While tunes like “Close to Me,” with its drum-machine handclaps, and “Show Me,” with its pop hooks and harmonies, may not sit too well with blues purists, Johnny’s inimitable slide playing on the vicious “Lightning” and “Stranger Blues” should appease them, not to mention his energized blues riffing on the two boogie offerings, “Looking for Trouble” and “Ain’t That Just Like a Woman.”

The Winter of ‘88 —handclaps, pop hooks and all—no doubt bound to land some new fans for the forty-four-year-old native of Leland, Mississippi. Winter, who grew up in Beaumont, Texas, has for the last twenty years made his home in New York City. Perhaps some of these newly initiated Winter fans will be intrigued enough by The Winter of ‘88 to seek out his great early albums, like the hard-rocking Still Alive And Well , the no-frills trio album The Progressive Blues Experiment (recorded live at The Vulcan Gas Company nightclub in Austin, Texas in 1967) or the great debut on CBS, Johnny Winter , featuring Willie Dixon, Shakey Horton, lots of pure Delta National steel playing and a heart-wrenching gospel rendition of “I’ll Drown In My Own Tears.” Johnny’s canon consists of twenty LPs, including the four he produced and played on for Muddy Waters— Hard Again (1977), I’m Ready (1978), 1979’s Muddy “Mississippi” Waters (all three Grammy Award-winners), and 1980’s King Bee . This number does not include the various Winter bootlegs floating around, such as the notorious Sky High Jam at The Scene in New York with Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison, which Johnny claims not to have played on.

The truly ambitious Winterite can try and track down some of the obscure but noteworthy singles Johnny cut down in Texas for

Ken Ritter’s KRCO label

,

Floyd Swallow’s Jin label

and Huey Meaux’s Pacemaker label. Some of these sessions were recorded under pseudonyms like Texas Guitar Slim, or under band names like Black Plague, Johnny & The Jammers and The Crystaliers.

The road is long from Beaumont to the Big Apple. As Johnny puts it, “I’ve had people tell me that the blues greats on their nerves, that they can’t stand to listen to it for more than a few minutes. But it just makes me feel so good; that’s the reason I know I’ll be playing it till I die.”

Welcome to Johnny in the background photographer Bob Seidemann. The Winter of ‘88 was blaring in the background while the vodka and scotch flowed freely. I brought along a copy of Johnny And Edgar Together , the 1977 rock ’n’ roll album with the striking Richard Avedon cover photo and the collage of nostalgic, hand-tinted family snapshots on the inner sleeve, depicting siblings Johnny and Edgar in innocent days, as youngsters growing up in Beaumont.

GUITAR WORLD: Aside from these great pictures of you and Edgar as kids, this album features covers of tunes associated with Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, and even a version of the Righteous Brothers’ hit, “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’.” What did this project represent for you?

JOHNNY WINTER: That was just a lot of fun ... just a lot of old rock ’n’ roll songs that we had done together over the years in clubs. I guess it pretty much represents what we have in common, musically.

GW: And what are your differences?

WINTER: Well, I tend to like things that are kinda out or left field...things that are pretty raw and spontaneous. I think that’s the big difference between me and Edgar: he enjoys playing with a lot of musicians and having things written out, where everybody knows what everybody else is gonna play. And he, of course, would rather be the person to write it all out, telling everybody what to play. I enjoy playing with a small group where you don’t know what’s coming. Drums, bass, guitar, and maybe a keyboard—that’s really the way I like it. You just count it off and if it’s a good group, the guys just fall in behind you. It’s real important that it’s spontaneous, where the same song might be different every night you play it, so it doesn’t get boring. But if you have five or six horns and a couple of rhythm instruments, which is how Edgar prefers to work, you really have to tell everybody what’s going on.

GW: I know you two have had disagreements about the merits of certain horn players.

WINTER: Well, I’d play him stuff by John Lee Hooker and Lightnin’ Hopkins and he would hate it, just because they weren’t in perfect tune and they would change wrong, like on eleven or fifteen. And that just drove him crazy. But I always loved that. He’d play me stuff by John Coltrane and Art Blakey and all the jazz guys and I’d play him John Lee and Lightnin’ again. We definitely had Ray Charles in common, and James Brown and Little Richard. But I guess we really parted company when he started playing sax and got into horn arrangements. He loved big horn sections, where the parts are worked out clearly ahead of time, and I didn’t like that.

GW: When you get into jazz, you’re dealing with advanced theory and harmony. But if you go farther out—Ornette Coleman or Archie Shepp—you come right back to the blues.

WINTER: That’s what I always thought. I always liked Ornette Coleman for that reason. He was the guy who played that plastic sax, wasn’t he? He’d just do that super far-out strange stuff, and to me, it was the same thing as John Lee Hooker. John Lee can’t tell people where he’s going, ’cause he don’t know himself. But John Lee’s stuff is just as weird as some of the jazz avant garde, to me. As little kids, Edgar and I used to have these big fights about, “Is Lightnin’ Hopkins better than Ornette Coleman?” and I figured, being bigger, I could beat some sense into his head. If you look at some of those snapshots on the inside cover of Johnny And Edgar Together , you’ll notice that I’m hitting him in at least a few of the shots... hitting him in the head with a block in this picture. Slapping his head in that one.

GW: That’s what little brothers are for. I’m sure Jimmy Vaughan was beating on Stevie Ray when they were growing up.

WINTER: Yeah, they were probably slapping each other around, too. Just like me and Edgar. So I guess that pretty much sums up the differences in our personalities. He would rather know exactly what’s going on, with everybody playing something perfectly. I’d rather just count it off and see what happens. It’s funny—now I like to keep everything as spontaneous as possible in the studio. But if you listen to my records, especially back in the Columbia days, they sound very tight, especially on the overdubs. People say it’s hard to believe that I like to keep everything loose because my records are so tight. But they don’t realise how much we went back over that stuff in the studio to make it sound right. We’d take a tune that sounded really loose and spontaneous, and then we’d go back and do the whole thing over again. Even though it sounds natural, a lot of work went into it, and it really didn’t take shape until we did all that.”

...vertised in the paper. You had to know about them. But at some point, he started doing big rock venues and outdoor festivals, and the audience started getting mixed.

WINTER: And once that happened, it made a big difference. They started playing a lot more guitar as soon as they got the white kids coming out. Before, Muddy didn’t play any guitar at all, and he would do his vocals with the guitar hanging around his neck. He’d do the guitar leads, but he didn’t answer his singing the way he does now. When they were playing for black people, a lot of those guys felt that it was cooler to have somebody else play their guitar parts for them so they could just sit there and look sexy and mess around with the mike. Once they made it with white kids, the guitar became prominent. And it made a big difference for me, because I had always thought of myself as a singer who backed himself up with guitar. I didn’t really think of myself as a guitar player, but once I realized that people were thinking of me more as a guitar player than a singer, I gradually changed in my head the way I thought of myself. I began concentrating more on the guitar from then on.

GW: People got very guitar-conscious by the late sixties.

WINTER: They sure did. And hungry for the blues. It was a great time for music and I just saw it getting better. I couldn’t imagine it slackening off at that point. You really couldn’t see an end to it. Bloomfield and Elvin Bishop and Steve Miller were all doing their thing. There was Jimi Hendrix, really doing exactly what I had always wanted to hear somebody do. And it was all on the radio. It was blues everywhere. In fact, I guess so much blues was happening during the late sixties that people just overdosed on it. Because by ’70–’71, nobody wanted to hear it.

GW: Which was right around the time you formed your Johnny Winter Band with Rick Derringer...a heavier, rock-oriented approach to the blues.

WINTER: Yeah, that was closer to heavy metal, I guess. But it still had those blue notes. That’s what’s important to me. No matter what kind of a beat you put to it, it’s still those blue notes that make me feel good when I hear ‘em. To me, “Johnny B. Goode” is a blues song. So I really hate to draw that line between blues, rhythm and blues and rock ’n’ roll. I grew up playing everything. You had to be versatile in Texas bars, because everybody wanted to hear a different thing. So I got really freaked out, once I had “made it.” Before that, everybody wanted you to play everything. Once you made it, they wanted to figure out which category to put you in, and they’d never let you do anything that was out of the ordinary. You were supposed to be either a blues player or a rock player or a country player or a jazz player. And I think that’s what really hurt Edgar, being able to do so many different styles of music well. People just kinda quit buying his records because they didn’t know if it was gonna be jazz, rock, or funk next. And that’s really crazy. If you can play several different things, why shouldn’t you?

GW: You even did a swinging jazz tune on Second Winter : “I Hate Everybody,” with Edgar playing Hammond B-3 like Jimmy McGriff and you playing slick bebop licks like Gatemouth Brown.

WINTER: Yeah, that was kinda what we were trying to do on that tune. That album was an attempt at putting Edgar into the music scene by trying to figure out what stuff we could do that would suit both of us. That’s why we called it Second Winter . It was the second winter we’d been up in New York, and Edgar was the second brother. And it was kinda time to do stuff that wouldn’t be too out of the ordinary for me, but where we could also sneak Edgar in there and let people know who he was. But really, that song was just a blues. There’s so many kinds of blues, and I’ve done them all over my career. I guess my favorite kind of blues, really, is probably the Chicago stuff. Some people feel the blues is a limiting form of music. I don’t feel that way, but since there’s not that many chords in blues, it’s always better to play as many styles of blues as possible, but whatever the style—big band, Delta, Chicago, Louisiana—as long as it has blue notes in there, I’ll always get off on playing it.

GW: You have a formidable slide technique. Who have been your slide heroes?

WINTER: Robert Johnson was really the slide guy. He was so much better than everybody else, that he is definitely the guy to try and imitate. Muddy’s were, too. I learned a lot from him. I’d listen to Muddy and it sounded like somebody was playing a steel guitar and a regular guitar together. You could hear him fretting the notes and then start sliding. I eventually discovered, just by listening to the records, that he was using open tunings. But it was hard to figure out, at first. It was an instrument everybody knew about.

GW: You just finished your three-year relationship with Alligator Records. How do you feel about that period, and how does your new album differ from the direction you took on those albums?

WINTER: I loved those records. They all felt good, and I got to play every kind of blues you can imagine. But there really wasn’t any place left to go. I felt that those three records were really everything that I had to say in that direction at that time. And it was real hard to get away from that, because I kept saying, “I don’t wanna get away from the blues, but I’d like to be able to do something that would have a chance at airplay.” And when you start talking...

...about airplay, you have to figure, “Now, how far do I wanna go in that direction?” It’s always real hard to figure out whether you should go further than you really want to. But on this new record, I was pretty careful. I felt that every song had enough blues in it to make me feel good. Listening to it, I didn’t think that I had sold out to whatever powers that be. I felt that it was still completely along the lines of what I’ve been doing all along. But honestly, I don’t have the faintest idea of what’s commercial today and what isn’t. The new album really isn’t much different from the last three Alligator records, but we did hope that there was stuff on there that the radio people could get into. That’s always hard to tell, though, when you try to play a kind of music that isn’t really well known and you’re trying to get it out there for kids. I guess they’ve heard Robert Cray and Stevie Ray Vaughan and The Fabulous Thunderbirds, so they might pick up on my new record. But the kids who are buying records today aren’t familiar with my early stuff, so it’s like trying to win over a whole new audience.

GW: What’s the story about that bootleg album with you and Hendrix?

WINTER: That wasn’t me on it. As far as I can remember, I played that record and I don’t think it’s me on it. There were a lot of strange things on there—Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin. I remember when Jimi and Jim Morrison, so I know it wasn’t me playing. I did jam a lot with Jimi at The Scene. My manager at the time, Steve Paul, had that club and it was a great place. Everybody would hang out there: Hendrix, The Rolling Stones, Janis Joplin. It was just a little basement place in the worst part of town. I didn’t hold more than two hundred people. I heard some of the greatest jams there. Some of the worst, too. But there is one thing that Jimi and I did there that I heard somewhere. It was “The Things That I Used to Do,” the Jimmy Reed song. I’m playing slide guitar with Jimi on that. That’s the only thing I’ve heard that is definitely me and Jimi together.

GW: How did you feel about all the hype surrounding your CBS debut in 1968?

WINTER: It was really strange. When that Rolling Stone story came out [a feature on great, unsigned Texas musicians, with prominent coverage of the albino guitar slinger], I went from nobody’s even wanting to talk to me in the States to people calling me and offering me all kinds of big advances, just overnight. I didn’t believe it. I knew it wasn’t real. I had been trying to talk to all these record company people for years and they wouldn’t return my calls, and then all of a sudden, overnight, the same people were calling me. And I thought, “What is this? This doesn’t have anything to do with me being good.” You know, it just didn’t make any sense. And the further I went on into it, the less sense it made. I really did realize after a while that talent was a very small part of the whole thing. It also made me realize how ridiculous the record business was.

GW: You got hip to the evils of marketing.

WINTER: Yeah, well, at the time I couldn’t imagine being overdone. People would say later on, “Didn’t you think that you got over-marketed or hyped too much?” But you can’t imagine having too much after you never had anything.

GW: Did it change you?

WINTER: It still hasn’t changed my music. I don’t think. But I guess it has changed me. I’m not nearly as innocent and naive about everything now as I was then. In some ways, I wish it hadn’t changed me. I liked the old me better. But you know, you have to be suspicious of people. You come to realize that the whole thing is so ridiculous and so stupid and has so little to do with how good you are as a player. You either have to just laugh it off and decide, “Okay, it’s ridiculous, but I’m gonna keep trying to do it my way.” Or you get mad at it and say, “I’m gonna quit this and do something else.”

GW: But you never quit. You’re still playing essentially what you’ve always been playing since your Beaumont days.

WINTER: Yeah. It hasn’t changed my music. That part of it hasn’t changed a bit.

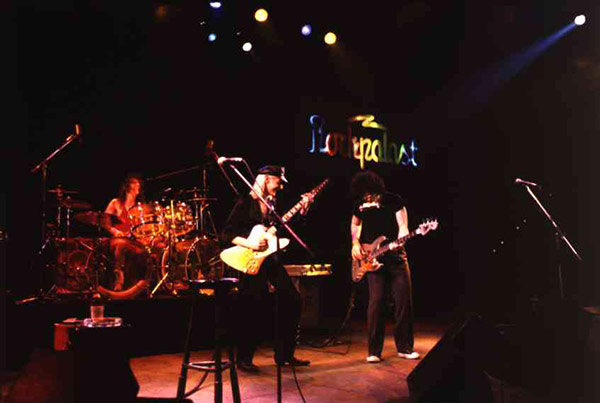

JOHNNY WINTER

...made me a little bit more angry, I guess. And it’s actually made me more aggressive in wanting to stay with the blues and making sure that people are aware of it. The only thing that’s gonna work is just commitment to something. If you just try to follow whatever is happening at the time, you’re just gonna keep being blown around in the wind from one thing to the next. You really have to decide what it is you want to do and not be changed by the ridiculous stuff. And there ain’t that much money in the blues, so the only reason you stay in it is ‘cause you love it. You’re not going to make a fortune out of it, but I really believe it’s important to keep it going.

GW: Is Texas still a stronghold of the blues?

WINTER: Yeah. In fact, it’s gotten a lot better since I left. Right before I left Texas, they didn’t know what blues was and didn’t care, except for the black people who came out to see all the great Texas bluesmen in black clubs. And now, the white kids in Texas think of themselves as blues critics. They just feel like, “We’re from Texas, so we know what the blues is.” That’s just as dumb as the way it was twenty years ago. But at least they care about it now. I’d rather have it the way it is now than the way it was in ’62, where you’d say, “B.B. King,” and everybody would go, “Who’s that? Never heard of him.”

GW: What about the Midwest?

WINTER: I think the Midwest is really one of the best places for the blues. The people in Chicago really think of their town as the home of the blues, what with Alligator Records and all the blues clubs there. They know about the blues ‘cause they suffer through all those harsh winters.

WINTER: Yeah, it’s true. And people seem to be friendlier in a lot of cold places. I really liked Chicago. As soon as you get over to where the weather’s cold.

GW: Man, they’d love you in Siberia.

WINTER: Yeah. I’d love to play Russia. Like B.B. did a few years ago. I really can’t wait to play the Eastern Bloc countries. My Alligator albums just came out in Poland, with Polish liner notes and the whole thing. I really believe that the blues is a universal feeling. You don’t have to understand the words at all to feel it. So I can’t wait to go over there. The rock music that’s going on right now in Russia seems to be more of what I like than what’s going on in America. It’s more like the early Beatles stuff, which I always really liked as a kid. They have more minor chords in their music over there. I guess it kinda reminds you of Russian folk music, but with guitars and big amps.

GW: The blues really transcends cultures. You can hear it in the folk musics of Ireland, India, Bulgaria...

WINTER: Yeah, that’s what really turns me on, trying to find other musics around the world that are similar to the blues. And there really is a lot of stuff. We just played Italy, and I read on the back of a couple of my blues albums over there that there’s a tribe of wandering mountain people in Italy who did something that was equivalent to black blues. And a lot of Arabic music has all these blues notes in it. I don’t know what they call it, but it’s the same feeling all around the world. And I still don’t know what makes some people love it and some people hate it.

GW: There’s some Vietnamese music that has some very emotional note-bending going on. It’s really wailing, but some people say it just sounds like two cats fighting in the alley.

WINTER: Yeah. To me, the emotional music is the stuff that does piss a lot of people off. If it’s got that much emotion in it, it makes people angry. They can’t deal with it.

GW: Same with the blues.

WINTER: Yeah, but I guess all you can do is keep playing it and hope that people are getting off on it. As long as there are fifty or a hundred people that are liking it, that’s great. You don’t have to have twenty thousand people. If there’s a club that’s got a hundred people all really getting off on it, I’d rather play for them than for ten thousand people who are sitting there wondering what they’re doing there.

MARCH 1989 – GUITAR WORLD