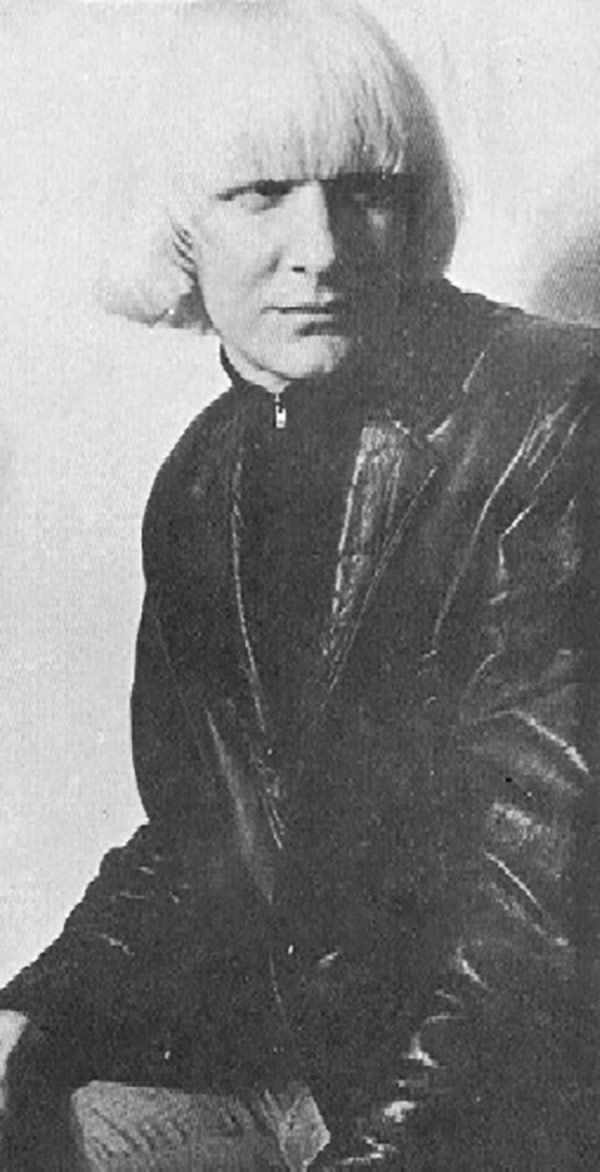

In the summer of 1968, John Sinclair and the MC5 put on something called the Motor City Rock Festival—a ton of bands and three headliners over two nights: The Five, Sun Ra, and Johnny Winter. Sunburned and ornery as only a teenage purist can be, I wanted to skip Winter's set. He'd been hyped in Rolling Stone as an albino celebrigeek, and I figured any guitar player noted for the paleness of his complexion could not be worth much. My girlfriend, who'd already seen Johnny, told me that if we stayed, I'd love him. I listened to her, and then I listened to him, and felt that love. What Johnny did that night was one of the most indelible blues or rock shows I've ever seen—white-hot music under cool blue spots. As Johnny roared through his Muddy Waters-gone-to-Texas show, he got off what are still some of the most stinging slide riffs ever played in my presence. And though he may have slowed the pace a time or two, the band never stopped rockin'. Not for a minute.

Like so many of the greatest players of the Sixties (Dylan, Hendrix, Bloomfield, Clapton), Johnny Winter did not make much distinction between the blues and rock 'n' roll. That's why what you get here is as much classic rock—including Chuck Berry's "Johnny B. Goode" and perhaps the best version of Dylan's "Highway 61 Revisited" ever put on tape—as classic blues. What makes these records blues are the long, elastic lines Winter's guitar strings out, the undercurrent of sadness that balances the exuberance, the structure and the origin of some of the songs ("Messin' With The Kid" from Junior Wells, "Rollin' and Tumblin'" from Muddy Waters, "Rock Me Baby" from B. B. King). What makes them rock is the relentlessly attacking sheets of notes, the sheer physical exuberance that Johnny pours into the music, the refusal to bend to the pain they express, and the sheer pace and force, which don’t lift for a second, even on tracks as downhearted as "Too Much Seconal."

All blues musicians are essentially artists in pursuit of some fundamental truths about themselves and the people around them—about the human condition as they have known it. The music is about exploring as deep inside yourself as you can stand to go, and learning how you're connected to everyone you've ever encountered; about individual expression standing on the shoulders of all that has come before it. For Johnny Winter, that has been a lifelong task—from his first bands in Texas to the big-time rock 'n' roll career he had when he made the first of these records, to his great work with Muddy Waters, and his departure for a territory that still engages him, out there on the road somewhere, maybe in your vicinity as this new collection spins. He is a true bluesman.

But he has also never lost his rock 'n' roll heart: For Johnny, that great Chuck Berry story about the country boy who carried his guitar in a gunny sack and strummed to the rhythm of the locomotive wheels is his own story. Yet, what called to him was finally not just his name in lights, but the far more enduring sound of the blues itself. No matter what anyone imagines, he's the real thing, and as such must be heard to be believed and understood. The grace note is this: Everyone who listens up is amply rewarded. As a scoffing skeptic who became a fan, I'm living proof.

Dave Marsh

May 1997