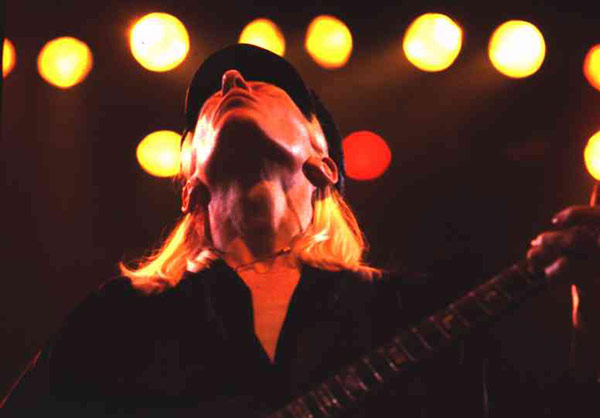

On any scorecard, Johnny Winter sits in the very select group of the most important and influential guitarists in the history of rock and blues, right alongside superheroes like Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, Albert King, and Jimmy Page. With intense burning, virtuoso guitar playing and bad-to-the-bone, gut-busy singing, Johnny stands as the archetype for motor-mouthed blues freaks of all about. Ironically, he's remained at the forefront of the guitar playing scene for almost a quarter of a century, and as we see from 1992, his staying power and staying impressive as ever as evidenced by his latest release, Let Me In (Pointblank/Charisma). The spirit, strength and beauty of the blues takes off full scale in Johnny Winter — he's the best, better example of blues power on the face of this earth.

Johnny Winter was born on February 23, 1944, in Leland, Mississippi yet he grew up in nearby Beaumont, Texas. Inspired by his father, who played saxophone and banjo and was a fan of big band music, Johnny’s first instrument was a clarinet. When he was 11, his father also sent him to the church choir and to barbershop quartet school, and Johnny and younger brother Edgar sang in competitions with the choir. By the second grade, other private teachers forced Johnny off the classical route and into rock experience, he says flatly, “guitar only or hell.” His first exposure to the blues, he heard on the airwaves of the 50’s, on stations like WLAC, KWHK, XTRA &, KJET, included Muddy Waters, Elvis and B.B. King. His first instrument was a ukulele, which he started to play around age 11 or 12.

Says Johnny, “hearing Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters on the radio was like the body organs coming out of the radio – that’s when I decided blues was it. It was inside of me, same kind of stuff I was liking. For years, blues was always thought of as just ‘nigger music’, but it was my kind of music. I was ready to dedicate my life to it.”

At 14, Johnny recruited Edgar for his first band, Johnny and the Jammers, releasing a single, “School Day Blues” / “You Know I Love You,” on Dart Records in 1959, and in the early sixties, he recorded singles for other regional labels. In '64, he cut the Atlantic-licensed “Eternally,” which became a hit in the Texas-Louisiana area, and he began gigging rock ‘n’ roll shows and touring under the band names It and then the Black Plague. In '68, moving from Houston to a grungy pad, as he later termed his flat, Johnny tried with Tommy Shannon on bass (later to join Stevie Ray Vaughan) and Uncle John “Red” Turner on drums; this group became the house band at the Austin club the Vulcan Gas Company. A rising star on the Texas rock and blues circuit with the attention of Steve Paul, manager of the legendary New York City nightclub the Scene, Johnny recorded his first album (dubbed as “Spiritual Godfather” or “Organic Advisor”) for the Texas label, Sonobeat. He signed a lucrative recording contract with CBS and recorded his second eponymous album in 1969, which catapulted him into the spotlight with major praise. His blistering performances were already legendary by the time Johnny was stepping in the effort to get signed. Johnny’s subsequent Columbia releases – Johnny Winter (’69), Second Winter (’69), Johnny Winter And (’70), Johnny Winter And Live (’71) – all took classic blues to dizzying heights.

After drug addiction and reformed in '73, Johnny released Still Alive and Well (’73) and Saints and Sinners (’74) while playing with Muddy Waters, recording his breakthrough blues album Hard Again in '77. Later, Johnny released Nothin’ But the Blues (’77), White Hot and Blue (’78), and Raisin’ Cain (’80) and by then, he had signed with Alligator and released three albums for them, including Guitar Slinger in '84, before moving to MCA, Voyager. All the while, Johnny toured and by 1991, he hooked up again with brother Edgar to record Live in '79 and King Bee in '80. Throughout this period, his guitar playing remained as intense as ever, known for both his rip-roaring slide and his fiery single-string leads, with blistering solos making him one of the most celebrated and admired guitarists in rock and blues history.

Your new record, "Let Me In", sounds great.

I’m pretty happy with the way it turned out. I think I listened to this one more than I do a lot of the other ones. I’ve done a couple of tours, and I can keep playing it and still hear things in it that I didn’t remember that I had done. It was a whole lot of fun to make.

There are two tunes that I love because they’re so funny: "Hey You", from this record, and "I’ll Be Me", from "Winter of ’88". That’s a side of your personality that I think is really cool.

I always try to find songs that have a comic side to them. Somebody sent us a tape of "Hey You", and I really didn’t think that we would end up using it. But it just turned out real cool. "I’ll Be Me" was an old Jerry Lee Lewis song. I hadn’t heard it in a long time. The hardest part for me is finding songs, because I don’t write that much on my own, and couldn’t write a whole album. I always end up finding new songs to do and new stuff, and of course, you always end up doing a few old tunes. The many years that I’ve been recording, it’s harder now, coming up with old stuff that I haven’t already done.

I’ve probably seen you about 50 times now, and I’ve always loved your version of "Hideaway". Do you plan on recording it?

Yeah. We might have tried to record that one and just never got a real great track of it. I haven’t done many instrumentals, and I don’t know exactly why, myself, because instrumentals are easier. "Hideaway" is a great song.

I want to ask you about the T-Bone Walker influence on "Blue Mood", from the new record.

Even though he didn’t play an acoustic guitar, when I thought about doing that song that’s what my producer, Dick Shurman said to do. He had this old ’57 Gibson; he said, “Why don’t you just try it on my Gibson.” I said, “Well, I’m not really trying to sound like T-Bone.”

Are you playing the National on that?

Yeah, but it does sound a lot more like Elmore. I think it sounds more like an electric guitar with a lot of distortion, or maybe a cleaner sound like that guitar as much, even if I would have played stuff. Dick was concerned about the tone, but he said he’s always been a big fan of the Elmore James, and he was afraid all his friends would think that he had talked me into doing that one, and it really is one I had been wanting to do for a long time, and had thought about doing, and I think I heard it on the radio while I was there. They had some real good blues stations in Chicago. After I had come home from the studio one night, they played that on the radio and it just made me remember it. I went, “Oh yeah, I’ve been wanting to do that! Let’s give it a try.”

The sound of the National is brighter and more steely sounding than a regular acoustic guitar.

It’s real hot for that slide sound. Real screamin’. I’d like sometime to do a record just of me on slide guitar doing acoustic slide and screaming.

People are talking about your fingers. People say that it’s the left one that is really where the slide tone comes from.

It’s hard. They were always tight. I’d rather have it all hot.

How about the version of "Nickel Blues", from "White Hot & Blue", with just you on piano. You were killing that piano.

I think I had an old Gibson guitar with an old bar.

That track was amazing.

Yeah, I think I didn’t do that often, played the piano. It was too much.

What about when you first got signed to Columbia, back in ’68 or ’69?

It was right at the last of ’68 and the first of ’69, when we finally signed. It was funny because they wanted it. I had just signed up and I played the record. I had gone to England to see that tape that was later pressed by Blue Horizon. We had had Freddy Records earlier, but it hadn’t come out. We were over there for about two weeks, and then we came home for a while, and signed with, I think it was Blue Horizon, an English label. Mike Vernon had wanted to sign me, and they had had a record with Fleetwood Mac, B. B. King, Chicken Shack, Fleetwood Mac. We hadn’t signed a contract, but after waiting for about six months, we decided to go ahead and sign. The next record had a single, and when I signed with Columbia it was already on CBS and we replaced Mike Vernon.

Your first big record was when you first got signed to Columbia, back in ’68 or ’69.

It was a big record for me, too. I came back, talked about this one being one of the records that should have gotten played. All different labels were crazy, and people were calling. At the time after that, I realized that we could make a better deal by signing in the States at that point. Columbia was the label to beat, and we did that.

How do you feel about that recording looking back now?

Now, they have that favorite record. It’s always been fun and we did the record at CBS Studios in those days.

and the studios really weren’t good for blues and rock ’n’ roll. They had a lot of the older guys that had done symphonic music, so that was a little hard, but I’m still pretty happy with the way it turned out. I wish I had known a little bit more about being a producer. That was one of the first records that I didn’t try producing completely on my own. I know I could have made it a better sounding record now.

One thing great about your records is that if you hit a bad note, you come back crushing and make up for it a million times over.

I’ve never been one for taking out all those mistakes. A lot of people make sure they don’t have any mistakes, but if it had a real good feel, and it had one little weird part in it, I’d just go ahead and leave the weird part rather than do it again; nowadays, you could probably just take out the one note. But I like to keep it like a real performance.

Big Walter (“Shakey”) Horton also played on your first record, on “Mean Mistreater.”

He had a thing where he used a glass to get a kind of a strange, weird effect, and it was not what I wanted at all. I had never worked with Walter, and Walter didn’t want to do anything more than once. I think he ended up being the only song that we got out of it, and we should have got four or five tracks as long as we were there, but Walter kept wanting to play with this glass.

On "Second Winter", the sound that you got on “Memory Pain” is unbelievable. It’s a very heavy sound; it’s also a live mix/arrangement. Do you remember anything about what you were using, to make it sound that way?

There are a few tracks on that record where we put the amp in a stairwell to get that live echo, and I’m not sure if that was one of the songs that we did that on or not, but it might have been, ’cause we weren’t getting a natural studio sound. And you’re playing a Firebird on that one too. I think that was the same guitar I used for “Highway 61 Revisited,” on the first CBS record. I had an old Fender Mustang, and I played that on most of the first record, and maybe some on Second Winter. I think I had a Gibson Special—one of those red guitars that they made real popular in the mid-60s that I used a lot for a while, but by the time I did Second Winter, I was playing the Firebird. I also had a doubleneck Les Paul that I used for a while on the road.

How did you feel about the record "Second Winter" when it first came out?

I thought it was a trip to make a three-sided album, but it’s obvious what we did when we didn’t have enough material for the whole four sides though. I wish I had done a few more cuts for that record.

"Bringin’ It All Back Home" was one that Dylan had real good bluesy stuff on. You also did another Dylan tune, "Like a Rolling Stone", on "Raisin’ Cain".

Yep; that’s the only other one I’ve tried. I assume that Dylan got to hear your version of it. I was on the same bill with him, two or three years ago, when we were playing on one of these big festivals that had six or seven stages. I wish I’d known he was there; I’d have tried to hit him up. That would have been fun; if we could’ve done “Highway 61” together. He was always one of my favorite people. I mean, you can’t be my age without loving Bob Dylan.

Your brother, Edgar, plays great piano on “Drown in My Own Tears,” on the "Johnny Winter" album.

Yeah, and he did the horns on that, too, that’s a great song. In Nashville, it’s easy to find country-sounding players that would do any kind of soul. I tried to get a few good horn players, but they didn’t have a real good sound; and I was afraid any people that sounded black. A piano player in the studio had heard us asking for black singers, and he said he knew some sisters that went to the same church as him, and he called them up. We did that and it was called something to do with “white music business. Can you imagine?” He had four black singers on that.

What are your favorite records that you’ve made?

Usually my favorite ones are when I do something for the first time, like the Imperial record and the first CBS record were two of my favorites, and then "Still Alive and Well", I think, was one of my favorite rock ’n’ roll records I had been after for a couple of years. I had made that feel like a light. I was real happy with my first Alligator record, Guitar Slinger. It was my first blues record. I keep a couple of tracks for several weeks and think about what I’m gonna do. When you’re making a record every year for 10 years, it’s kind of easy to keep up to the time a little while and have more to say.

What about the first record with the And band, "Johnny Winter And", the studio album?

That was my first hit record sold for me. That’s the one CBS really liked "Still Alive and Well", the most. I like the first and the best out of my records. There was nothing really out of tune, everything sounded like it was on fire and alive. And it still sold the most of the ’70s records.

The things I don’t care about much on "Still Alive and Well", are some of the tunes that didn’t stay fresh by the ’70s by ’74 or ’75. When Muddy cut Hard Again, I remember thinking that we needed to show him off a little more. Nickel Blues on White Hot and Blue had Rick was sitting in his house trying to figure out what to do, and I had just started looking for a new band, and we went into a bunch of material, and it was too bad I did so much of that stuff then and not a lot of blues on the record.

I heard Rick did a six-week thing with Steve Beck, and Hendrix would come out and jam. Were there times when it just didn’t feel like everything was going your way?

I played with Jimi a lot, and I played with Hendrix, but I don’t think that Hendrix and I played together. He was always together all three of us at once. That’s something you listen for on a record. I always thought Hendrix was just on the money. I always wanted to sit back and make sure I wanted to know that Rick wanted him there, but it was his name on the gig. He was a strong guitar player, and what you need to know is really was a rock ’n’ roll hero.

Back in the early ’70s, when you were doing huge arenas, it really was a rock show; for a while you were in the big clubs and smaller venues.

Yeah, I’d fill up a 20,000-seat place by myself, and we’d do everything there as long as it was an arena, we could have a real good gig going whether for one show. If you were gonna play in clubs for a few weeks and wanted to have that magic energy and be good to people, because people were working so hard.

You know a big record company will only let you slide for a year, rather than let you do a single note, to have the magic touch. It’s easy to go to the arena shows and all the big gigs that play the big concerts, but the concerts you reach there will not be like the others much at all, but the ones that you do reach people, and play a few old songs, and people will always do what they wanna hear or not.

It’s really hard to let the blues float by. I really love the blues more than people think, and that’s a real good step to keep playing, but it’s the same kind of blues now like it was when I started out. Now there may not be as many blues artists because there are more big pop heroes out there. Sometimes people get in my way. They want to let me be whoever I am now. People like to be at the big arena shows. They don’t let me make it any less of a blues show because it’s not like the big gigs; it’s a lot smaller.