WE'RE CRUISIN' at a steady 65 through the endless conurbation that connects Dallas to Fort Worth, past a clutter of A-frame hamburger stands and drive-in movie lots where the images of long forgotten B-movies flicker in silence on the huge curved screens.

With the air conditioner on full we pass waffle shops, the Bonanza Sirloin Pit, Taco Bell with its unknown soldier flame, and MacDonalds.

KRLD-Dallas pumps country at us past The Last Chance Motel, with "Howdy Stranger" written on the entrance, and even past The Soul's Harbor Church with its huge electric cross reclining on the roof – stark electric Jesus illuminating the vast empty Texas night.

We are going to interview Johnny Winter in his home state and up to now it hasn't been easy. We caught a glimpse of him after the concert at Dallas University, where we waited near the stage but then a throng of fans were suddenly herded off the premises and the whitest of all the white guys didn't even have time to scrawl a few hasty autographs before his blackened limousine pulled away with us in pursuit.

The limo pulls off the road into the Jack In The Box drive-in and stops at a larger than life-size illuminated plastic figure of a jack-in-a-box in the middle of the parking lot. Johnny orders cheeseburgers, chocolate milk and a bowl of cottage cheese. A disembodied voice from the clown figure checks the order and the limo pulls forward to the service building.

By the time our car reaches the serving hatch there is considerable confusion. The owner of Jack's voice has had several paper plates autographed and, seeing that we are part of the entourage, he gives us free milk shakes and coffee.

"Anyone who's a friend of Johnny's . . ."

One thing is sure: in Texas Johnny Winter is a superstar.

Finally, we pull into the Inn Of Six Flags Motel and settle down to wait until Johnny's manager Teddy thinks it's okay for us to go up. He gives me last minute instructions:

"He hasn't touched drugs for a year. He's off all that. I may give you a signal after 45 minutes to stop. Johnny's very nervous of talking, particularly to the English press – he seems to think they tear him apart."

The signal's a go-ahead and I reach his room indicating that we should interview. But as soon as I walk through the door I realise everything's gonna be all right:

"Man, this is an interview man, all you had to do was to tell me."

Johnny and I sit, one on each bed, facing each other, real close. At a distance of about 18 inches from me he closes his eyes and begins his rap. He has changed, he is relaxed, he even looks happy – a far cry from when I last saw him, just before he went into River Oaks Hospital, New Orleans, to spend nine months recovering from heroin addiction and suicidal depression. He admitted himself – he was not committed . . .

"None of my friends ever get committed, we always just give up. You know when you're nuts. You know when you can handle it and when you can't, and we just say 'Okay world. I give up. Sorry. I can't figure out what I wanna eat, what I wanna wear or what I wanna do and life is jus' too hard so just take care of me until I . . . Don't let me kill myself, just kinda keep me here on ice until everything starts working out'."

"All my good friends, every one of 'em has gone nuts. It's sump'm you just have to do for one reason. I don't know . . . the lifestyle, what you have to do on the road to keep things goin'. . . Those things jus' seem to, uh, drive people outta their minds!"

"But once you go through that it's easier at least to figure out what you shouldn't do to try again. There's no guarantee but at least you do get an idea – usually – sometimes – hopefully – haha!!"

So what's it like when you come out of the whole scene?

"I felt really great, it was a year after when I finally decided. 'Okay, I think I can go ahead and keep on. I wanna keep on doin' this. I don't wanna die. I don't want nothin' weird. Let's just keep on whippin' it out'."

"I really felt good.

"But I've only been really happy for about the last eight months when I started doin' the thing with Muddy. Until then I figured I had no right to expect real happiness and that I would never be really happy – but I didn't wanna die either.

"My whole concept of what I was and what I wanted to do didn't happen. It was real frustratin' to me. When I first started doin' blues I really wanted the thought of that as a blues player and I got so much crap from the purists and the young white people – there was never any problem at all with the old black people who I loved and learned how to play from and played with.

"They always stuck up for me and said great things about me.

"I got so much crap from the media that finally I just stopped, y'know? When I first was startin' to make it in New York I got all these great reviews – but we had a band that should have been compared to hands like Muddy's and Lightnin' Hopkins and Lightnin' Slim and Otis Rush.

"Instead they were comparing me to Cream and Jimi Hendrix and I wasn't tryin' to do that at all! I was playin' straight country blues, not blues rock, whatever you call it. It was country blues and it hurt me real bad because after those first original great reviews people were judging me for a totally different thing.

"See I thought of myself as the best white blues player around. In my own mind I was sure of that. But I never thought of myself as like Jimi Hendrix or Cream. I loved Jimi Hendrix and I loved Cream, but I wasn't tryin' to compete."

"Then the reviews sayin' I was better'n everybody in the world and everything, and I never felt that way, I never thought things like that. But then after those reviews people were lookin' for something totally different when they saw me in person, and it wasn't there, you know? I work in a fillin’ station. I still wanted to play. I loved rock ’n’ roll and do still love rock ’n’ roll but I almost stopped doin’ blues.

"It was like my whole life had been in two pieces until Muddy Waters asked me to do a record, and when that happened I could finally take a sigh of relief and say ‘Oh yeah, everybody understands, everybody’s got it. I’m bein’ accepted for what I wanted all those other eight years.

"Those eight years helped a lot to drive me outta ma’ mind. But after all that terrible stuff, it’s okay again. Man, it’s like taking the best shit you’ve ever taken. It’s GET IT ALL OUT and just CLEAN EVERYTHING OUT, you know? There it is, just finally working, just the way that I was always hopin’ it would.

---

THE ABSOLUTE dedication that Johnny has for Muddy Waters is initially surprising — after all, it’s unusual for a producer to love his artist quite that much — until you remember that working with Muddy Waters was not just a professional job; it totally transformed Johnny’s life, emotionally, musically and financially.

He first met Muddy in Austin, Texas, in 1968 at the Vulcan Gas Company:

“Tommy Shannon, Uncle John and I were playin’. We had a blues trio there and we were doin’ straight blues — not like Muddy’s thing, more the kind of blues that I’m doin’ now. It wasn’t really rock blues, it’s just the difference between, uh, a band of 60-year-old black guys and a band full of 20-year-old white guys. So it was different.

“When Muddy’s band first went on, they kind did a soul thing ‘cause they didn’t know exactly what the young white hippies wanted. They just weren’t too sure so they did their soul set. Then we went on and did a lot of Muddy’s tunes — straight blues, and the audience liked that a lot.

“Muddy was listenin’ to it. Then he came back on and played a great set. He realised ‘these people really do want to hear this kinda stuff’ so he just wiped everybody right on out.”

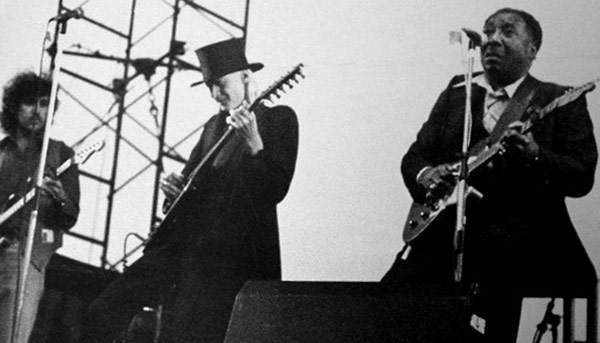

Over the years Johnny and Muddy appeared on the same bill from time to time, did TV shows and sat in with each other.

Muddy’s career, meanwhile, was not going too well. He was not doing well financially even though he’d stayed with Chess for 30 years. And when Chess was sold out, his contract was bought and sold around town like a can of dog food. He felt no-one really cared about him. His records didn’t sound good and he didn’t like his management.

Johnny takes up the story:

"He just said ‘I’ve had enough. I wanna get out of this deal’ and he talked to the people at CBS. They said they didn’t know exactly what to do with him but why didn’t he talk to Steve Paul at Blue Sky because ‘Johnny Winter’s on that label’, and Muddy said, ‘Well, if Johnny Winter’s on that label, d’you think Johnny’d want to produce me?’ and they said, ‘Well, call up and find out.’

“And of course, ha, ha, that was all it took. My manager calls me and said, ‘D’you think you’d have time and wanna produce Muddy Waters?’ Well I couldn’t believe it, you know? It was jus’ somethin’. To me Muddy was one of the really great blues players and he hadn’t gotten the success he deserved. So, ‘Yes, I sure want to do it.’

“Man, I was so scared. I go in now that it’s over but . . . He was the first person I’ve ever produced besides myself — except for Thunderhead’s album and that never even came out — so . . .

“I mean, I just knew if I ever got a chance to sit in with him . . . that was too much to hope for. But actually havin’ him say, ‘Johnny, play guitar on my record, produce it, do whatever you want with it’ was more than I could ever even imagine.

“I was scared because though I thought, ‘I’m the only guy in the world who can make blues records sound like they used to and like they should.’ But there was still that worry back there — ‘Are you sure you can do it?’

“If I bombed out — wow, that would’ve jus’ blown me away."