August 1987 "Fachblatt Musik Magazin"

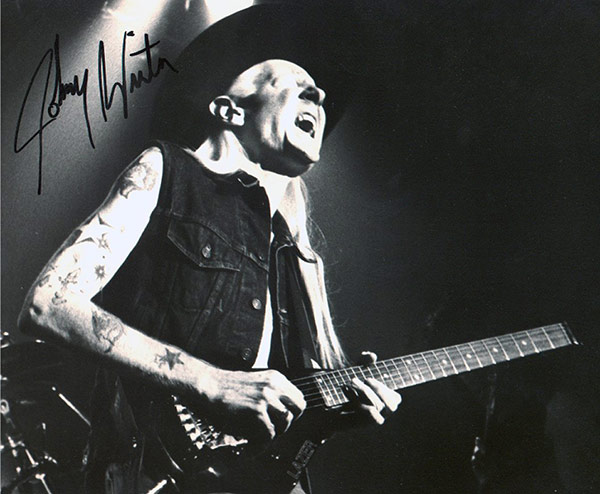

In the German journal "Fachblatt Musik Magazin", August 1987 issue, there's a three-page interview with Johnny Winter. It also includes two photos (with his Matz guitar).

The most fitting statement about one of the most flamboyant figures in the American blues scene could already be read in the US "Rolling Stone" magazine in 1968: "A 130-pound, cross-eyed albino with long, flowing hair, who plays one of the smoothest guitars you’ve ever heard."

By Harold Mac Wonderlea

Well, that's over twenty years ago now, and hardly any of the music journalists at the time would have dreamed that Johnny Winter would still be celebrated on world stages in 1987. Given his drug excesses and his not particularly robust physique, no one gave him much longer to live.

He was already being seen with his Firebird as a permanent member of the "All Star Heaven Band." Despite everything, with a bottle of vodka still on the table, Johnny Winter does exactly what he feels like doing today, and that is the blues—nothing but the blues.

Now in his mid-40s, this exceptional guitarist still easily manages to fill venues, captivating audiences that are a mix of his long-time fans who have aged with him and younger, unburdened blues enthusiasts. Yes, those good old 12-bar blues, mastered masterfully by the albino born in Leland, Mississippi, who was already earning his living as a professional musician at the age of 14 together with his brother Edgar. A prime example of his skills, besides his extensive discography, is his latest LP "Third Degree," featuring pianist Mac "Dr. John" Rebennack and the original rhythm section from the '60s, including "Uncle John" Red Turner (drums) and Tommy Shannon (bass).

In our conversation, Johnny shares some anecdotes from his eventful life, as well as facts about his guitar playing. It starts, however, with him letting me dangle for a few minutes with my first question, as he calmly flips through the "Fachblatt Musik Magazin" that I brought along...

People say you were already making a living with music at age 14. I'd like to know how it all began—how did you get into guitar playing and learn to play?

Well, first let me say "Congratulations" on your magazine, which I’m seeing for the first time today. There's really a lot of information in there. Man, it totally reminds me of my beginnings, seeing the instruments in various US magazines and wanting nothing more than to become a guitarist...

Actually, I was eleven when I got my first guitar. A guy named Luther Nelly sold me the guitar and gave me two or three lessons. Luther was a really good country guitarist, and the first things he showed me were some Chet Atkins tunes. At first, I couldn’t understand how to play those pieces—using your fingers to play the melody and your thumb for the chords and bass lines. Nowadays (he looks at me with large, incredulous eyes, smiling dreamily), you have guys like Stanley Jordan who play with both hands on the fretboard. Terrific! Back then, I listened to a lot of Chet Atkins, and it was hard for me to do two or three things at once with one hand while playing chords with the other. But that’s why I still use a thumb pick instead of a regular pick. I guess I owe that to Luther Nelly. Later, when I got more into the blues, I realized that this style worked well for that too. Besides Luther Nelly, there was another guy named Seymour Drugeon, whose son was my first bassist. Seymour worked with Luther in the same music store, where they had hundreds of guitars. That was in Womack, Jefferson County, and the store was called Jefferson Music Company. Seymour was a jazz-oriented guitarist who played with all those radio orchestras in the '30s and '40s that were always live on CBS or NBC. I had no idea what he was doing with his jazzy chords; I was just fascinated by it. Anyway, Seymour gave me a few lessons when I was 13. Beyond that, I taught myself everything else, especially the blues, by listening to records and trying to play along. And then it really started—Edgar and I were earning money as kids already.

I read somewhere that Les Paul's style had some influence on you...

Yes, through his excellent records. But I didn’t meet him until one day we were both at a Jeff Beck concert. Beck was playing his "Blow by Blow" stuff, and John McLaughlin was also playing that night. Les Paul was sitting a few rows behind me, and during the show, some people went up to him for autographs. Then, all of a sudden, Les Paul came up to me and asked for my autograph. At first, I thought someone was pulling my leg. But I freaked out when I realized who it was. That was our first meeting, and later we met several more times. We even did a little guitar seminar together for the American "Guitar Player" magazine. Although his music is completely different from mine, I learned a lot from him. But in a way, he has influenced nearly every electric guitarist in the world.

But I’ve never seen you play a Les Paul guitar...

I have, but that was many, many years ago. I even had two Les Pauls: a black Fretless Wonder and another Les Paul in SG shape. When they first made SGs, they still called that shape a Les Paul. Both originally had three pickups, but I always removed the middle one because it bored me. I always preferred the sound of the neck and bridge pickups together rather than that stupid middle pickup. I actually played those guitars for quite a long time. It was a completely different story with Fender—I love the typical Fender sound, but I’ve never been able to get along with a Fender. I’ve never played a Fender as well as a Gibson. Nowadays, I play Firebirds, which I find tend to sound more like a Stratocaster.

I’m surprised you’ve been seen playing a headless Lazer guitar so much lately while still maintaining your traditional style.

Mark Erlewine, who has made instruments for ZZ Top, among others, gave me a few guitars, including that Lazer. He charged me twice as much as the damn thing was worth (laughs). And then he had the nerve to ask if I’d endorse it! Seriously, I liked the guitar because it was so small, and you could play it in airplanes or buses, where it’s cramped. At first, I never thought of using it live, but when I was recording "Guitar Slinger," after a string broke on my Firebird, I realized I’d never heard the Lazer through an amp before. So I plugged it in, and everyone in the studio was amazed—the sound was "just great!" I didn’t need the Firebird for the rest of the album.

Sure, there are a few things about it that bother me—it’s really a cheap guitar. First, the cable always fell out of the jack, and I would’ve liked a second pickup since I’ve always liked the sound of the neck pickup. We fixed the most important issues, so now the Lazer can be played on stage, though it still has the same single pickup. For slide stuff, the guitar is too bright, so I use the Firebird for that. Honestly, I wouldn’t advertise the Lazer—it’s a cheap piece of junk, but I play it because I’ve gotten used to it.

Didn’t it feel weird to suddenly be playing such an unusual guitar all the time?

No, not at all—the only strange thing was that it wasn’t strange. Somehow, I could play well on it from the beginning, almost easier than on most of my other guitars. What bothered me was the fact that it only had that one bridge pickup, since I was used to playing the neck pickup on my other guitars. I almost never used the treble pickup, but now it’s the only one this guitar has. We moved the pickup slightly toward the middle, so it’s kind of a compromise now. A few days ago, a guy from Germany gave me a guitar—a "Matz," which I like a lot, with Texas inlays. This guy is a violin maker and made the guitar for me—a beautiful piece.

And you only use the Firebirds for slide now?

Yeah, I still love the Firebirds, but I never fully liked them as regular guitars—they weren’t what I was looking for. But they’re just perfect for slide stuff.

How about high-end guitars like Volley Arts or Paul Reed Smith?

When I'm at home in New York and have time, I spend a lot of time with guitars and try out many different things. I don't know Paul Reed Smith yet. What is that? (Coincidentally, I have the FB 1/87 issue in my case and show him a picture of the PRS guitar, to which Johnny immediately becomes excited.)

Oh yeah, I’ve seen it before, but never played it. What’s special about it?

It’s kind of a high-quality cross between a Les Paul and a Strat.

Man, that's exactly what I'm looking for. I don’t want a guitar with all sorts of unnecessary gadgets. It looks really good, I bet it’s from California. (After I briefly explain the wiring to him, nothing can stop him. He’s practically flipping out and is determined to check out one of these guitars in America immediately.)

It’s ideal with the 5-position switch. Who needs a traditional tone knob nowadays? I will check it out!

You mentioned earlier that you’ve never really gotten along with Fender guitars. What’s the reason for that?

Really, I love the Fender sound, but I just can’t play them. I think you have to hit the strings harder to get a decent amount of punch. With a Gibson, I manage much better. If I play a Fender like a Gibson, nothing happens—the punch is gone, and the tone disappears immediately. You know, I love that brilliant sound that people like Buddy Guy play. Also, I never got along with those one-piece maple necks, not to mention the tuning problems, especially when using the tremolo. There are a lot of things about Fender guitars that bother me—I really can’t play them. Once, I stuck with it for six months—but then I gave the guitar away again, it just wasn’t working.

On "3rd Degree," you make a statement that, at the request of many friends, you're finally playing acoustic stuff again. Was it really that hard to play on those “trash cans with wire on them,” as you call Nationals?

It’s doable. I had to practice really hard because those metal things just don’t play like an electric guitar. I had two different Nationals, but it’s a tough job. The strings are set so high that you could slide a pack of cigarettes underneath them, but for acoustic slide stuff, there’s hardly anything better. The one I used for slide stuff, I’ve had for over 20 years, and I bought the other one about 15 years ago in Nashville. With that one, the strings are set so close to the fretboard that it’s impossible to play slide on it. It's a hard job.

Are you still using your Music Man amps?

Yes, the main reason I've been using Music Man amps for years is that they sound just like my old Fender Super amps, which I no longer take on tour. Those and the old Fender Bassman amps are my favorite amplifiers. I mainly use the Music Man with the 4x10" speakers.

I saw you on stage with just a small effects pedal. What was that?

For years, I used an MXR Phase Shifter. During the production of the last LP, one of the musicians had a chorus pedal, and I’d been thinking for a while about trying out a chorus effect. You know, walking around New York and going into various music stores usually annoys me because people come up, hand me a guitar, plug me into a Marshall stack, crank it up, and expect Johnny Winter to shred some heavy metal. I’m not really into that, so I don’t go to music stores often. I have a friend who owns a store, and he lets me try things out when the shop is closed. Well, with the chorus pedal, it was even easier. The guy had one, I tried it out, liked the effect, and I’ve been using it ever since. I never used to like effects at all, but when the MXR units came out, I thought they were pretty good and I’ve never had any problems with them.

What do you think about developments like connecting guitars to MIDI devices through a converter to create entirely new, synthetic sounds?

I think it's a great thing, really. It’s a whole different world and has nothing to do with what I do. I find it interesting, especially when other people do it. My brother (Edgar), who’s very knowledgeable in that area, told me years ago that it would soon be possible to connect guitars to all that stuff and create entirely new sounds. I’m an old blues guitarist who doesn’t care much about those things, but I do think you can do some very interesting stuff with it. However, I prefer to do things that give me a good feeling—I don’t want to sound like everyone else.

What are the chances that you and your brother might collaborate on something high-tech like that?

Yeah, I’m almost sure that at some point in the future we’ll do something along those lines. Right now, Edgar is working with Leon Russell, which is an interesting combination. My brother and I work together from time to time, and we recently talked about the idea of maybe doing a European tour together next summer. Our musical styles are so different that we can’t work together continuously or for too long. We could make an album and do a short tour, but that would be it. Edgar isn’t a big blues fan, and I can’t play the kind of jazz he’s into. He always wants to do everything perfectly—he’s a real perfectionist, while I’m more about the feeling. We’re completely different types, which is why we don’t work together often.

Let’s get back to your recent activities. You also co-produce your albums with other producers, like Dick Shurman. Bruce Iglauer is listed as Executive Producer. How does that work in the studio, and who has the final say when it comes to key decisions?

That’s been a problem. Bruce often had the final say (laughs). When there are three producers working on something, each one wants to give their input, so that everyone’s happy. And that’s the problem. Sometimes we’d get on each other’s nerves when I wanted a certain drum sound, but Bruce had completely different ideas. In the end, we had to settle for compromises, so that everyone could at least somewhat agree on the drum sound. That’s just one example, but that’s how it goes. After some discussions, we’ve now agreed that Bruce will focus more on the business side, which he’s really good at, while Dick and I handle the technical production side because we complement each other well and work optimally together. When Bruce gets involved in the production itself, conflicting opinions clash, and it can lead to some tense situations.

Still, "3rd Degree" turned out to be a very lively, fresh album.

I agree. It’s what we tried to achieve with the two previous albums ("Guitar Slinger," "Serious Business") but didn’t quite manage. "Guitar Slinger" was nice, "Serious Business" was already a step in the right direction. Overall, I enjoy working with Alligator Records because all the people who are into blues in America, both musicians and listeners, know the label.

The only problem is when you want to get the music on the radio because not much gets played. In the '60s, blues was underground music, and although it’s not called that anymore, its status within the music scene hasn’t changed much. What I don’t like about the whole situation is the fact that there are probably a lot of people out there who would enjoy our music, but they have little chance of discovering it because the marketing industry has hardly any room for genuine blues, and people aren’t exposed to it in the media. Even when I was with a major record company, they didn’t pay much attention to it. They have thousands of promotion people running around, flooding the stations with the latest products, many of which quickly disappear into oblivion. A small blues label like Alligator has it much harder because there’s not much money for such actions. Instead of buying ads in pop magazines, Alligator tries to get interviews with the artists on the label.

Well, it was my wish to chat with you. What are your future plans? Any concrete plans?

Oh, I don’t know. I really don’t. We’ll head back to New York and see what’s going on there. I know there are some TV appearances planned, and of course, we want to get the album more attention. But one thing I know for sure: I’ll keep playing the blues.

FACHBLATT MUSIK MAGAZIN_