angeles Superior Court in March of 1996, claiming:

- Defamation of Private Figure

- Defamation of Public Figure

- Negligent Invasion of Privacy (False Light)

- Invasion of Privacy (False Light)

- Invasion of Privacy (Appropriation of Name or Likeness under Civil Code ? 3344)

- Invasion of Privacy (Appropriation of Name of Likeness under Common Law)

- Violation of New York Civil Law ? 51

- Negligence

- Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress

- The Comic Book Legal Defense Fund joined the fight against the suit in May of '96, supporting the First Amendment rights of the creators to use public figures in satire and parody.

As Lansdale said in a CBLDF release, "It was our intent to use the Jonah Hex comic book series as a vehicle for satire and parody of musical genres, Texas music in particular, as well as old radio shows, movie serials and the like. We feel within our rights to parody music, stage personas, album personas, lyrics and public figures."

Shortly after the CBLDF joined the case, DC Comics itself signed on, defending its creators with the legal muscle of Time-Warner. In early 1998, the Los Angeles Superior Court granted summary judgment to the defendants and DC, in essence, throwing out the Winters' complaint.

In granting the summary judgment, the late Judge Ronald Cappai ruled that the series was protected as a parody, and cited Hustler Magazine v. Falwell (1988), in which, the Supreme Court applied First Amendment protection to a Hustler parody piece which suggested that Falwell engaged in an incestuous affair with his mother.

Truman told the CBLDF that the decision by the court was "a victory not only for us, but for any cartoonist who comments upon, or pays tribute to, the legacy of any public figure."

Not So Fast There, Cowboy

The Winter Brothers then appealed the decision, and had amicus brief filed by the National Organization for Albinism and Hypopigmentation in their support. In the appeal, which came down last June, the court upheld its decision to throw out the Winters' claims of defamation, invasion of privacy, and misappropriation of the names and likenesses under California common law ad the claims made under New York Civil Rights Laws, but ruled that the Winters had produced sufficient evidence that Jonah Hex: Riders of the Worm and Such was not "transformative" or a simple parody.

By "transformative," the appellate judge was referring to the Comedy III Productions vs. Saderup case in which the company holding the license for the Three Stooges sued artist Gary Saderup - and won - because the court felt that the artists' interpretations of the Three Stooges had moved from expression into merchandising, and was not transformative of the original subjects. That is, Saderup's image of the Stooges, which had been reproduced on t-shirts and lithographs, showing them not smiling, was no longer expressive art, but instead, commercial speech. As such, the First Amendment doesn't apply to it as it does to expressive speech.

The court in the Comedy III case upheld though, that the First Amendment does protect work that is transformative, and cited Andy Warhol's images of Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, and Elvis Presley as examples of expressive and transformative speech that would be protected. At the same time, the First Amendment, the Court said, does not guarantee the right to make commercial use of "a mere celebrity likeness or imitation." That is, a photorealistic image drawn by an artist for commercial use. Along with the Stooges, Saderup had found himself in a legal battle with Shaquille O'Neil over the same issue - but settled with the big man out of court.

Along with transformation, and the issue of commercial art, the Winters case, as with the Comedy III concerns the legal doctrine known as the "right of publicity." Similar to trademarks or copyrights, the right of publicity grants celebrities or their heirs the sole right to market their names and images.

On these grounds - that the Winters' right of publicity has been violated by the miniseries, the work was not transformative, and that the version of the Winter Brothers was shown in what the Court saw as commercial art - the case came back to life last year, and is now headed for the California Supreme Court.

So - boiling it all down, the core issue is whether California's right of publicity laws can apply to creative speech (which DC, the creators, and the parties who submitted amici contend that's what Worm is). No one is arguing that the right to publicity laws themselves are unconstitutional - just that in this case, the law was never intended to cover artistic expression Even simpler:

Winters:

- (a) Jonah Hex: Riders of the Worm and Such is commercial art.

- (b) The depiction of the Winters Brothers is not transformative, and therefore not a parody.

DC, Worm creators, MPAA, Wittier Law School, et. al.:

- (a) Riders of the Worm is artistic expression, not commercial art.

- (b) The depiction of the Winters Brothers as parody is sufficiently transformative.

As cited in the original court ruling and the Whittier amicus, the Winters' Brothers portrayal in Worm is well, pretty graphic and ugly in both image and deed. Suffice it to say, no one would really want to see themselves made fun of in that manner except maybe.Rob Zombie to pick a name out of the air. Thing is, that's part of the price of being a celebrity. If you place yourself in the public eye, you're allowing yourself to be commented upon, from two people gossiping in the street to a guy at a computer keyboard writing a comic book script and another guy with a pencil in his hand.

It's part of the cost of being a celebrity and living a life in the public eye - for better or worse, and as weird as it sounds, part of "you" belongs to society, and society is free to do with it as it chooses - to a point (commercial exploitation and blatant defamation, for example aren't allowed). It's a weird analogy, but the same laws that the amici signatories feel should protect Lansdale, Truman, Glanzman, et al., protect editorial cartoonists and political commentators as well.

Their Amici, Your Amici, Wouldn't You Like Amici Too?

In the Whittier amicus, Professor David Welkowitz states that the Winters' claim of right of publicity violation is nothing more "than a defamation claim with a different label," and should be dismissed as such. Welkowitz also claims that the appellate court erred when it found Lansdale, Truman, and Glanzman's portrayal of the Winters Brothers not to be transformative.

Welkowitz states: "As this court noted in Saderup, the First Amendment requires that authors, satirists, parodists, and other social commentators be given the ability to lampoon, even tastelessly, public figures, free from the threat of litigation under the rubric of publicity."

That said, Welkowitz then argued that, given their portrayal as half-human, half-worm creatures who appear to have an insatiable appetite for violence and sex, while the real Winters Brothers are human musicians, their portrayal in Worm is sufficiently transformative to stand up under the Saderup decision.

Welkowitz also argues that, while the feelings of the Winters Brothers in light of their "tasteless portrayal" by the defendants is understandable, allowing them to succeed in their claim of right to publicity is "Tantamount to opening a serious, and unwarranted, loophole in the constitutional law of defamation, and would permit celebrities to censor unwanted criticism."

The Whittier Amicus also argues that the comic, while distasteful to some, is fully protected by the First Amendment, citing the appellate court's opinion in Saderup that creations do not lose their constitutional protections because they are for the purpose of entertaining rather than informing, and "the right of publicity derived from public prominence does no confer a shield to ward off caricature, parody and satire. Rather, prominence invites creative comment."

Again, claiming that Worm is, and always was intended to have an element of satire; it cannot be seen as commercial speech.

Interestingly, Welkowitz cited another case near and dear to the comic industry that supports the defendants - Doe vs. TCI Cablevision, or as its more commonly known 'round these parts: Tony Twist vs. Todd McFarlane. Citing that court's decision:

"If Falwell, Twist, or other public figures were permitted to prevail on a "right to privacy' or 'misappropriation of name" without satisfying the New York Times test [which rules that speech which does not state facts but inflicts serious injury to the dignity of a public figure was controlled by the First Amendment, as long as it did not meet defamation criteria], out First Amendment protections would be an illusion. Every public figure, under the guise of 'misappropriation' or 'right of publicity' could circumvent the First Amendment and prevent all speech about them that they do not like. This is clearly not the law."

"Although clearly distasteful," Welkowitz states, "the use of the plaintiff's images in the comic book amounted to a form of social commentary. It is important that we leave breathing space for such commentary, particularly when it is aimed at celebrities."

The MPAA amicus includes, all told: the MPAA, the Association of American Publishers, Inc., Authors Guild, Inc., Publishers Marketing Association, CBLDF, Dramatists Guild of America, Inc., PEN American Center, America Booksellers Foundation for Free Expression and the Freedom to Read Foundation.

The MPAA amicus focuses on four points:

the appropriately high level of First Amendment protection afforded to traditionally protected audio-visual, literary and dramatic works.

The Court of Appeal's disregard of California Civil Code Section 3344's express definitional limitation to "products, merchandise, or goods."

The inapplicability of the "transformative use" test to publicity rights claims based upon traditionally protected expressive works.

The importance of adopting a brighter line and more protective standard for publicity rights claims arising from disputes involving such expressive works.

Citing Saderup as well as Twist and many other similar cases, the MPAA amicus argues along the same lines as the Whittier amicus, reiterating the chilling effect a decision in favor of the plaintiffs would have on First Amendment rights.

Extrapolatin'

And that's the crux - while the case at the center of this, two rock musicians suing over what they feel is an improper use of their likeness in a work of fiction, frankly, couldn't sound more stupid from the outside, the potential repercussions of the decision are huge.

The MPAA and signatories on their amicus are concerned about this case due to the fact that if the Winters' win on their case, any representation of a public figure in any entertainment context would become vulnerable - not to mention comics would be seen, legally, as commercial art and would be offered more limited protection under the First Amendment.

Sure - Samuel L. Jackson and Avery Brooks could sue Marvel and DC, respectively for their likenesses being used in The Ultimates and Stormwatch, but move away from comics and look at the bigger picture. If the Winters' Brothers claim stands, any public figure who did not like the presentation made of them in any given form could sue the creator and distributor/publisher of that work.

What's on the list of works that regularly use transformative images of public figures for expressive use? Editorial cartoons, MAD Magazine, Saturday Night Live, "unauthorized" biographies, and everything in between. Christina and Britney could sue if their images appear in something, even if it's meant as a parody, while George Bush Jr., John Ashcroft, and Donald Rumsfeld could sue cartoonists and newspapers if they didn't like how they were portrayed in the page 5 editorial cartoon - something which has always been an important avenue of political commentary and dissent.

If Winters wins, then could potentially be nothing to stop a well-funded and backed politician from threatening legal action against a cartoonist or newspaper. Rather than risk a loss in court, many papers would most likely settle, and as a part of the settlement, agree to remove the cartoonist, or the editorial cartoon altogether. Do not speak out against Big Brother.

It's a chilling extreme, but not one that is entirely unlikely if the Winters' succeed. - again, all that is needed is a precedent for future cases to stand on to make their argument. It could also be speculated that cases such as this is having a chilling effect on the material (and like materials) seeing print.

Of the three Jonah Hex stories by the creators, and despite being a genre that is outside of traditional superheroes (horror Western) only the first, Two Gun Mojo has been collected into a trade, but is currently out of print. Despite being a participant in the legal battle, it's fairly clear that DC would not want to be publishing a book, or have made money on a project whereupon it was decided that something contained therein broke the law. That is, if Worm was currently collected and in print, and DC and the creators had made money off of it, they could have to pay damages if the court sides with the Winters and awards damages. In a matter such as this, it potentially pays to keep one's head down.

On the outside, a Winters win could also affect a DC decision to collect and publish the Flex Mentallo miniseries by Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely. While specifics in the cases are not exactly the same (the Atlas company was suing DC, rather than individual people), the satirical and parody nature of the work was one of the points on which the Court based its opinion. If the Winters case shows that essentially no representation of a figure can exists as a transformative parody, all it would take would be an enterprising lawyer to take that decision for an individual (the Winters), and apply it to a company, i.e., Atlas.

If you want to go all conspiracy theory, of just a little, Winters v. the Worm crew could easily be seen as a continuation of a fight that's been going on since the victory in Hustler v. Falwell in 1988, in that this form of expression has been targeted by someone, and they are continually trying to knock it down to crush public commentary and dissent as well as expression.

More likely than that however, the Winters case is just the latest in a string of cases with the similar theme - celebrity is made fun of, celebrity doesn't like it, celebrity sues. All told, it's probably something that could be prevented if they would give guidebooks to every celebrity with rules of being a public figure in it. "Rule 1: People can, and will make fun of you - and sometimes, even though you don't like it, it's their right to do so."

That these cases get so high up in the judicial system is telling of their importance in our society, and the lengths that people are willing to go to make sure the law fully reflects their view. Safe to say, if Winters sees a victory in the California Supreme Court, the defendants (with the deepest pockets, that is, Time-Warner) will appeal it to the Supreme Court.