Johnny Winter Talks to Miles

By this time Johnny was onto his second bottle of Blue Nun, chug-a-lugging it from the bottle. He stripped off his shirt to get even more loose. He was really warming to his subject

"My whole concept was totally different. I wanted to try to make things sound as crappy as we possibly could as far as fidelity and that kinda stuff goes. Like the old people, the old rock 'n' rollers, Carl Perkins, Little Richard, Chuck Berry and the old bluesmen are recorded awful today because, in the old days when it was mono, everything was just all together in a big ball of sound that came right at you and gotcha.

But now you can hear things you'd never hear on a club job. Everything is so separated. You can hear the pick on the strings and the snares on the snare drum. Everything's so clean and so near that those people, to me, have just been recorded terribly.

The only way I could do it was to find an engineer who'd be willin' to help me go back about 25 years.

The guy who's doin' our sound knew hardly anything about blues but he came over to my apartment and I just played him things and said, 'Dave, could you possibly get off on tryin' to do an album which is not a modern version of what things used to be like but really the way things used to be – as much as we can do it with the equipment that's around today?'

And he said, 'Sure, if that's whatcha wanna do, you're nuts but I'll give it a try.' I played him records for two or three days. I don't know anything about the technical part; all I can do is tell an engineer, 'Okay, it sounds too mushy, it sounds too fuzzy, it's too trebly, too bass-y, whatever... I've gotta have a good engineer and it really worked.

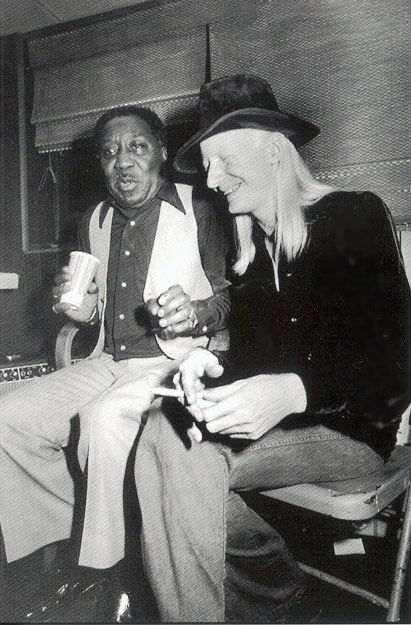

I figure my job with Muddy is not to lead him in a particular direction. It's to find out what would really make Muddy happy. If it didn't have anything to do with recorded sales, money or anything, what would make him the happiest — the musicians, the way we recorded, the time we recorded, all those things. And try to make that happen. I try an' make it 100 per cent comfortable for Muddy.

It's not my job to say, 'Okay Muddy. This is what you oughta be doin'. Muddy has been around a lot longer than I have and he knows what he oughta sound like. I can do that now because we've got money. When he was at Chess he couldn't say, 'Yeah, I'll fly a man from California.' But now he can.

At first I thought I was goin' to just produce. I didn't think I was gonna play my guitar. Then, at the last minute the day Muddy came in, I said, 'You'n Bob is goin' be playin' most of the leads' and he said, 'No you're gonna be playin' leads.' I said, 'Wait a minute. I'm producin'. I can't play an' produce this thing at the same time.' And Muddy said, 'Sure. I thought that was supposed to happen, man. I wouldn't be here if you wouldn't be gonna play on the record.'

So I had to go and play and then go upstairs and analyse the sound we were gettin', and I was real scared that I couldn't be objective. I was afraid, well, that I'd start playin' too much — the excesses of Johnny Winter (which I'd like to say to all blues purists — it's not just excessive, it's great!).

Johnny leaned over to shout the last bit into the tape recorder in case any purists missed it.

I knew that the Johnny Winter style of blues playing would not fit right with Muddy Waters. I had to play Johnny Winter style but Muddy Waters to do it right and it's super hard when you're producing.

Muddy's whole thing is based around his great voice and harp; it's not based around guitar, and there can't be a lot of flashy Johnny Winter stuff goin' on in there. It was hard to do it because I am a Johnny Winter egotist, I'm a total Johnny Winter groupie. But I did it. I really thought of myself as the producer, not as a guitar player. I was just backing up Muddy on guitar."

In keeping with his aim of returning to the sound quality of Muddy's early records, he mixed the record as close as possible to mono.

"I gave 'em just enough stereo so the record company wouldn't tell me to kiss off, whereas if I had my own total way we wouldn't have nuthin' in stereo.

When they were pressin' the Muddy Waters album up, I was down there checkin' things out, and this guy comes up to me and says, 'Hey, ah, you produced this record, right?' 'Well, there's something wrong with it, man. We're not gettin' any kind of separation or stereo at all.'

And I said, 'No, there's nothin' wrong. That's the way it's supposed to be.'

He said, 'Naw, you gonna put this record out this way? I mean, you want me to press this thing up?' and I said, 'Yeah. Whip it out. Press it all up, man.'

He said, 'Well, ah, a lot of people are gonna be angry, they're not gonna like this!'

As soon as this tour is over I'm gonna do Muddy's next album and we're tryin' to get together as many of the old guys that Muddy used to play with. I'm gonna try and play less. We've got Jimmy Rodgers, who used to play guitar with him. He's ready to do it. And I think Big Walter Horton, 'Shakey' Horton's gonna play harp. Maybe we'll get Willie Dixon on bass. These are jus' names we're thinkin' about. We wanna get as many of the original people as possible.

All I got to do is make sure that the rest of the guys I get can still do it. If they're not good now, forget it.

I'm just gonna try an' get the album dirtier, nastier, funkier, and if anything make it sound older."

---

AFTER RECORDING "Hard Again".

Muddy went out on the road for five weeks with Johnny, using the same lineup as on the album. Another dream come true. And being on tour with Muddy gave him a lot of work to do.

"Most of the time he didn't play guitar. But when he did play it was just as good. It seems he wants to do more diversified blues an', well, y'all know what happened to Elmore James, right? — every song started to sound like 'Dust My Broom.' I mean, Elmore is a great bluesman but Muddy has got a little bit more sense and he Here is the transcription of the second image:

---

doesn't want that to happen. So what he tries to do is fit his parts into where they'll just wipe everybody out. He knows he can pick that guitar up and play and everybody'll go nuts.

"When I was workin' with him he would probably play two songs a night and put everything he had into 'em an' they were jus' beautiful and the rest of the time me an' Bob would fill in and play the kinda things he thought Muddy wanted to hear behind himself. He's a smart man. He knows exactly what he's doin'. Muddy don't stumble into nuthin'. He's a real professional."

They came back and, still with the same line-up, went into the same studio and cut Johnny's own album, "Nothing But The Blues", using the same "almost mono" production technique.

Johnny sits back on the bed, a huge Texas smile on his face, eyes blinking fast behind pure white lashes, waving his "Nothing But The Blues" in the air. He looks really happy. It's great to see him this way.

---

I used to live in the same hotel as Johnny Winter in New York, and used to see him crossing the lobby, a tottering drug-swept stick insect held together by a grim joke of management. I used to see him sit outside in Steve Paul's Scene, his old manager, and watch as he played then well because you had to, despite his voice reduced to a terrible anguished croak. Shortly after that, he entered hospital.

It had not been easy for Johnny — or his brother Edgar — to grow up albino in intolerant Texas where the survival of the fittest is still the basic philosophy of life. Johnny managed to survive but doing so gave him a deep personal understanding of the blues.

"Being an albino was fairly weird. Before I got into music the main thing I did was fight people because I couldn't see good enough to play football or baseball, but I could see good enough to fight so I had that down real good.

"By the time I was 14 or 15 I started playin' in bands and, plus, everybody else started gettin' bigger. See, I've been this small since I was 12. I had a good reach and I boxed a lot, so if somebody didn't like me I could just beat the hell out of 'em.

"When everybody else started gettin' bigger I started playin' music, so I was right in the band. If I hadn't played guitar I don't know what I'd have done. By the time I was 15 I was hangin' out in clubs and I totally got outta that school trip.

"After I got too little to fight, what I did instead of football was play material, got hired out to a club and tried to make it with his girlfriend. When I was 18 or 19, that was it. I was still with girls that were 30 and 35. 'Aw, cute lil' Johnny!' You know, you hit the middle-age chicks like havin' little kids, and I was always a little kid."

"You'd be on tour in New York & turn on the charm, being able to get, oh, maybe two or three chicks a week if you were lucky — or one chick a week — to bein' able to get five or ten or 15 a night. Like in Copenhagen was really nice. Wow, we got some great orgies goin' there with no guys an' just me. Wow, I loved that for a while.

"Then that got boring. I got clap 20 times and it jus' got to be a drag. All that glamorous stuff that turns people on at first, like dope and girls and everything, got to be totally boring. I was spending more time in the doctor's office than in the studio. I figured, 'This is crazy' and I just, uh... just stopped! I started takin' dope and went crazy. That's what I did. Yeah!

"So now I don't do much of anything. I won't stay on the road more than six weeks at a time. I couldn't handle it. I love to work and I don't mind going on the road, but I do mind bein' on the road every night.

"I'm always terrified before I go onstage too. The last two hours before I play. When I walk onstage and start playin' it all goes away. But for a coupla hours anything in the world can make me mad. Just the work kinda hard an' I can go nuts."

"I guess part of it is that I really wanna be great — I'll still get off on tryin' to carry the show. Everybody's gotta have off nights. But why should somebody pay seven bucks to see me play one place and hear a great concert and seven bucks another place and not hear a good concert?

"If I feel like I haven't done a great job, I usually go back to my room, get totally drunk and bounce off walls. Every show, every album has gotta be the best."

---

"Another thing about bein' accepted as a producer is that I can stay in New York and work every day and make a good livin' — so I don't have to be on the road. So I can be on the road like a third of the year, and do a Muddy album and a Johnny album every year.

"The thing I really wanna do, of course, is keep on recording as many of the old guys as I can, because a whole lot of the great people are already dead and there are a lot more that are still great, but old. And when you're 67 years old you can't expect to be around for too much longer. A lot of these guys are still playin' great music and nobody's recording it. That's the main thing I want to do but I doubt if I'll ever get the chance to do it."

And finally: "I've always wanted to be successful — not really to be famous, but to be respected for what I did.

"I've always wanted to be able to travel, a decent place to live, decent food, and to be respected.

"I really wanted acceptance. I wanted to make everybody happy and thought everybody'd be pleased and that's impossible. I don't really care anymore if somebody doesn't like the way that I play, they can just go screw themselves. I still want people to like me but I don't want it enough to go out of my way and try to be something that isn't really me anymore."